- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Identification and characterization of flowering genes in kiwifruit: sequence conservation and role in kiwifruit flower development

BMC Plant Biologyvolume11, Article number:72(2011)

Abstract

Background

Flower development in kiwifruit (Actinidiaspp.) is initiated in the first growing season, when undifferentiated primordia are established in latent shoot buds. These primordia can differentiate into flowers in the second growing season, after the winter dormancy period and upon accumulation of adequate winter chilling. Kiwifruit is an important horticultural crop, yet little is known about the molecular regulation of flower development.

Results

To study kiwifruit flower development, nine MADS-box genes were identified and functionally characterized. Protein sequence alignment, phenotypes obtained upon overexpression inArabidopsisand expression patterns suggest that the identified genes are required for floral meristem and floral organ specification. Their role during budbreak and flower development was studied. A spontaneous kiwifruit mutant was utilized to correlate the extended expression domains of these flowering genes with abnormal floral development.

Conclusions

这项研究提供了一个描述得这么花pment in kiwifruit at the molecular level. It has identified markers for flower development, and candidates for manipulation of kiwifruit growth, phase change and time of flowering. The expression in normal and aberrant flowers provided a model for kiwifruit flower development.

Background

在过去的几十年中,猕猴桃(Actinidiaspp.) has developed into an important horticultural crop. The genusActinidiabelongs to the familyActinidiaceae within the Ericales order, contains 76 species originating mainly in China [1] and consists of perennial, climbing or straggling, deciduous plants. All members ofActinidiagenus are functionally dioecious, with male and female flowers carried on different plants, typically at the basal end of the shoot [2]。Female flowers undergo androecial development but lack functional pollen and male flowers cease gynoecial development upon initiation of stigma. The reproductive cycles of kiwifruit commence after a juvenile period required for establishment of flowering competence. In mature kiwifruit plants, growth and flowering are spread over two growing seasons. During the first growing season, a number of phytomers and axillary meristems are initiated in latent shoot buds at the distal end of the shoot, which enter a dormant state and develop into inflorescence-bearing shoots early in the second growing season, at spring budbreak [3–7]。Kiwifruit inflorescences are compound dichasia, but lateral flowers in most female cultivars cease development soon after their initiation and only terminal flowers develop [8]。

Conflicting reports are available on the timing of floral commitment, ranging from the spring of the first growing season [4,5,9] or late summer of the first growing season [10], to the spring of the second growing season, immediately before flower differentiation [11]。In addition, flower development during the second growing season depends on environmental conditions, most importantly winter chilling; insufficient chilling results in unsynchronized budbreak, low flower numbers and subsequent low fruit yields.Actinidiaspecies differ significantly in their timing of budbreak, winter-chilling requirements, lengths and numbers of nodes per shoot, indicating a genetic control of shoot growth and flowering.

Current research on kiwifruit is mainly focused around consumer-driven traits such as fruit flavour and fragrance, appearance, healthful components and convenience [12),但知识的遗传调控growth and development, flowering and sex-determination is very scarce, yet essential to accelerate breeding and aid our understanding of flowering control in kiwifruit and woody perennial species in general.

Molecular and genetic regulation of flower development has been subject to detailed analysis in various plant species. Specification of floral organ identity in model plantsArabidopsisandAntirrhinumhas been explained by the classical ABC model [13,14]。Identity of floral organs is determined by three classes of function, A, B and C, each consisting of one or more genes [15–27]。Further research resulted in the revised ABC(D)E model [28–34]。In addition, the A class geneAPETALA1(AP1), together with other members of theAP1/FUL-like gene family andSEPgene family, have a role in specification of floral meristem identity [35,36]; another A class geneAPETALA2(AP2) is also implicated in the control of floral transition [25], seed size [37] and maintenance of the stem cell niche in the shoot meristem [38]。With the exception ofAP2, all the floral organ identity genes are members of the MADS-box family [reviewed in 39]. They all belong to the plant-specific MIKC type MADS-box genes [40], orthologs from different plant species generally belong to the same MADS-box gene subfamilies [41–50] and their function is well correlated with expression patterns [51]。

In general, the ABC and ABCE models are widely applicable to non-model plants, with a few caveats. Whereas the B, C and E functions are regarded to be broadly conserved, the A function in specification of the perianth is not widely observed and questioned inAntirrhinum[52,53], as well as other plants [54]。In addition, this model fails to explain floral diversity seen within flowering plants, and additional models have been proposed [55–57]。Evolutionary developmental biology of MADS box genes in a range of angiosperms has been instrumental in the development and testing of these models [reviewed in 58] and further broad comparative studies, including normal and aberrant flowers in a range of species, will aid understanding of the mechanisms underlying the variation in angiosperm floral morphology.

The objective of this study was to functionally characterize genes required for development of kiwifruit flowers. Specifically, this study aimed to: (i) identify genes that specify floral meristem and floral organ fates in kiwifruit; (ii) identify if specific expression patterns may have led to the aberrant morphology of some kiwifruit flowers; and (iii) develop molecular markers to monitor kiwifruit floral development. Nine MADS-box genes highly similar to class A, B, C, and E function genes were identified and further characterized using cultivars of the closely related kiwifruit species,A. chinensisandA. deliciosaand anA. deliciosaspontaneous mutant 'Pukekohe dwarf' with an abnormal floral phenotype. We discuss kiwifruit flower development in the light of the existing flowering models.

Results

Identification of kiwifruit candidate genes

Nine non-redundant kiwifruit MADS-box genes were identified on the basis of similarity toArabidopsisfloral MADS-box genes, and namedActinidia FUL-like,FUL,AP3-1,AP3-2,PI,AG,SEP1,SEP3andSEP4(Table1).For some genes, multiple near-identical sequences were recovered reflecting alleles, sequences from different genomes within polyploid genomes or orthologs from different kiwifruit species (Table1).

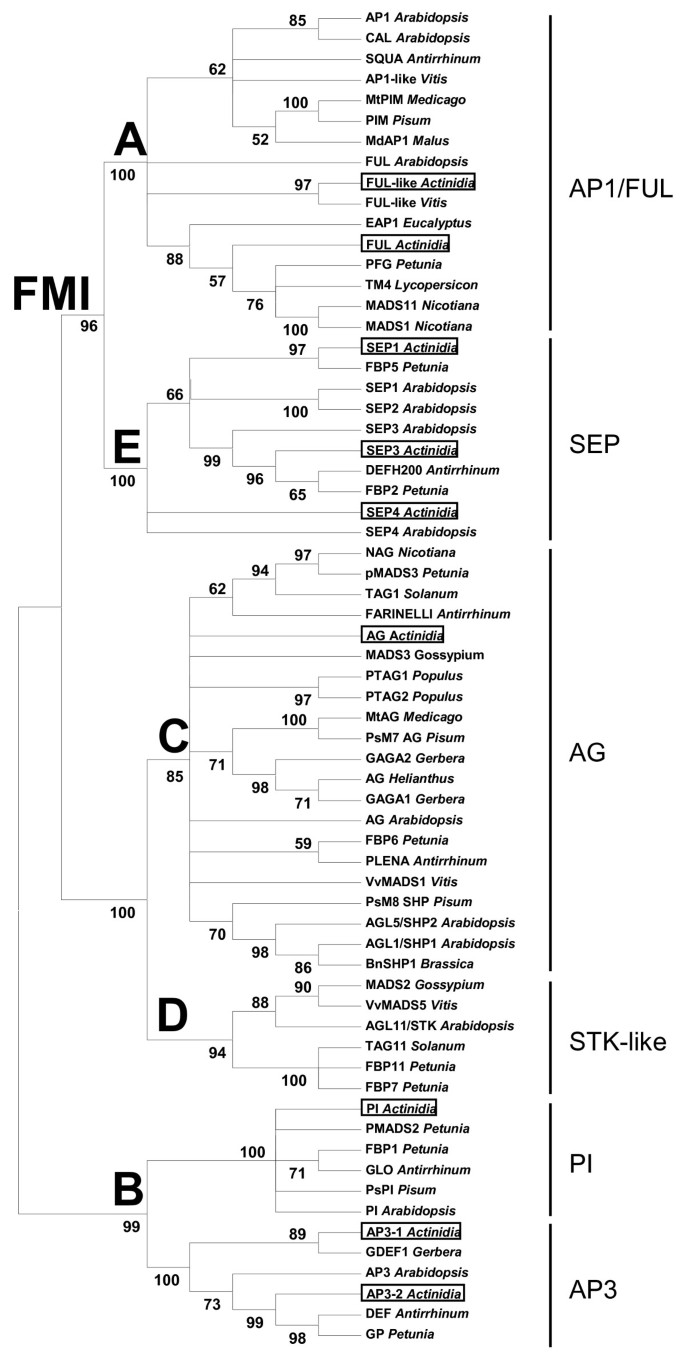

Phylogenetic analysis further confirmed that the identified floral MADS-box genes belong to appropriate MADS-box gene families and subfamilies (Figure1).All the predicted protein sequences of kiwifruit MADS-box genes contain the conserved MIK domains and a variable C-terminal region with conserved C-terminal motifs (Table2).None of the identified MADS-box genes has the carboxyl-terminal CFAT/A farnesylation motif characteristic of euAP1 proteins. The predicted AG protein was clustered in the C lineage of the angiosperm AG subfamily (Figure1), but the C and the D lineages are closely related and often difficult to distinguish. PCR amplification of the genomic DNA identified an intron located in the last codon (Additional file1), which is characteristic of the C but not the D lineage [59]。

Phylogenetic analysis ofActinidiaflowering genes.The MIK regions of MADS-box proteins were aligned using Clustal W (opening = 15, extension = 0.3) in Vector NTI 9.0. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version 3.1 [78], using a minimum evolution phylogeny test and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Gene names shown in rectangles areActinidiagenes identified in this study. Class of function and floral meristem identity function (FMI) are indicated in bold.

Overexrpession phenotypes of kiwifruit flowering genes

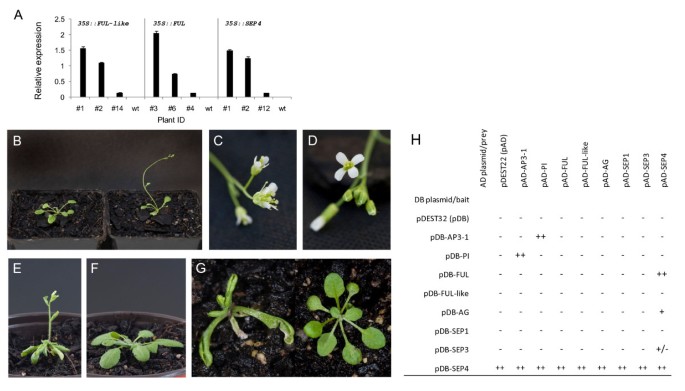

To establish the potential role of identified genes in regulation of flowering, their cDNAs were ectopically expressed in wild typeArabidopsis.Among the minimum of 10 kanamycin-resistant lines per each construct, three or more were chosen for detailed analysis. In general, two of the chosen lines displayed strong phenotypes and one line was chosen that displayed a weak to moderate phenotype (Table3; Figure2A).

Phenotypic analysis of transgenicArabidopsisplants ectopically expressingActinidiaflowering genes.A. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of transgenes in transgenic lines chosen for analysis. The expression of each gene was normalized againstACTIN.Error bars represent SE for three replicate reactions. B. TransgenicArabidopsisplant expressing35S::FUL-like(right) flowered earlier than the wild type plant (left) when grown in short day conditions. C. A compound terminal flower phenotype of35S::FUL-liketransgenicArabidopsis.D. Wild type phenotype of flowers of a transgenicArabidopsisplant expressing35S::FUL.E. TransgenicArabidopsisplant expressing35S::SEP4flowered early in long day conditions and produced smaller curled leaves. F. Wild typeArabidopsisgrown as control for D. G. TransgenicArabidopsisplant expressing35S::AG(left) and grown in short days, flowered earlier than the wild type plant (right), after producing only four curled leaves. H. Protein interactions detected by yeast-two-hybrid assay. Yeast growth, representative of protein interaction, was classified as absent (-), weak (+/-), moderate (+) or strong (++). SEP4 bait (pDB-SEP4) was excluded from analysis due to strong auto-activation.

KiwifruitFUL-like, when over-expressed inArabidopsisCol-1 under the 35S promoter, promoted floral transition both in inductive long-day (LD) conditions and in non-inductive short-day (SD) conditions (Table3; Figure2B).High levels of transgene expression resulted in the terminal flower phenotype (Figure2C).No homeotic transformation of floral whorls was detected in transgenic plants.

KiwifruitFUL, when over-expressed inArabidopsisCol-1 under the 35S promoter, promoted flowering but less efficiently thanFUL-likeand the flowers were indistinguishable from the wild type (Figure2D).The ability of this construct to induce precocious flowering was dependent on day length conditions (Table3).Constitutive over-expression of kiwifruitSEP4also promoted floral transition (Table3; Figure2E-F).In addition, many of the plants had small and curled leaves (Figure2F).Plants grown in short days often reverted to vegetative growth, producing aerial rosettes (data not shown). Constitutive overexpression of kiwifruitSEP3had only a mild effect on the timing of floral transition in inductive LD conditions (data not shown). Ectopic expression of kiwifruitPIandAP3-1produced plants indistinguishable from the wild type (data not shown). Constitutive over-expression of kiwifruitAGresulted in plants with reduced height and curled leaves, which flowered significantly earlier than the wild type in non-inductive SD conditions (Figure2G).These plants displayed loss of inflorescence indeterminacy and homeotic modifications that resembled the phenotype of transgenic plants ectopically expressingArabidopsis AG[60]。

To confirm that the identified kiwifruit genes encode proteins capable of forming complexes between each other as predicted for floral MADS-box genes [28,32], a yeast-two hybrid analysis was performed. It established interactions between B class proteins AP3-1 and PI, as well as FUL and SEP4; weaker interactions were detected between AG and SEP4 and SEP3 and SEP4. No interactions were identified with FUL-like and SEP1 (Figure2H).

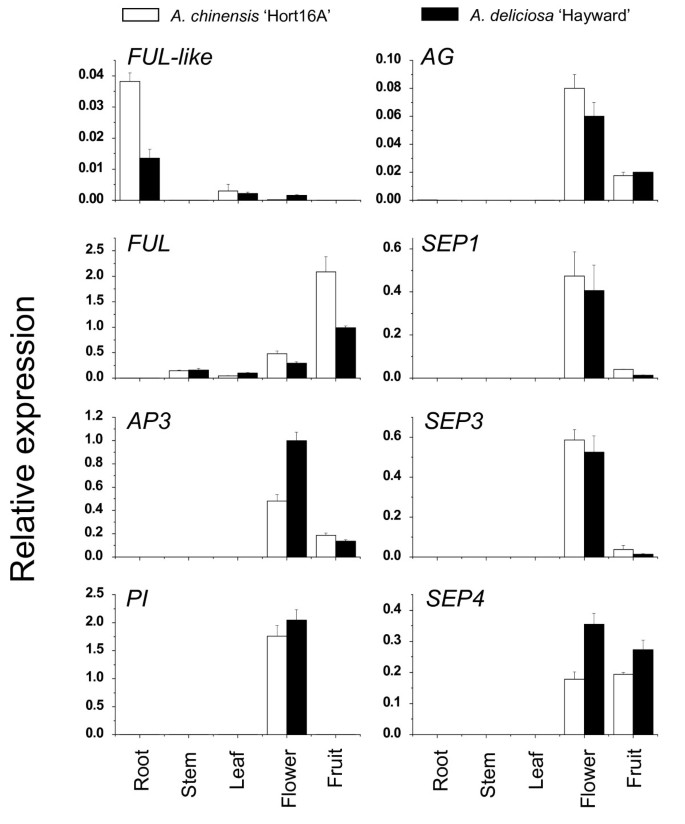

Expression patterns in vegetative and reproductive organs

MADS-box gene functions are well correlated with the expression patterns in a variety of plant species. To establish the role of identified genes in kiwifruit, their expression patterns in various vegetative and reproductive organs was interrogated by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), using two closely related kiwifruit species, a diploidA. chinensisand a hexaploidA. deliciosa, which exhibit differences in fruit characteristics, vine morphology, timing of budbreak and requirement for winter chilling. With the exception ofFUL-like andFUL, expression of kiwifruit flowering genes was confined to flower and fruit tissues of both species chosen for analysis. KiwifruitAP3-1,AG,SEP1,SEP3andSEP4were detected both in the flower and fruit tissue andPIwas detected exclusively in flowers. KiwifruitFUL-likewas detected in leaf and flower tissues and was relatively highly expressed in the root.FULwas not detected in the root, but was detectable in vegetative shoot organs (stem and leaf) and was highly expressed in flower and particularly fruit. In general, the expression levels were relatively high compared with those of kiwifruitACTIN, with the exception ofFUL-likeandAG(Figure3).

Expression profiles ofActinidiaflowering genes in mature plant organs.实时rt - pcr分析Actinidiaflowering genes in the root, stem internode, leaf, flower and fruit of two kiwifruit cultivars,A. chinensis'Hort16A' (white rectangles) andA. deliciosa'Hayward' (black rectangles). The expression of each gene was normalized againstACTIN.Error bars represent SE for three replicate reactions.

Expression domains in normal and aberrant flowers

To further investigate the role of identified genes in specification of floral organ fate in kiwifruit, floral organs of normal and aberrantA. deliciosaflowers were analysed by RT-qPCR.A. deliciosapistillate (female) flowers consist of well separated whorls, with 5-6 ovate-oblong brown sepals, 5-6 convolute white petals (Figure4A), stamens that appear fully developed and a sub-globose, hairy ovary with numerous styles and ovules (Figure4B).The pedicel carries two small lateral bracts (Figure4A) that arise at very early stages of inflorescence development [61]。In some cases, lateral flowers can initiate and develop in the axils of these bracts. The staminate (male) flower is similar except for the stamens with longer filaments and larger anthers and underdeveloped ovary, which lacks styles and ovules (Figure4C, D).

Morphology ofActinidia deliciosaflowers.A-B.A. deliciosa'Hayward' pistillate (female) flower with sepals, petals, stamens and ovary with a fully developed stigma. Arrows indicate small lateral bracts. C-D.A. deliciosa'Chieftain' staminate (male) flower with sepals, petals, stamens and a rudimentary pistil. E-F.A. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' flower, severe phenotype, with spirally arranged large bracts in the base of the flower, multiple perianth whorls and a new flower with perianth only whorls in the centre. G-H.A. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' flower, moderate phenotype, with small bracts, sepals, multiple whorls of petals and underdeveloped reproductive structures. I. Sepaloid petal. J. Anther-like structure fused to the petal. K. An example of sampledA. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' floral organ tissues.

In aA. deliciosamutant 'Pukekohe dwarf', which bares staminate but sterile flowers, floral organs are characterized by a transition from bracts to outer and inner perianth and underdeveloped reproductive whorls. Most severely affected flowers have multiple, spirally arranged bract and perianth whorls (Figure4E), including intermediate floral organs (bract-like sepals, sepaloid petals). No reproductive organs are apparent and a new indeterminate flower is initiated instead (Figure4F).Moderately affected flowers consist of better separated whorls, including bracts, sepals, petals, underdeveloped stamens and filamentous pistils (Figure4G, H), as well as intermediate organs between each whorl, such as sepaloid outer petals (Figure4I) and anther structures fused to the upper part of inner petals (Figure4J).Because of the lack of sharp boundaries between 'Pukekohe dwarf' floral organs, the samples collected were bracts, sepals, sepaloid petals, petals, stamens with petaloid characteristics and the pistil-like structure (Figure4K).Leaf tissue was also included in the analysis.

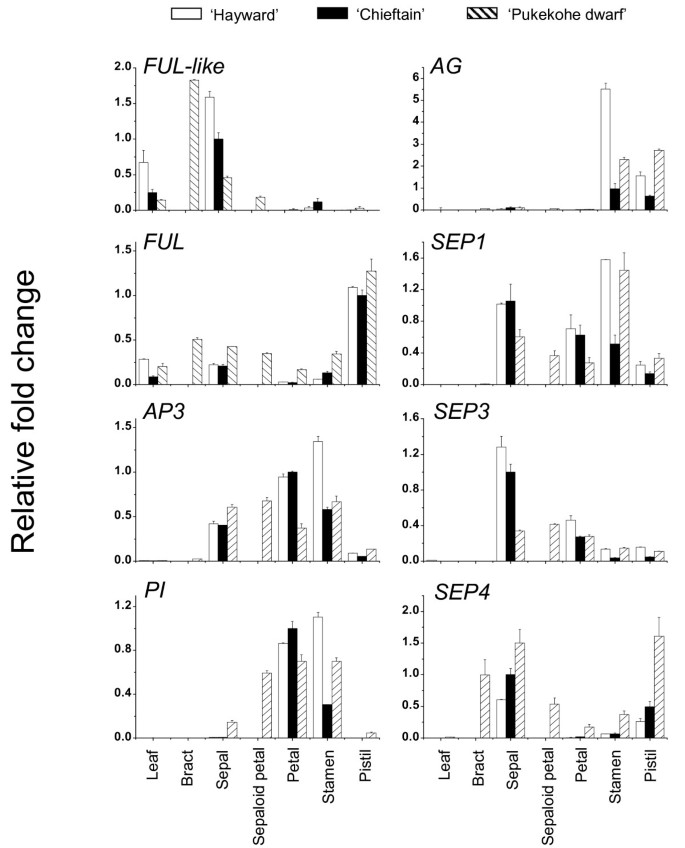

The expression patterns are presented in Figure5.In normal flowers,FUL-like表达to high level in sepals, and moderate level in the leaf tissue. Low levels of expression were detected in other flower organs.FULtranscript accumulated in all tissues, but the highest accumulation was detected in the pistil tissue.AP3-1was expressed in all floral organs, with higher accumulation detected in petal and stamen tissues, andPIwas exclusively expressed in petals and stamens.AGaccumulated in the reproductive flower organs, stamen and pistil.SEP1andSEP3were detected in all floral organs andSEP4accumulated in sepals and pistils, with low levels of transcript detected in stamens and almost no transcript detected in petals. No major differences were apparent between male and female flowers, with the exception of female stamen tissue that accumulated higher levels ofAP3-1,PI,AGandSEP1than those detected in male stamen tissues. Similar expression domains of kiwifruit flowering genes were detected inA. chinensisflowers (data not shown).

Expression profiles ofActinidiaflowering genes in normal and aberrant flowers.实时rt - pcr分析Actinidiaflowering genes in the leaf and floral organs ofA. deliciosa'Hayward' (female, normal), 'Chieftain' (male, normal) and 'Pukekohe dwarf' (aberrant) flowers. In addition to leaf, sepal, petal, stamen and pistil,A. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' analysis included bracts and sepaloid petals. White rectangles,A. deliciosa'Hayward'; black rectangles,A. deliciosa'Chieftain'; grey rectangles,A. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf'. The expression of each gene was normalized againstACTINand expressed as a ratio with 'Hayward' flower expression, which was set arbitrarily to 1. Error bars represent SE for three replicate reactions.

In aberrant 'Pukekohe dwarf' flowers, the accumulation of kiwifruit flowering transcripts was similar to that in normal flowers, with some exceptions.FUL-liketranscript was particularly abundant in bracts.FULalso accumulated in bracts to similar levels to those detected in leaves, sepals and stamens, but lower than pistil.PIexpression domain extended across all flower organs, while being restricted to petals and stamens in normal flowers.AGexpression was mainly confined to stamen and pistil tissue, with relative accumulation between that detected in male and female normal flowers.SEP1andSEP3accumulated from sepals to pistils but were absent from the leaf and bract tissue. On the other hand,SEP4accumulated in the bract tissue and was also abundant in aberrant flower pistils.

Expressions in kiwifruit emerging shoots

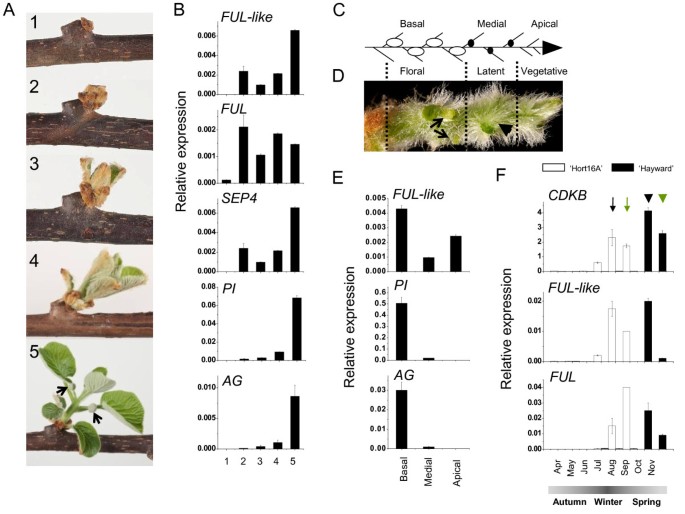

Expression of kiwifruit floral genes was further analysed in emerging shoots to address their role during budbreak and early stages of inflorescence and flower development. The timing and anatomical and morphological changes during shoot development are well described [4,8,61,62] and the collected samples (Figure6A) represented developmental stages as described using light and scanning electron microscopy by Polito and Grant [61]。KiwifruitFUL-like, FULandSEP4transcripts accumulated rapidly at the time of emergence of pubescent bud scales (Figure6B), a stage corresponding to early inflorescence development, when axillary meristem elongates and lateral bracts are initiated [61]。An increasing accumulation ofPIandAGwere detected from the bud scale emergence and leaf emergence stage, respectively (Figure6B), during rapid sequential floral organ development [61]。The accumulation ofPIandAGwas confined to the basal part of the emerging shoot where floral differentiation takes place, and was not detected in the vegetative shoot tip (Figure6C-E).The timing ofFUL-likeandFULaccumulation in the field-grown plants corresponded with initial stages of bud outgrowth inA. chinensisandA. deliciosa(Figure6F) and was similar to the accumulation pattern of a cell cycle geneCDKB1, used as a marker of cell divisions [63]。

Expression profiles ofActinidiaflowering genes in kiwifruit emerging shoots.A. Stages of budbreak and early shoot development inA. chinensisas described previously [61]。1、休眠芽;2,出现青春期的花蕾cales; 3, emergence of leaves; 4, unfolding of leaves and internode elongation; 5, clearly visible flower buds (arrows). Emergence of pubescent bud scales coincides with inflorescence development, when elongation of axillary meristem which gives rise to the terminal flower and initiation of bracts were detected. Leaf emergence coincides with completed sepal initiation and emergence of petal primordia. Unfolding of leaves coincides with carpel initiation [61]。B. Relative expression of kiwifruit flowering genes during shoot bud dormancy and early shoot development inA. chinensis.C. Schematic diagram representing the kiwifruit shoot and buds. D. Floral buds (arrows) become visible in the basal part of the stage 4 emerging shoot upon removal of leaves, but are absent from the medial part of the shoot (arrowhead). E. Relative expression of kiwifruit flowering genes in basal, medial and apical fragments of the stage 4 emerging shoot. F. Relative expression in shoot primordia during the season. Black arrow and arrowhead indicate visible emergence of pubescent bud scales inA. chinensis'Hort16A' andA. deliciosa'Hayward', respectively. Green arrow and arrowhead indicate leaf emergence inA. chinensis'Hort16A' and A. deliciosa 'Hayward', respectively.

Discussion

Kiwifruit flowering genes specify floral meristem and floral organ fates

A kiwifruit flower belongs to the regular eudicot flower type in which the floral organ identity is determined by expression and interaction of floral organ identity genes. Thus, a candidate gene approach was chosen for molecular analysis of kiwifruit flowering. Putative orthologs of genes controlling flower development were isolated and characterized from the EST collection comprising transcripts from a variety of tissues of severalActinidiaspecies, including flower, developing buds and fruit [12]。The EST collection is biased towards fruit transcripts and many of the ESTs for floral organ identity were identified in fruit libraries: kiwifruitFUL,AP3,AG,SEP1,SEP3andSEP4were all represented with at least one sequence in a library derived from fruit transcripts (Table1).All these genes have been confirmed as expressed in the fruit, in addition to the flower.FUL-likewas identified from the leaf library and the presence of only one sequence correlated with its low expression levels as compared toACTIN.Phylogenetic analysis and phenotypes obtained upon ectopic expression inArabidopsissuggested evolutionary and functional conservation of kiwifruit flowering genes.

These data taken together with expression patterns in normal and aberrant kiwifruit flowers confirmed that the identified B-, C- and E-class genes have a role in specification of kiwifruit floral organs. The floral promotion obtained upon overexpression inArabidopsis, elevated expression in 'Pukekohe dwarf' bracts and accumulation at the earliest stages of bud development strongly suggested a role for kiwifruitFUL-like,FULandSEP4in floral meristem specification. The mechanism of kiwifruit FUL-like and FUL action is unknown, but might be related to promotion or maintenance of cellular expansion and differentiation, as reported for FUL inArabidopsis[64]。Expression in vegetative tissues would support the role forFUL-likeandFULgenes in general cellular function. While kiwifruitSEP4might perform a similar general function, it marks the inflorescence, flower and fruit development, based on the transcript absence from vegetative tissues. The increasing accumulation during shoot emergence and expression confined to reproductive organs suggestedPIandAGas markers of flower differentiation.

Is there an AP1-like gene in kiwifruit?

It is unclear if anAP1orthologous gene exists in the kiwifruit genome. None of the candidate genes mined from the EST database or described previously [5] contained the carboxyl-terminal CFAT/A farnesylation motif characteristic of euAP1 proteins [65]。It is therefore possible that an unidentified kiwifruit euAP1 protein is required for sepal and petal identity. On the other hand, the role of euAP1genes in specification of sepal and petal identity in plants other thanArabidopsisis unclear and the concept of the A function in flower organ identity may not be universal [52,53]。In general, the role of A function genes in organ identity might simply be the result of their meristem identity function and the mutant floral organ phenotypes could be explained by incomplete transition to a floral meristem [54]。In addition, the numerous duplication events that gave rise to the angiospermAP1/FUL-like gene family [44,66–68] make it difficult to identify the true orthologs across plant taxa.FULgenes also perform the floral meristem identity function [36,69–71] and possibly the A function [72–74], and the AP1 conserved motif and protein modification may not be necessary [75]。A possibility exists that kiwifruitFUL-likemay have a role in sepal specification, based on its expression pattern in flowers. However, expression ofFUL-likefailed to rescue theap1-1organ identity phenotype (data not shown) and a yeast-two-hybrid assay failed to identify an interaction between FUL-like and any of the kiwifruit SEP proteins, that would have been predicted from the quartet model [28,32]。结合营养ki的表达式wifruit organs, these data suggest against the A function of kiwifruitFUL-like.

A. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' mutant - a tool to study kiwifruit flower development

Functional characterization of a gene typically includes analysis of phenotypes resulting from a mutation or ectopic expression of the gene. In kiwifruit, artificially generated mutations are difficult to generate and screen and genetic transformation is a difficult and lengthy process. However, natural genetic variants exist with altered floral development and morphology that can be utilized as a genetic tool to identify and characterize genes involved in flowering.A. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' flower is characterized by numerous bracts preceding sepals. Given the position on the pedicel, spiral phyllotaxis and morphology significantly different from that of both leaves and sepals, bracts can be seen as modified leaves produced during the early stages of the floral transition, that arise as a result of increasing activity of floral-promoting genes. Thus, the significant up-regulation of kiwifruitFUL-like,FULandSEP4in bracts further suggests their role in establishment of floral fate, consistent with floral promotion seen upon expression of these genes inArabidopsis.The other unusual feature of 'Pukekohe dwarf' flowers is the presence of multiple perianth whorls with gradual transition between floral organs and the presence of intermediate organs with combined sepal and petal or petal and anther identity. Accordingly, kiwifruitPIexpression domain in 'Pukekohe dwarf' is extended and resembles the 'fading border' model of floral gene expression [57]。

The molecular mechanisms involved in the generation of the mutation and the target genes affected in 'Pukekohe dwarf' are unknown. 'Pukekohe dwarf' is impaired in the specification of stamen/anther and pistil/carpel identity, but not in development of perianth organs, resembling the loss-of-function mutation in class C geneAG[13,22]。However, no major differences were detected in the expression pattern or sequence of kiwifruitAGbetween normal and aberrant flowers (Additional file2), suggesting that a different mechanism might underlie the 'Pukekohe dwarf' phenotype. Given that the mutation likely occurs in one copy of the target gene, it is highly probable that the phenotype is the result of a gain-of-function rather than loss-of-function mutation.

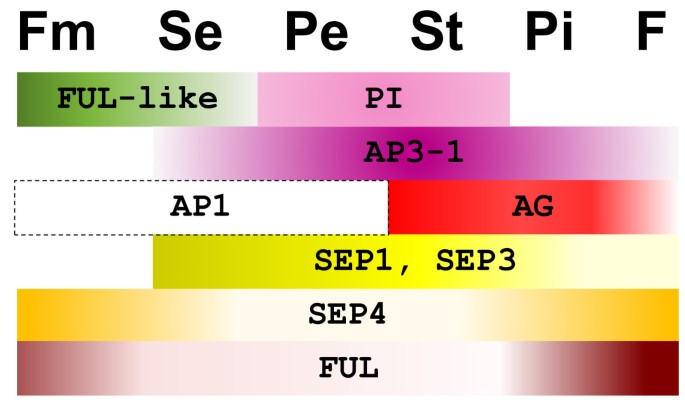

A model for kiwifruit floral organ identity

Based on the relative accumulation of kiwifruit MADS-box gene transcripts in the wild-type male and female flowers and 'Pukekohe dwarf' mutant flowers, a model of kiwifruit floral organ specification was proposed (Figure7).锋利的基因表达边界结合gradients of gene expression within the expression domains are responsible for the (A)BCE-like floral organ identity in the wild type, regular, four-whorled kiwifruit flower. The A function may require a yet unidentified AP1-like protein, or is derived from floral meristem specifying factors, e.g. FUL-like, FUL and SEP4 proteins; their accumulation is sufficient to promote bracts as intermediates between leaves and sepals, but additional SEP proteins (SEP1 or SEP3) are required for true sepal-identity. Extended PI expression in the mutant is the likely reason for extended petaloid features and multiple petal whorls.

Conclusions

Over the past decades, kiwifruit has developed into an important horticultural crop, firstly in New Zealand and subsequently in other countries. Current research on kiwifruit is mainly focused around consumer-driven traits such as fruit flavour and fragrance, appearance, healthful components and convenience, but the knowledge of the genetic regulation of flowering is very scarce. This report provides a description of flower development in kiwifruit at the molecular level. It has identified genes that will be utilized as genetic markers for inflorescence and flower development and candidates that are expected to have an impact on kiwifruit growth, phase change and time of flowering.

Methods

Plant materials

The majority of the plant material used in this study was collected from two female cultivars that are grown commercially in New Zealand: 'Hort16A' (A. chinensisPlanch.) and'Hayward' (A. deliciosa(A. Chev.) C.F. Liang et A.R. Ferguson). For expression studies in mature flowers, in addition to femaleA. deliciosa'Hayward' normal flowers, maleA. deliciosa'Chieftain' normal flowers andA. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' aberrant flowers were used. All kiwifruit plants were grown in the orchard under natural climatic conditions. The vines were trained on a T-bar training system and underwent pruning according to standard orchard management practice. All studies were carried out on tissue collected from at least six individual plants, with the exception of 'Pukekohe dwarf', where only one plant was available.

Root, stem, leaf, flower, and fruit tissue collection was carried out onA. chinensis'Hort16A' andA. deliciosa'Hayward' vines growing at the Plant & Food Research orchard near Kerikeri, New Zealand, during the spring and summer season of 2005-06. Mature flower organ tissues were collected fromA. deliciosa'Hayward', 'Chieftain' and 'Pukekohe dwarf' growing in the research orchard near Te Puke, New Zealand, during the season of 2006-2007.

For expression analysis during early shoot development, kiwifruit vines (canes) were collected fromA. chinensis'Hort16A' grown in the research orchard near Te Puke, New Zealand in autumn 2010. The canes were stored at 4°C for three weeks. Excised canes are frequently used in budbreak and flowering studies and cold storage is a standard practice that maintains buds at dormant state [76]。Bud development was initiated upon immersion of lower side of the cane in water and maintenance in 24°C and natural light. Whole dormant buds and emerging shoots were collected. For analysis in the fragments of the emerging shoot, unfolding leaves were removed prior to collection of the basal (flower-bearing), medial and apical fragments.

For seasonal expression analysis, samples were collected from autumn to late spring at monthly intervals from A.chinensis'Hort16A' andA. deliciosa“海沃德”葡萄树生长在研究果园near Te Puke, New Zealand, during the season of 2006-2007. Shoot primordia were dissected from axillary buds from the second, third and fourth node distal to the most distal fruit and represented the same developmental unit, starting as latent buds established during the first season that were dormant over the winter months and resumed development and outgrowth in the spring. The last two samples collected corresponded to emergence of pubescent bud scales and leaf emergence, respectively.

Arabidopsis thaliana'Columbia' (Col-0) ecotype plants were grown in the greenhouse under a long day (21°C, 14/10 h light/dark) or short day regime (21°C, 8/16 h light/dark).

Phylogeny

TheActinidiaEST database [12] was interrogated using BLAST analysis [77]。Kiwifruit EST sequences were uploaded to Vector NTI version 9.0.0http://www.invitrogen.com.Sequence alignment was performed using Vector NTI Clustal W (opening 15, extension penalty 0.3). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using MEGA version 3.1 [78] using a minimum evolution phylogeny test and 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Gene isolation and vector construction

Clones containing full-length cDNA ofFUL-like,FUL,AP3,PI,SEP3andSEP4were obtained from the Plant & Food ResearchActinidiaEST library [12]。cDNA ofFUL-like,FULandSEP3were cloned asSpeI-XhoI fragments into the corresponding sites of pSAK778 binary vector [79]。cDNA ofSEP4was cloned as anAsp718-Xba我的片段the corresponding sites of pART277 binary vector, produced by cloning the pART7NotI CaMV35S-mcs-ocs3'cassette into theNotI site of pART27 [80]。cDNAs ofAP3andPI, flanked by the attB1 and attB2 sequences in pCMV-SPORT6 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies Corp.), were transferred to the Gateway-adapted pHEX2 destination binary vector [81], via the pDONR221 intermediate vector, using Gateway recombination cloning, with all reactions performed as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Full-length cDNA copy ofAGwas isolated fromA. chinensisflower cDNA using PCR amplification (primer sequences listed in Additional file3), cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) for sequencing purposes and further cloned asSpeI-Xba我的片段corresponding sites of pSAK778 binary vector [79]。Construction of these plant transformation vectors placed each full-length cDNA between the CaMV 35S promoter and ocs 3' transcriptional terminator. The resulting plasmids were transformed intoAgrobacterium tumefaciensstrain GV3101 by the electroporation method.

Arabidopsistransformation

Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated plant transformation was performed by the floral dipping method [82]。Seeds of transgenic plants were selected on 1/2 MS medium supplemented with kanamycin and placed in a growth room under appropriate day-length conditions.

RNA extraction and expression studies

Total RNA was isolated from kiwifruit tissue as described by Gasic et al [83]。The concentration of RNA was determined using the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using RNA treated with DNase I (Invitrogen), an oligo(dT) primer and the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantifications using real-time PCR were performed with the FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I reaction mix (Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany) using the Lightcycler 1.5 instrument and the LightCycler Software version 4 (Roche Diagnostics). Primers were designed to produce amplification products within the range of 160-260 nucleotides. Primer sequences are listed in Additional file3.The specificity of primer pairs was confirmed by melting curve analysis of PCR products and agarose gel electrophoresis followed by sequencing. Reactions were performed in triplicates and a negative water control was included in each run. Products were quantified against the standard curve using dilutions of a sample with the highest expression and the expression was normalized to kiwifruitACTIN(GenBank accession number FG403300). Error bars shown in the qPCR data represent the standard error (SE) of three replicate PCR reactions.

Yeast-two-hybrid assays

Full-length open reading frames ofActinidiaMADS-box genes were amplified using a two-step adapter PCR strategy which incorporated the complete attB sequence (Additional file3).The PCR fragment was recombined in the Gateway™ pDONR221 vector, resulting in an entry clone. All entry clones were verified using sequence analysis before cloning in the yeast two-hybrid GAL4 binding domain vector pDEST32 (bait) and GAL4 activating domain vector pDEST22 (prey). Bait vectors were transformed into yeast strain PJ69-4α (MATα;[84]) and prey vectors into strain PJ69-4a (MATa;[84]) and selected on SC plates lacking Leu and Trp, respectively. The baits and preys were systematically mated by spotting 5 μL droplets on top of each other on SC complete plates. After overnight incubation at 30°C, the yeast was transferred to SC plates lacking Leu and Trp to select for diploid yeast containing both plasmids, and incubated at 30°C for 2 days. This transfer was performed once more, after which the yeast was transferred to separate selection plates containing SC medium lacking Trp, Leu and His and supplemented with 0, 1, 3 or 5 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole. Plates were incubated for four days at 20°C and scored for growth. The screening was performed in duplicate.

References

- 1.

Huang HW, Ferguson AR: Genetic resources of kiwifruit: domestication and breeding. Horticultural Reviews. 2007, 33: 1-121.

- 2.

Ferguson AR: The genusActinidia.Kiwifruit: science and management. Edited by: Warrington IJW, GC. 1990, Auckland: Ray Richards Publisher and New Zealand Society for Horticultural Science, 15-35.

- 3.

Snowball AM: Seasonal cycle of shoot development in selectedActinidiaspecies. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science. 1997, 25: 221-231.

- 4.

Walton EF, Fowke PJ, Weis K, McLeay PL: Shoot axillary bud morphogenesis in kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa).Annals of Botany. 1997, 80: 13-21.

- 5.

Walton EF, Podivinsky E, Wu RM: Bimodal patterns of floral gene expression over the two seasons that kiwifruit flowers develop. Physiol Plant. 2001, 111 (3): 396-404.

- 6.

Foster TM, Seleznyova AN, Barnett AM: Independent control of organogenesis and shoot tip abortion are key factors to developmental plasticity in kiwifruit (Actinidia).Ann Bot. 2007, 100 (3): 471-481.

- 7.

Watson M, Gould KS: Development of flat and fan-shaped fruit inActinidia chinensisvar. chinensis andActinidia deliciosa.Ann Bot. 1994, 74 (1): 59-68.

- 8.

Brundell DJ: Flower development of the Chinese gooseberry (Actinidia chinensisPlanch.). I. Development of the flower shoot. New Zealand Journal of Botany. 1975, 13: 473-483.

- 9.

曼森PJ Snelgar WP:确定时间啊f flower evocation in kiwifruit vines. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science. 1992, 20: 439-447.

- 10.

Fabbri A, Lisetti M, Benelli C: Studies on flower induction in kiwifruit. Acta Horticulturae. 1992, 297: 217-222.

- 11.

Snowball AM: The timing of flower evocation in kiwifruit. Journal of Horticultural Science. 1996, 66: 261-273.

- 12.

Crowhurst RN, Gleave AP, MacRae EA, Ampomah-Dwamena C, Atkinson RG, Beuning LL, Bulley SM, Chagne D, Marsh KB, Matich AJ, Montefiori M, Newcomb RD, Schaffer RJ, Usadel B, Allan AC, Boldingh HL, Bowen JH, Davy MW, Eckloff R, Ferguson AR, Fraser LG, Gera E, Hellens RP, Janssen BJ, Klages K, Lo KR, MacDiarmid RM, McNeilage MA, Rassam M, et al: Analysis of expressed sequence tags fromActinidia: applications of a cross species EST database for gene discovery in the areas of flavor, health, color and ripening. BMC Genomics. 2008, 9 (1): 351-

- 13.

Coen ES, Meyerowitz EM: The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature. 1991, 353 (6339): 31-37.

- 14.

Weigel D, Meyerowitz EM: The ABCs of floral homeotic genes. Cell. 1994, 78 (2): 203-209.

- 15.

Mandel MA, Gustafson-Brown C, Savidge B, Yanofsky MF: Molecular characterization of theArabidopsisfloral homeotic geneAPETALA1.Nature. 1992, 360 (6401): 273-277.

- 16.

Bowman JL, Alvarez J, Weigel D, Meyerowitz EM, Smyth DR: Control of flower development inArabidopsis thalianabyAPETALA1and interacting genes. Development. 1993, 119 (3): 721-743.

- 17.

Sommer H, Beltran JP, Huijser P, Pape H, Lonnig WE, Saedler H, Schwarz-Sommer Z:Deficiens, a homeotic gene involved in the control of flower morphogenesis inAntirrhinum majus: the protein shows homology to transcription factors. Embo J. 1990, 9 (3): 605-613.

- 18.

Jack T, Brockman LL, Meyerowitz EM: The homeotic geneAPETALA3ofArabidopsis thalianaencodes a MADS box and is expressed in petals and stamens. Cell. 1992, 68 (4): 683-697.

- 19.

Schwarz-Sommer Z, Hue I, Huijser P, Flor PJ, Hansen R, Tetens F, Lonnig WE, Saedler H, Sommer H: Characterization of theAntirrhinumfloral homeotic MADS-box genedeficiens: evidence for DNA binding and autoregulation of its persistent expression throughout flower development. Embo J. 1992, 11 (1): 251-263.

- 20.

Trobner W, Ramirez L, Motte P, Hue I, Huijser P, Lonnig WE, Saedler H, Sommer H, Schwarz-Sommer Z:GLOBOSA: a homeotic gene which interacts withDEFICIENSin the control ofAntirrhinumfloral organogenesis. Embo J. 1992, 11 (13): 4693-4704.

- 21.

Goto K, Meyerowitz EM: Function and regulation of theArabidopsisfloral homeotic genePISTILLATA.Genes Dev. 1994, 8 (13): 1548-1560.

- 22.

Yanofsky MF, Ma H, Bowman JL, Drews GN, Feldmann KA, Meyerowitz EM: The protein encoded by theArabidopsishomeotic geneagamous像转录因子。大自然。1990年,346年(6279): 35-39.

- 23.

Bradley D, Carpenter R, Sommer H, Hartley N, Coen E: Complementary floral homeotic phenotypes result from opposite orientations of a transposon at theplenalocus ofAntirrhinum.Cell. 1993, 72 (1): 85-95.

- 24.

Irish VF, Sussex IM: Function of theapetala-1gene duringArabidopsisfloral development. Plant Cell. 1990, 2 (8): 741-753.

- 25.

Jofuku KD, den Boer BG, Van Montagu M, Okamuro JK: Control ofArabidopsisflower and seed development by the homeotic geneAPETALA2.Plant Cell. 1994, 6 (9): 1211-1225.

- 26.

Bowman JL, Drews GN, Meyerowitz EM: Expression of theArabidopsisfloral homeotic geneAGAMOUSis restricted to specific cell types late in flower development. Plant Cell. 1991, 3 (8): 749-758.

- 27.

Kunst L, Klenz JE, Martinez-Zapater J, Haughn GW: AP2 Gene Determines the Identity of Perianth Organs in Flowers ofArabidopsis thaliana.Plant Cell. 1989, 1 (12): 1195-1208.

- 28.

Melzer R, Theissen G: Reconstitution of 'floral quartets' in vitro involving class B and class E floral homeotic proteins. Nucleic acids research. 2009, 37 (8): 2723-2736.

- 29.

Pelaz S, Ditta GS, Baumann E, Wisman E, Yanofsky MF: B and C floral organ identity functions requireSEPALLATAMADS-box genes. Nature. 2000, 405 (6783): 200-203.

- 30.

Pelaz S, Gustafson-Brown C, Kohalmi SE, Crosby WL, Yanofsky MF:APETALA1andSEPALLATA3interact to promote flower development. Plant J. 2001, 26 (4): 385-394.

- 31.

Theissen G, Saedler H: Plant biology. Floral quartets. Nature. 2001, 409 (6819): 469-471.

- 32.

Pinyopich A, Ditta GS, Savidge B, Liljegren SJ, Baumann E, Wisman E, Yanofsky MF: Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature. 2003, 424 (6944): 85-88.

- 33.

Ditta G, Pinyopich A, Robles P, Pelaz S, Yanofsky MF: TheSEP4gene ofArabidopsis thalianafunctions in floral organ and meristem identity. Curr Biol. 2004, 14 (21): 1935-1940.

- 34.

Honma T, Goto K: Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature. 2001, 409 (6819): 525-529.

- 35.

Mandel MA, Yanofsky MF: A gene triggering flower formation inArabidopsis.Nature. 1995, 377 (6549): 522-524.

- 36.

Ferrandiz C, Gu Q, Martienssen R, Yanofsky MF: Redundant regulation of meristem identity and plant architecture byFRUITFULL,APETALA1andCAULIFLOWER.Development. 2000, 127 (4): 725-734.

- 37.

Jofuku KD, Omidyar PK, Gee Z, Okamuro JK: Control of seed mass and seed yield by the floral homeotic geneAPETALA2.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102 (8): 3117-3122.

- 38.

Wurschum T, Gross-Hardt R, Laux T:APETALA2regulates the stem cell niche in theArabidopsisshoot meristem. Plant Cell. 2006, 18 (2): 295-307.

- 39.

Ma H, dePamphilis C: The ABCs of floral evolution. Cell. 2000, 101 (1): 5-8.

- 40.

Kaufmann K, Melzer R, Theißen G: MIKC-type MADS-domain proteins: structural modularity, protein interactions and network evolution in land plants. Gene. 2005, 347 (2): 183-198.

- 41.

Vandenbussche M, Zethof J,苏E, ko R, Tornielli GB, Pezzotti M, Ferrario S, Angenent GC, Gerats T: Toward the analysis of the petunia MADS box gene family by reverse and forward transposon insertion mutagenesis approaches: B, C, and D floral organ identity functions requireSEPALLATA-Like MADS box genes in petunia. Plant Cell. 2003, 15 (11): 2680-2693.

- 42.

Hileman LC, Sundstrom JF, Litt A, Chen M, Shumba T, Irish VF: Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the MADS-box gene family in tomato. Mol Biol Evol. 2006, 23 (11): 2245-2258.

- 43.

Theissen G, Kim JT, Saedler H: Classification and phylogeny of the MADS-box multigene family suggest defined roles of MADS-box gene subfamilies in the morphological evolution of eukaryotes. J Mol Evol. 1996, 43 (5): 484-516.

- 44.

Becker A, Theissen G: The major clades of MADS-box genes and their role in the development and evolution of flowering plants. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 29 (3): 464-489.

- 45.

Parenicova L, de Folter S, Kieffer M, Horner DS, Favalli C, Busscher J, Cook HE, Ingram RM, Kater MM, Davies B, Angenent GC, Colombo L: Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: new openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell. 2003, 15 (7): 1538-1551.

- 46.

Nam J, dePamphilis CW, Ma H, Nei M: Antiquity and evolution of the MADS-box gene family controlling flower development in plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2003, 20 (9): 1435-1447.

- 47.

Hecht V, Foucher F, Ferrandiz C, Macknight R, Navarro C, Morin J, Vardy ME, Ellis N, Beltran JP, Rameau C, Weller JL: Conservation ofArabidopsisFlowering Genes in Model Legumes. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137 (4): 1420-1434.

- 48.

Kater MM, Dreni L, Colombo L: Functional conservation of MADS-box factors controlling floral organ identity in rice andArabidopsis.Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006, 57 (13): 3433-3444.

- 49.

Leseberg CH, Li AL, Kang H, Duvall M, Mao L: Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family inPopulus trichocarpa.Gene. 2006, 378: 84-94.

- 50.

Diaz-Riquelme J, Lijavetzky D, Martinez-Zapater JM, Carmona MJ: Genome-Wide Analysis of MIKCC-Type MADS Box Genes in Grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149 (1): 354-369.

- 51.

Ng M, Yanofsky MF: Function and evolution of the plant MADS-box gene family. Nat Rev Genet. 2001, 2 (3): 186-195.

- 52.

Schwarz-Sommer Z, Huijser P, Nacken W, Saedler H, Sommer H: Genetic Control of Flower Development by Homeotic Genes inAntirrhinum majus.Science. 1990, 250 (4983): 931-936.

- 53.

Huijser P, Klein J, Lonnig WE, Meijer H, Saedler H, Sommer H: Bracteomania, an inflorescence anomaly, is caused by the loss of function of the MADS-box gene squamosa inAntirrhinum majus.Embo J. 1992, 11 (4): 1239-1249.

- 54.

Litt A: An Evaluation of A-Function: Evidence from theAPETALA1andAPETALA2Gene Lineages. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2007, 168 (1): 73-91.

- 55.

Bowman J: Evolutionary conservation of angiosperm flower development at the molecular and genetic levels. Journal of Biosciences. 1997, 22 (4): 515-527.

- 56.

Kramer EM, Di Stilio VS, Schluter PM: Complex Patterns of Gene Duplication in theAPETALA3andPISTILLATA血统的毛茛科doi: 10.1086/344694。International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2003, 164 (1): 1-11.

- 57.

Buzgo M, Soltis PS, Soltis DE: Floral Developmental Morphology ofAmborella trichopoda(Amborellaceae) doi:10.1086/424024. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2004, 165 (6): 925-947.

- 58.

Litt A, Kramer EM: The ABC model and the diversification of floral organ identity. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2010, 21 (1): 129-137.

- 59.

Kramer EM, Jaramillo MA, Di Stilio VS: Patterns of gene duplication and functional evolution during the diversification of theAGAMOUSsubfamily of MADS box genes in angiosperms. Genetics. 2004, 166 (2): 1011-1023.

- 60.

Mizukami Y, Ma H: Ectopic expression of the floral homeotic geneAGAMOUSin transgenicArabidopsisplants alters floral organ identity. Cell. 1992, 71 (1): 119-131.

- 61.

Polito VS, Grant JA: Initiation and development of pistillate flowers inActinidia chinensis.Scientia Horticulturae. 1984, 22 (4): 365-371.

- 62.

Brundell DJ: Flower development of the Chinese goosberry (Actinidia chinensisPlanch.). II Development of the flowering bud. New Zealand Journal of Botany. 1975, 13: 485-496.

- 63.

Walton EF, Wu RM, Richardson AC, Davy M, Hellens RP, Thodey K, Janssen BJ, Gleave AP, Rae GM, Wood M, Schaffer RJ: A rapid transcriptional activation is induced by the dormancy-breaking chemical hydrogen cyanamide in kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) buds. J Exp Bot. 2009, 60 (13): 3835-3848.

- 64.

Gu Q, Ferrandiz C, Yanofsky M, Martienssen R: TheFRUITFULLMADS-box gene mediates cell differentiation duringArabidopsisfruit development. Development. 1998, 125 (8): 1509-1517.

- 65.

Yalovsky S, Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Bracha K, Toledo-Ortiz G, Gruissem W: Prenylation of the floral transcription factor APETALA1 modulates its function. Plant Cell. 2000, 12 (8): 1257-1266.

- 66.

Litt A, Irish VF: Duplication and diversification in theAPETALA1/FRUITFULLfloral homeotic gene lineage: implications for the evolution of floral development. Genetics. 2003, 165 (2): 821-833.

- 67.

Preston JC, Kellogg EA: Reconstructing the evolutionary history of paralogousAPETALA1/FRUITFULL-like genes in grasses (Poaceae). Genetics. 2006, 174 (1): 421-437.

- 68.

Purugganan MD, Rounsley SD, Schmidt RJ, Yanofsky MF: Molecular evolution of flower development: diversification of the plant MADS-box regulatory gene family. Genetics. 1995, 140 (1): 345-356.

- 69.

Preston JC, Kellogg EA: Conservation and divergence ofAPETALA1/FRUITFULL-like gene function in grasses: evidence from gene expression analyses. Plant J. 2007, 52 (1): 69-81.

- 70.

Danyluk J, Kane NA, Breton G, Limin AE, Fowler DB, Sarhan F: TaVRT-1, a putative transcription factor associated with vegetative to reproductive transition in cereals. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132 (4): 1849-1860.

- 71.

Muller BM, Saedler H, Zachgo S: The MADS-box geneDEFH28fromAntirrhinumis involved in the regulation of floral meristem identity and fruit development. Plant J. 2001, 28 (2): 169-179.

- 72.

Gocal GF, King RW, Blundell CA, Schwartz OM, Andersen CH, Weigel D: Evolution of floral meristem identity genes. Analysis ofLolium temulentumgenes related toAPETALA1andLEAFYofArabidopsis.Plant Physiol. 2001, 125 (4): 1788-1801.

- 73.

Prasad K, Parameswaran S, Vijayraghavan U:OsMADS1, a rice MADS-box factor, controls differentiation of specific cell types in the lemma and palea and is an early-acting regulator of inner floral organs. Plant J. 2005, 43 (6): 915-928.

- 74.

Prasad K, Sriram P, Kumar CS, Kushalappa K, Vijayraghavan U: Ectopic expression of riceOsMADS1揭示了一个角色在指定引理和内稃,grass floral organs analogous to sepals. Dev Genes Evol. 2001, 211 (6): 281-290.

- 75.

Berbel A, Navarro C, Ferrandiz C, Canas LA, Madueno F, Beltran JP: Analysis ofPEAM4, the peaAP1functional homologue, supports a model forAP1-like genes controlling both floral meristem and floral organ identity in different plant species. Plant J. 2001, 25 (4): 441-451.

- 76.

Snowball AM: Excised canes are a suitable test system for the study of budbreak and flowering of kiwifruit canes. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science. 1997, 25: 141-148.

- 77.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215 (3): 403-410.

- 78.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M: MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004, 5 (2): 150-163.

- 79.

Drummond RS, Martinez-Sanchez NM, Janssen BJ, Templeton KR, Simons JL, Quinn BD, Karunairetnam S, Snowden KC:Petunia hybrida CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE7is involved in the production of negative and positive branching signals in petunia. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151 (4): 1867-1877.

- 80.

Gleave AP: A versatile binary vector system with a T-DNA organisational structure conducive to efficient integration of cloned DNA into the plant genome. Plant Mol Biol. 1992, 20 (6): 1203-1207.

- 81.

Hellens R, Allan A, Friel E, Bolitho K, Grafton K, Templeton M, Karunairetnam S, Gleave A, Laing W: Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods. 2005, 1 (1): 13-

- 82.

Clough SJ, Bent AF: Floral dip: a simplified method forAgrobacterium-mediated transformation ofArabidopsis thaliana.Plant J. 1998, 16 (6): 735-743.

- 83.

Gasic K, Hernandez A, Korban SS: RNA Extraction From Different Apple Tissues Rich in Polyphenols and Polysaccharides for cDNA Library Construction. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2004, 22: 437a-437g.

- 84.

James P, Halladay J, Craig EA: Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996, 144 (4): 1425-1436.

- 85.

Kramer EM, Dorit RL, Irish VF: Molecular evolution of genes controlling petal and stamen development: duplication and divergence within theAPETALA3andPISTILLATAMADS-box gene lineages. Genetics. 1998, 149 (2): 765-783.

- 86.

Ampomah-Dwamena C, Morris BA, Sutherland P, Veit B, Yao J-L: Down-regulation ofTM29, a tomatoSEPALLATAhomolog, causes parthenocarpic fruit development and floral reversion 10.1104/pp.005223. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130 (2): 605-617.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mark McNeilage for help with theA. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' mutant, Lekha Sreekantan for involvement in early stages of the project, Andrew Gleave, Sakuntala Karunairetnam and Bhawana Nain for cloning and sequencing support, Tim Holmes for photography, and Anne Gunson for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was funded by the New Zealand Foundation for Research, Science and Technology grant C10X0816 MeriNET.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

EV-G conceived the project, acquired the funding, designed the experiments, conducted analyses and prepared the manuscript. SMM participated inArabidopsistransformation and RNA extraction and expression studies. CV carried out the yeast-two-hybrid assays and contributed to the manuscript. RW participated in RNA extraction and expression studies. RHL and Y-YW participated in gene isolation and vector construction. RPH participated in the sequence alignment and has given final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12870_2011_857_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: Intron characteristic ofAGC lineage, An intron located in the last codon of predictedActinidia AGgene was amplified fromA. deliciosa'Hayward' andA. chinensis"Hort16A'. The presence of this intron is characteristic for the C but not the D lineage of the angiosperm AG subfamily. Three types of intron sequences were obtained from a hexaploid 'Hayward' (one 95 bp and two 188 bp in length) and one type was amplified from a diploid 'Hort16A' (193 bp). (PDF 46 KB)

Nucleotide sequence alignment of

Additional file 2:Actinidia AGcDNA.cDNA was amplified fromA. chinensis'Hort16A',A. deliciosa'Hayward' andA. deliciosa'Pukekohe dwarf' flower cDNA. TheA. arguta AGsequence was obtained from theActinidiaEST database. (PDF 34 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Varkonyi-Gasic, E., Moss, S.M., Voogd, C.et al.Identification and characterization of flowering genes in kiwifruit: sequence conservation and role in kiwifruit flower development.BMC Plant Biol11,72 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-72

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Keywords

- Floral Organ

- Floral Meristem

- Floral Transition

- Floral Organ Identity

- Floral Meristem Identity