- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

A novel RNA binding protein affectsrbcL gene expression and is specific to bundle sheath chloroplasts in C4plants

BMC Plant Biology体积13, Article number:138(2013)

Abstract

Background

Plants that utilize the highly efficient C4pathway of photosynthesis typically possess kranz-type leaf anatomy that consists of two morphologically and functionally distinct photosynthetic cell types, the bundle sheath (BS) and mesophyll (M) cells. These two cell types differentially express many genes that are required for C4capability and function. In mature C4leaves, the plastidicrbcL gene, encoding the large subunit of the primary CO2fixation enzyme Rubisco, is expressed specifically within BS cells. Numerous studies have demonstrated that BS-specificrbcL gene expression is regulated predominantly at post-transcriptional levels, through the control of translation and mRNA stability. The identification of regulatory factors associated with C4patterns ofrbcL gene expression has been an elusive goal for many years.

Results

RLSB, encoded by the nuclearRLSBgene, is an S1-domain RNA binding protein purified from C4chloroplasts based on its specific binding to plastid-encodedrbcL mRNAin vitro.Co-localized with LSU to chloroplasts, RLSB is highly conserved across many plant species. Most significantly, RLSB localizes specifically to leaf bundle sheath (BS) cells in C4plants. Comparative analysis using maize (C4) andArabidopsis(C3) reveals its tight association withrbcL gene expression in both plants. ReducedRLSBexpression (through insertion mutation or RNA silencing, respectively) led to reductions inrbcL mRNA accumulation and LSU production. Additional developmental effects, such as virescent/yellow leaves, were likely associated with decreased photosynthetic function and disruption of associated signaling networks.

Conclusions

Reductions inRLSBexpression, due to insertion mutation or gene silencing, are strictly correlated with reductions inrbcL gene expression in both maize andArabidopsis.In both plants, accumulation ofrbcL mRNA as well as synthesis of LSU protein were affected. These findings suggest that specific accumulation and binding of the RLSB binding protein torbcL mRNA within BS chloroplasts may be one determinant leading to the characteristic cell type-specific localization of Rubisco in C4plants. Evolutionary modification ofRLSBexpression, from a C3“default” state to BS cell-specificity, could represent one mechanism by whichrbcL expression has become restricted to only one cell type in C4plants.

Background

The highly efficient C4pathway of photosynthetic carbon assimilation is utilized by less than 5% of terrestrial plants, and yet C4plants account for about a fourth of the earth’s primary productivity [1–4].The enhanced photosynthetic capabilities of C4plant species allow them to out-compete more common and less efficient C3species. This is most evident in areas of high temperature and/or low water availability, conditions under which C4plants typically thrive. In spite of their much higher productivity, there are only a few C4plant species utilized as crops for food and biofuel production, the most notable being maize and sugarcane [1–4].Understanding the specialized developmental, molecular, and biochemical processes responsible for C4function is a significant focus of photosynthesis and agricultural research. Agricultural benefits include contributing to the development of non-agricultural C4plants that are more amenable to agricultural usage, understanding mechanisms of plant adaption to extreme arid conditions, and possibly enabling the engineering of C4characteristics into C3crop species [1–5].As a unique developmental system, the specific localization of key photosynthetic enzymes to one cell type, but not in another adjacent cell type within a small localized leaf region, provides a unique opportunity to address molecular mechanisms underlying the selective compartmentalization of gene expression in plants [5,6].

Characteristics common to all C4species include utilization of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPCase) as the initial primary CO2fixation enzyme and production of C4acids by a first stage of reactions, followed by decarboxylation of C4acids, and subsequent re-fixation of released CO2by Rubisco (Calvin cycle) in a second stage. Through the partitioning of Rubisco, C4plants reduce or eliminate the photosynthetically wasteful reactions of photorespiration, thereby enhancing their CO2fixation ability [3,5–9].C4plants typically possess kranz-type leaf anatomy consisting of two distinct photosynthetic cell types, bundle sheath (BS) cells and mesophyll (M) cells [3,5–10].Although some variations have been identified (such as the less common single cell C4photosynthesis), in most C4leaves the BS cells occur as a layer around each leaf vein, with one or more layers of M cells surrounding each ring of BS cells [5–10].This specialized leaf anatomy provides a structural framework that compartmentalizes the two stages of C4carbon assimilation. Together these serve as a “CO2pump” that concentrates CO2within BS cells, where Rubisco is localized. Photosynthesis in kranz-type C4leaves requires the cell-type specific expression of genes encoding certain CO2assimilation enzymes, such as Rubisco in BS cells and PEPCase in M cells [5–7,11].This two-cell compartmentalization and associated cell-type specificity in gene expression does not occur in C3plants, which possess only one photosynthetic cell type, and where the initial CO2fixation enzyme is ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase (Rubisco).

In spite of the clearly defined biological parameters and advantages associated with C4植物(特异性表达,解剖and metabolic modifications, increased nitrogen-use efficiency, adaptability to marginal habitats), molecular processes responsible for C3versus C4photosynthetic gene expression patterns have remained highly elusive for many years. Previous studies have shown that both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation are involved in BS or M cell-specific regulation of C4genes [5–7,11,12].While there are many trans-acting proteins known to be associated with the expression of plastidic- and nuclear-encoded photosynthetic genes at all regulatory levels in both C3and C4plants [5,6,12–17], most of these are not directly implicated in determining BS versus M cell-specific gene expression. Some of the few transcription factors shown to be associated with C4发展pment are members of theGolden 2-like(GLK) gene family [5,11,12].One member of this family,Golden2 (G2)是一个功能的转录监管机构ions primarily within BS cells and affects the overall development of these cells in maize leaves. A paralog of this gene,Glk1, is abundantly expressed in M cells, where it also regulates overall photosynthetic development. Recently, it was demonstrated that a transcription factor encoded by theScarecrow(Scr) gene is associated with the normal development of kranz leaf anatomy, affecting the morphology and plastid content of maize leaf BS cells [18].While each of these transcription factors has significant effects on BS or M cell development, direct regulation of C4photosynthetic gene expression within their respective cell types has not been demonstrated [5,11,12,18].In fact, to date no trans-acting factors have been directly associated with the BS versus M cell-specific regulation of any individual C4gene.

As the principle enzyme of photosynthetic carbon fixation, Rubisco is central to the viability, growth, and productivity of all plants. Understanding regulatory processes responsible for the production of Rubisco specifically within the leaf BS cells of C4plants, and how these processes differ from the “default” C3-type form, is highly significant for understanding the molecular basis of this specialized photosynthetic pathway [5,7,11,12].Rubisco is located within the chloroplasts of all plants, and is composed of eight large (LSU, 51–58 kDa) and eight small (SSU; 12–18 kDa) subunits [7,19,20].TherbcL gene encoding the LSU is transcribed and translated within the chloroplasts. The SSU, encoded by a nuclearRbcS gene family, is translated on cytoplasmic ribosomes as a 20-kDa precursor that is targeted to the plastids. TherbcL andRbcS transcripts and corresponding proteins are highly abundant and coordinately regulated; the two subunits accumulate in stoichiometric amounts within the plastids [5–7,19,20].Rubisco gene expression in C4and C3plants is influenced by many factors, including light, development, cell type, photosynthetic activity, and even pathogen infection [5–7].In addition to transcriptional control, many aspects ofrbcL andRbcS表达式已经被证明是通过控制ugh mRNA processing (degradation or stabilization of transcripts) and regulation of translation. Significantly, many studies have demonstrated that in several dicot and monocot C4species, including amaranth, flaveria, cleome, and maize, post-transcriptional control plays a key role in determining the BS cell-specific expression of genes encoding both Rubisco subunits [5,7].Post-transcriptional control of cell-type specificity forrbcL andRbcS in C4plants is very stringent; even when these genes are ectopically over-expressed in maize, Rubisco accumulation remains highly specific to BS cells [21].

Plastid- and nuclear-encoded mRNAs possess specific cis-acting sequences that mediate their post-transcriptional regulation [6,13–17,22].Cis-acting控制区域内可能发生5′ UTR, the 3′ UTR, or even the coding region of an mRNA. For plastid-encoded mRNAs, where post-transcriptional regulation is the primary regulatory determinant, nuclear-encoded proteins usually interact specifically with 5′ or 3′ UTR sequences to regulate one or more aspects of mRNA metabolism. There are a very large number of nuclear-encoded RNA binding proteins in plastids, reflecting the very large number of complex RNA metabolic processes that occur for each of the 100 or so plastid-encoded transcripts [14,16,17].RNA modifications can include processing of 5′ and 3′ termini, intron splicing, proofreading and editing, as well as regulation of translation and stability. Several classes of RNA binding proteins have been identified and characterized in chloroplasts, many of which are highly specific for unique sequences contained within different plastid-encoded mRNAs [14,16,17,23,24].Among these, the most predominant are the pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) family of RNA binding proteins, with about 450 members in higher plants [16,17,25].One PPR protein has been shown to define 5′- processing ofrbcL mRNA [15].

This current study contributes a new member to the list of plastid-targeted RNA binding proteins that affect gene expression in chloroplasts, in this case through its selective interaction withrbcL mRNA. The RBCL RNA S1-BINDING DOMAIN protein (RLSB) was isolated from chloroplasts of a C4根据其abilit affinity-purification植物y to bindrbcL mRNAin vitro.This protein, encoded by theRLSBgene, is present and highly conserved among a wide variety of plant species, contains a conserved S1 RNA binding domain, and a plastid transit sequence. We show here that RLSB affectsrbcL gene expression within BS chloroplasts of C4maize (Zea mays), as well in C3Arabidopsis(拟南芥) chloroplasts. Mutation or silencing ofRLSBled to clearly observable changes in levels ofrbcL mRNA and LSU protein accumulation, with many associated developmental effects. This is the first cell-type specific regulatory factor to be implicated in the regulation of an individual photosynthetic gene in a C4plant, its accumulation correlating tightly with the BS-specific expression of the plastidicrbcL gene that it regulates. This strong correlation suggests that modifications ofRLSBgene expression from the “default” C3pattern to C4-type BS cell-specificity, and associated cell-type specific localization ofrbcL expression, might represent one evolutionary process enabling C4expression patterns in plants that utilize this specialized pathway for photosynthetic carbon assimilation.

Results

Isolation of anrbcL mRNA binding protein from chloroplasts of a C4plant

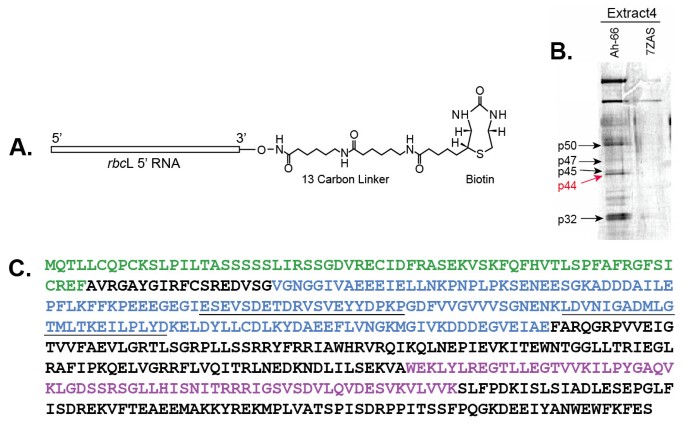

Our earlier studies identified four sites of highly specific RNA-protein interactions at the 5′ region ofrbcL mRNA in plastid extracts from the C4dicot amaranth [26].These were found only in light-grown plants, when Rubisco synthesis occurred, and not in etiolated plants, when Rubisco synthesis did not occur. We hypothesized that RNA-protein interactions such as these might be involved in regulating BS cell-specificrbcL gene expression, as well as light-mediated regulation, in the leaves of C4plants. Two types of RNA “bait” molecules were used for affinity purification of chloroplast proteins that specifically interact withrbcL 5′ RNAs [26]; anin vitro-transcribed RNA corresponding torbcL 5′ RNA of the C4dicot amaranth, a region previously shown to interact with plastidic proteinsin vivo(beginning at the 5′ end of the processedrbcL mRNA at −66 and extending to +60 in the coding region), and a control 7Z-AS RNA, a yeast viral 3′ UTR of similar size and AU content [26,27].These transcripts were biotin-tagged at the 3′ end to allow binding of the RNA to streptavidin magnetic beads (Figure1A). The 5′ RNA-biotin-streptavidin beads were incubated with plastid extracts prepared from leaves of the C4plant amaranth, using preparatory and binding conditions previously optimized for these leaves [26].The bead-bound RNA-protein complexes were washed and isolated by magnetic separation. Figure1B shows affinity purified plastid proteins after incubation withrbcL or control RNAs, separated and visualized by SDS-PAGE.

Isolation and characterization of a plastid-targeted mRNA binding protein. A.rbcL 5′ UTR probe used for affinity purification of RNA binding proteins from plastid extracts. This probe contained a 12 carbon linker and biotin at the 3′ end for attachment to streptavadin magnetic beads.B.BiotinylatedrbcL and control RNAs (7ZAS, is a yeast viral UTR of similar length and AU content) incubated with plastid extracts. RNA-protein complexes were “fished” from the extracts using streptavadin magnetic beads, and then analyzed using SDS-PAGE (10% gel). Bands were excised from this gel and used for identification by Maldi-Tof/amino acid sequence analysis. Red arrow shows the position of the p44rbcL mRNA binding protein (now designated RLSB).C.Diagram of RLSB ortholog ofArabidopsis.Maldi-Tof mass spectrometry/amino acid sequence analysis (Custom Biologics, Toronto, CA), and comparisons of peptide sequences with theArabidopsisand other plant databases, identified one of the purified proteins (p44, red arrow in1B) as having properties of interest, with a plastid transit sequence and a conserved RNA binding domain. Green = plastid transit sequence (identified using (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/).Purple = conserved S1 RNA binding domain. Blue = 149 aa region expressed inE. coliused for affinity purification of p44 (RLSB) antibodies. The 447 nt region encoding this peptide sequence was also used for production of an RNA silencing vector in pHannibal. Underlined sequences within the blue region were used for production of peptide antibodies; the second underlined sequence (bold) also corresponds to a conserved 23 aa tryptic peptide identified in the purified amaranth protein that was identical in theArabidopsisprotein, and highly similar in orthologs from many other plant species (Additional file1: Figure S1 and Additional file2: Figure S2).

At least six distinct affinity-purified proteins were specifically captured withrbcL 5′ RNA, and not with the control viral RNA, ranging in size from 30–70 kDa (Figure1B). Analysis of tryptic peptide sequences using Maldi-Tof mass spectrometry (Custom Biologics, Toronto, CA) indicated that one of the purified proteins (p44, red arrow in Figure1B) had similarity to proteins in the database containing a plastid transit sequence and a conserved S1 RNA binding domain (Figure1C, Additional file1: Figure S1). Taken together, these characteristics identified p44 as a potentialrbcL-mRNA binding protein in chloroplasts. This protein, now designated as RLSB, was selected for further analysis. The sequence and characteristics of theArabidopsisortholog are indicated in Figure1C.

Highly similar orthologs of the RLSB protein were identified in more than 15 plant species including dicots, monocots, C3and C4species. This includesBienertia sinuspersici(Gerald Edwards, personal communication), a dicot plant species that utilizes a unique single-cell form of C4photosynthesis [10].Comparative alignments of representative protein sequences are shown in Additional file1: Figure S1 and Additional file2: Figure S2. Overall similarities among the plant species examined range from 60% for maize-Arabidopsis, to 70% for maize-rice, and 90% for maize-sorghum. All of these proteins have putative plastid-targeting sequences. RLSB appears to be encoded from a single copy gene in all of the species examined.

RLSB is specific to BS cells in C4leaves

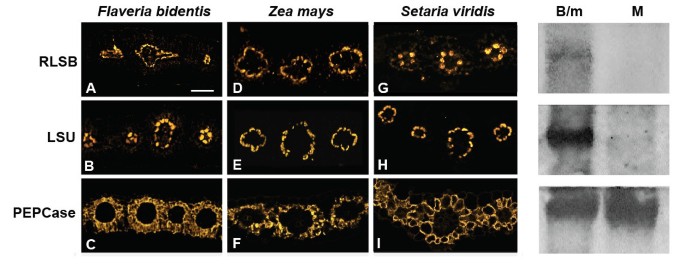

The binding affinity of RLSB torbcL mRNA in extracts from C4chloroplasts presented the possibility that this binding activity might be associated withrbcL regulation within BS cells. If RLSB is in fact closely associated with activerbcL gene expression, then it would be expected that this RNA binding protein, like Rubisco, would also show specificity to BS chloroplasts in the mature leaves of Kranz-type C4plant species. Immunolocalization analysis was performed with three C4species shown in Figure2; the dicotFlaveria bidentis(Figure2column 1; 3A, 3B, 3C), the monocot maize (Figure2column 2; 3D, 3E, 3F) and the monocotSetaria viridis(Figure2column 3, 3G, 3H, 3I). In the leaves of each of these C4species, RLSB (Figure2top row: 3A, 3D, 3G) co-localized with Rubisco LSU (Figure2middle row; 3B, 3E, 3H) specifically within chloroplasts of the leaf BS cells. The sections used for Figure2were all taken from mature leaves (midway between the base and tip) of the indicated plant species, reacted with the primary and secondary antisera indicated, and captured using confocal imaging. Note that inF. bidentis, the RLSB/LSU containing chloroplasts were at the centripetal position within the BS cells (adjacent to the vascular centers), as is characteristic for this C4dicot [28].在玉米和S. viridis, the BS chloroplasts were at the centrifugal portion (away from the vascular center), as expected for these C4monocots [28].Very low levels of 564–577 nm emission were also observed in M cell chloroplasts of sections reacted with RLSB antisera; from this imaging we cannot determine if this was due to very low levels of RLSB accumulating in these cells, or perhaps to background reactions of the affinity-purified RLSB antisera. RLSB does not appear to be an abundant protein, and sensitivity for detection needed to be increased, relative to LSU, for its fluorescent detection. As a control, the MP cell-specific enzyme PEPCase was localized specifically to the cytoplasm of leaf M cells of all three C4species (Figure2bottom row; 3C, 3F, 3I).

Confocal Imaging showing co-localization of RLSB and Rubisco LSU in leaves of three C4plant species.Column 1(A, B, C):Flaveria bidentis, a C4dicot. Column 2(D, E, F): Maize (wild type line B73), a C4monocot. Column 3(G, H, I):Setaria viridis, a C4monocot. Top row(A, D, G): leaf sections from the different C4species were reacted with RLSB antisera. Middle row(B, E, H): leaf sections were reacted with Rubisco LSU antisera. Bottom row(C, F, I): leaf sections were reacted with PEPCase antisera (as an M-specific control). Note the centripetal chloroplast positioning within bundle sheath cells ofF. bidentis, versus the centrifugal positioning in maize andS. viridis.Sections treated with indicated antisera were reacted with R-phycoerythrin(A and B)Alexafluor 584(C to I)secondary antisera and captured using the 40X objective of a Zeiss 710 LSM Confocal microscope.右面板:免疫印迹的可溶性B73玉米叶子protein extracts from mechanically separated cell populations produced using the leaf rolling method. B/m, cell population enriched in BS cells, with some M cells. Equal amounts of protein were loaded into each lane. M, purified M cells. Blots were incubated with antisera against RLSB, LSU, and PEPCase.

To confirm that RLSB does not accumulate in the C4M cells, mechanical separation of BS and M cells from wild type maize B73 was performed using the leaf rolling method [29].This yielded a highly purified population of M cells, as well as a population that was enriched for BS cells but also contained M cells (B/m). Immunoblot analysis clearly demonstrated that RLSB, together with LSU, was present in soluble protein extracts prepared from the B/m cells, but were not detectable in extracts from the purified M cells (Figure2, panels on the right). As a control, PEPCase was very abundant in the purified M extracts, and was also present, at slightly reduced levels, in the B/m cell extracts. It should be noted that the B/m extracts were isolated immediately after rolling out the M cells, without any additional purification steps. We have observed that RLSB degrades rapidly once the leaves have been disrupted; thus this cell population was not subjected to any further purification, leaving a significant amount of M cells remaining in the B/m extracts. The “rolled out” M cell population itself was free of contaminating BS cells, as determined by the lack of LSU in these protein extracts. These findings, together with the immunolocalization analysis, confirm that RLSB is highly specific to BS cells in the leaves of maize and other C4plants.

Specificity of RLSB binding and effects ofrlsb-insertion mutation in the C4monocot maize

Although RLSB was first identified from chloroplast extracts of the C4dicot Amaranth, it’s very strong conservation across many different plant species made it feasible to employ the model C4plant maize (Zea mays) for functional characterization. The numerous genetic and database resources available for maize allowed for mutational, developmental, and molecular analysis of RLSB in a plant with a well-defined genetic background. Some of the resources utilized for this study include those described in [30–33], as well as the Maize Photosynthetic Mutant (PML,http://pml.uoregon.edu/photosyntheticml.html), and The Plant Proteome Database (PPDB; proteomics data for the maize RLSB ortholog can be viewed athttp://ppdb.tc.cornell.edu/dbsearch/gene.aspx?id=674610).

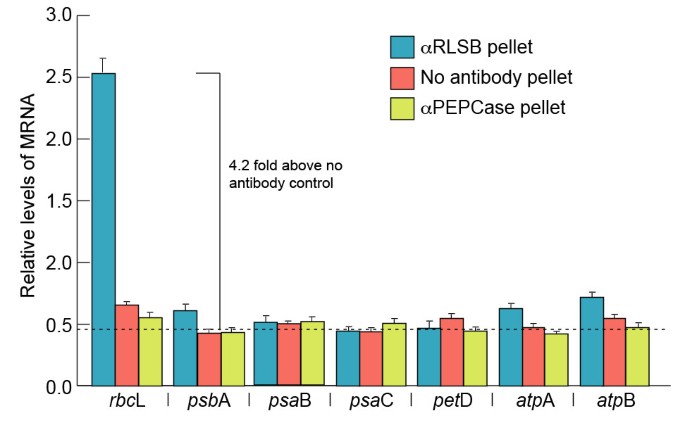

In vitroaffinity purification of RLSB from C4chloroplast extracts provided initial evidence for its selective interaction withrbcL mRNA. To determine if RLSB binds specifically torbcL mRNAin vivo, we used RNA immunopurification with RLSB antisera and quantitative real-time PCR (RIP/qRT-PCR) (Figure3).最近的研究显示增强的reliability and quantitative accuracy of this approach for analyzing specific protein-RNA associations, with a higher degree of enrichment, lower background, and greater dynamic range than previously used methods such as RIP-Chip (for example [34,35]). RLSB was immunoprecipated from chloroplast extracts prepared from leaves of wild type maize line B73 [32].RNA was purified from the pellet fractions, and qRT-PCR was performed using primers forrbcL and, for comparison, the representative plastid-encoded transcriptspsaB,psbA,petD,psaC,atpA, andatpB, as indicated in Figure3.As controls, RIP/qRT-PCR reactions were performed using antisera against cytoplasmic PEPCase, and with no added antisera. All of the qRT-PCR reactions were standardized relative to plastid-encodedrpl2 mRNA (encodes ribosomal protein Rpl2).

Selectivity of RLSB binding to representative plastid-encoded transcripts of maize.Levels of each of the indicated plastid-encoded transcripts were analyzed using RNA immunopurification and real-time quantitative PCR (RIP/qRT-PCR), as described in the text. RNA was extracted from pellet fractions following immunoprecipitations from maize chloroplasts, using antisera against RLSB, or as controls, anti-PEPCase or no added antisera. qRT-PCR was performed using primers for each of the seven transcripts indicated. All mRNA levels were quantified relative to plastid-encoded transcripts of plastid ribosomal protein (rpl2). Results shown are averaged from 2 repeats of 3 independent experiments. The dotted line at 0.48 indicates the average level of amplification from the no-antibody control reactions; this was used as the background value. Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test. For each bar, P values were less than 0.05.

Strong selective association ofrbcL mRNA with RLSB was observed in the maize chloroplast extracts (Figure3).Of the seven plastid-encoded mRNAs examined, only sequences corresponding torbcL mRNA showed high levels of amplification from the anti-RLSB pellet fraction (4.2 fold above background, as determined from the no-added antibody control reactions). Three plastid-encoded mRNAs (psaB,petD,psaC) showed no amplification above background from the immunopurified RLSB pellets. Three other plastid-encoded transcripts (psbA,atpA, andatpB) showed only very slight levels of amplification (0.2 – 0.3 fold above the averaged background value). None of these sequences, includingrbcL, were amplified from control PEPCase immunopurifications, or when no antisera was used (Figure3).It is clear from this analysis thatrbcL mRNA showed significantly greater interaction with RLSB than any of the other representative plastidic mRNAs tested. These findings confirm that the plastid-localized RLSB protein does in fact bind to plastid-encodedrbcL mRNAin vivo, with significant specificity forrbcL mRNA in wild type maize plastids.

The biological significance of RLSB interactions withrbcL mRNA in maize was investigated by making use of Mu transposon insertion mutations within the maize genomicRLSBortholog. The genomic sequence of the maizeRLSBortholog was initially identified (within maize Genomic BAC AC211368.4) using a cDNA sequence accession #BT035293.1 (partial sequence; the full length cDNA is accession #JX650053, Additional file1: Figure S1 and Additional file2: Figure S2). This gene (GRMZM2G087628) is approximately 3540 nucleotides in length, with seven introns (Additional file3: Figure S3). Mu insertions into this gene were identified by screening the maize Photosynthetic Mutant Library (PML) at the University of Oregon (http://pml.uoregon.edu/photosyntheticml.html), using primer sets specific forRLSB和μ转座子边界(见方法)。两个我ndependent lines were isolated and designated asrlsb-1andrlsb-2.Genomic mapping from both ends of the Mu transposon indicates that each line contains a single insert within theRLSBgene, located within the first exon; these occur at positions just 37 nt apart. The insertion inrlsb-1is nearly adjacent to the 5′ splice site of intron 1, positioned 8 nt upstream of the first 5′ intron junction. The insertion inrlsb-2is positioned 45 nucleotides upstream of the first splice junction (red stars in Additional file3: Figure S3). Both Mu insertions occur within a protein coding exon, and would affect the mature RLSB protein within its N-terminal portion, just after the predicted cleavage site for the plastid transit sequence. When homozygous, the phenotype of each line is identical; the leaves start out as virescent-yellow, and gradually begin to green from the tip to the base as they grow and develop (Additional file4: Figure S4, Top panels). The mutants grow more slowly than wild type, so that leaf development is delayed approximately one day. Genetic crosses demonstrate that the two mutants do not complement; most of the experiments presented here were done usingrlsb-1/rlsb-2double mutants.

An analysis of these maize insertion mutants must be undertaken within the framework of the maize leaf developmental gradient. A maize leaf originates and grows outward primarily from an intercalary meristem located at the base of the leaf [36,37].This leads to the development of a linear gradient of cells occurring along the entire length of a growing maize leaf, with younger cells occurring at the lower (basal) regions, and older cells at the outer (towards the tip) regions. Rubisco mRNA and protein accumulation increase along this maize leaf gradient, with the transcripts appearing slightly ahead of their corresponding proteins [5,7].In illuminated maize leaves, Rubisco mRNAs and subunit proteins are specifically localized to BS precursors at their first occurrence, and remain specific to BS cells across the entire developmental gradient.

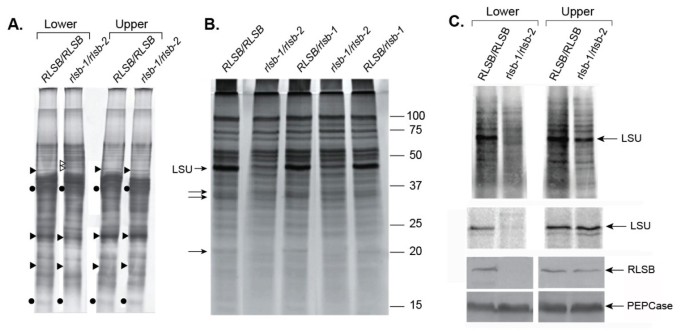

The phenotype of theseRLSBinsertion mutants indicates thatrlsb-1andrlsb-2affect early photosynthetic development, as observed in lower regions of the maize leaf (Additional file4: Figure S4, Top Panels). An overview of total protein accumulation (soluble plus membrane) demonstrated that the overall protein profiles were mostly similar for bothRLSBinsertion mutant (rlsb-1/rlsb-2) and non-insertion mutant (RLSB/RLSB) leaves in the lower leaf regions (lower 1/3 of the leaf, earlier developmental stage), although there were clearly differences in levels for a few proteins bands (Figure4A). Some of these were decreased in lower regions of the mutant leaves, while others were increased (indicated in Figure4A). Most notably, protein bands migrating at the position of the Rubisco LSU and SSU were significantly reduced in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves, relative toRLSB/RLSB.At the leaf upper regions (upper 1/4 of the leaf, more advanced developmental stage), levels of the Rubisco protein bands were elevated, so that identical amounts were present in this portion of the mutant and non-mutant leaves. Similarly, inrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves, protein bands that were altered in lower regions were present at normalRLSB/RLSBlevels in the upper regions. Thus, at this level of analysis, insertion mutants ofRSLBhad different effects on protein accumulation in the lower versus the upper portion of the maize leaf.

Protein accumulation and synthesis inRLSB/RLSBandrlsb-1/rlsb-2double mutant sibling plants.For each panel, proteins were isolated from lower (lower third) or upper (upper third) regions of the first or second emerging leaves (4 – 6 cm in length) from each genotype. PanelA: Equalized amounts of total proteins (soluble plus membrane) isolated from these regions were loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE, and silver stained. The positions of LSU and SSU (solid circles), unidentified proteins reduced in mutant leaf base (solid triangles), and unidentified proteins increased in mutant leaf base (open triangles) are indicated. PanelB: Soluble protein accumulation in lower leaf regions ofRLSB/RLSB, heterozygoteRLSB/rlsb-1, and mutant maizerlsb-1/rlsb-2plants. Positions of the Rubisco LSU, as well as three other soluble proteins affected in the mutant, are indicated (arrows). Note that in this panel, the LSU band is overlapping (and slightly below) another unidentified protein, which somewhat obscures its reduction in the double mutant plants. PanelC, top:In vivosynthesis of total soluble proteins in lower and upper leaf regions. Protein extracts were prepared from leaf disks labeled with35S-met/cys for one hour, as described in Methods. Equalized amounts of labeled extract were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized using a phosphorimager. Position of the LSU is indicated. PanelCmiddle: Immunoprecipitation of LSU from the35S-labeled提取物。路易斯安那州立大学蛋白质immunoprecipitated from equalized amounts of labeled plant extract, separated by SDS-PAGE, visualized and quantitated using a phosphorimager. PanelC, bottom: Immunoblot showing accumulation of RLSB and PEPCase (as a loading control) proteins in lower and upper regions ofRLSB/RLSBandrlsb-1/rlsb-2maize leaves. Equalized amounts of total (soluble plus membrane) proteins fromRLSB/RLSBandrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunostaining using the antisera indicted, as described in Methods.

Reductions in Rubisco LSU levels in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves were more clearly discernible when soluble proteins were analyzed separately (Figure4B). As with total proteins (Figure4A), soluble protein profiles were mostly similar forrlsb-1/rlsb-2mutant andRLSB/RLSBleaves. We detected at least 3 prominent soluble proteins, in addition to the dramatically reduced LSU, that were clearly reduced in lower leaf regions of the mutant plants. Several differences in protein composition were also observed for membrane-bound proteins in the lower leaf regions of mutant plants (not shown). These differences in accumulation of the LSU and other proteins betweenRLSBmutant and non-mutant plants were not observed at the leaf upper regions (not shown). In plants heterozygous for therlsbmutation (RLSB/rlsb-1,RLSB/rlsb-2), accumulation of LSU (and the other indicated proteins) was not affected in either leaf region; the protein profiles for these plants were identical toRLSB/RLSB(Figure4B), demonstrating that the insertion mutant is recessive.

Reductions in LSU protein accumulation were accompanied by reducedin vivosynthesis of the LSU protein in the lower region of the mutant leaves, but not in the upper region (Figure4C, top and middle panels). Incubation of leaf disks fromrlsb-1/rlsb-2andRSLB/RSLBplants with35S-met/cys labeling solution for one hour, followed by isolation of soluble proteins and separation of equalized protein samples by SDS-PAGE, showed greatly reducedin vivosynthesis of the LSU protein in lower regions of the mutant leaves (Figure4C, top panel). While significant differences in synthesis were found for the LSU protein in the lower regions, the majority of proteins observable in the labeled extracts showed no differences betweenrlsb-1/rlsb-2andRLSB/RLSB.This mostly selective reduction in LSU synthesis was not observed in the upper regions. Immunoprecipitation of LSU protein confirmed that LSU synthesis was significantly reduced in the lower regions, but not the upper regions, of therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutant maize leaves (Figure4C, middle panel). As demonstrated by immunoblot analysis using RLSB antisera (Figure4C, bottom panels), greatly reduced levels ofin vivoLSU synthesis in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves correlated very closely with reduced levels of RLSB protein accumulation at these same regions. Comparatively, the upper regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves, and both regions of RLSB/RLSB leaves, all showed much higher levels of RLSB protein accumulation, corresponding with their higher levels of LSU synthesis.

The combined data of Figure4indicate that the accumulation and synthesis of Rubisco LSU protein was delayed, and not completely eliminated, in therlsb-1/rlsb-2maize leaves. The loss or reduction of the RLSB mRNA binding protein was accompanied by reduced production of the Rubisco LSU protein, as well as the other observable effects, only during early leaf development in the lower leaf region. As developmental age advanced along the maize leaf gradient, the effects of this mutation appear to be attenuated, so that in the more developmentally advanced outer leaf regions, LSU synthesis and accumulation reached normal levels.

Immunoblot analysis confirmed the reduced accumulation of both Rubisco LSU protein and RLSB proteins in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2maize leaves. Relative to the same region ofRLSB/RLSBleaves, LSU was reduced approximately 12–15 fold in therlsb-1/rlsb-2plants (Figure5A, top panel, based on phosphorimager software analysis). RLSB was not detectable in therlsb-1/rlsb-2leaf lower regions using these same conditions (Figure5A, middle panel). A digitally enhanced image of the middle panel of Figure5A demonstrates that RLSB did in fact accumulate in the lower leaf regions ofrlsb-1/rlsb-2mutants, but at greatly reduced levels (Additional file5: Figure S5, top panel). In fact, this longer exposure reveals that one of therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutants had slightly higher levels of RLSB, relative to a differentrlsb-1/rlsb-2mutant (compare the second and fourth lanes of Additional file5: Figure S5, top panel). This was correlated closely with slightly higher levels of LSU for this same plant (compare the second and fourth lanes of Figure5A, top panel).

Accumulation of Rubisco LSU and RLSB protein and mRNA in lower leaf regions fromRLSB/RLSBandrlsb-1/rlsb-2maize seedlings.PanelA: Immunoblot showing accumulation of LSU, RLSB, and PEPCase (as a loading control) proteins in lower regions (lower third) ofRLSB/RLSBandrlsb-1/rlsb-2maize seedlings, using the first or second emerging leaves (4 – 6 cm long). Equalized amounts of total (soluble plus membrane) proteins from non-mutantRLSB/RLSBand mutantrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves were separated by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described for Figure4, using the indicated antibodies. PanelB: Real-time quantitative PCR showing relative levels of mRNA accumulation forrbcL andRLSBtranscripts inRLSB/RLSBandrlsb-1/rlsb-2maize seedlings. Quantification of transcript levels was standardized to actin mRNA. Data is averaged for four wild type and four mutant siblings, with three repeats run for each of the plant samples. Note differences in scale for panels showingrbcL andRLSBmRNAs, indicating that these two transcripts accumulate to substantially different levels in both wild type and mutant plants. Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test. For each bar, P values were less than 0.05.

Analysis of mRNA levels using qRT-PCR indicated inRLSB/RLSBmaize leaves,rbcL mRNA was present at much higher levels thanRSLBmRNA (Figure5B). In fact,rbcL transcripts were more than 150-fold more abundant (note the difference Y-axis scales in Figure5B). This difference in relative levels of the two mRNAs may not reflect respective levels of protein accumulation in theRLSB/RLSBmaize leaves, since both RLSB and LSU were easily detected with similar exposure levels of the immunoblots. In lower portions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutant maize leaves, bothrbcL andRLSBtranscript levels were correspondingly reduced (3.5-4.5 fold, respectively) relative to the same region ofRLSB/RLSBleaves (Figure5B). Thus, insertion mutagenesis ofRLSBreduced but did not completely eliminateRLSBandrbcL expression, allowing for low but still detectable levels of both mRNAs to accumulate in lowerrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaf regions. The fact that mRNA levels for both transcripts were reduced in approximate coordination further supports a regulatory connection between RLSB and levels ofrbcL gene expression, involving regulation at the level ofrbcL mRNA accumulation. Furthermore, it is notable that the reduced levels ofRLSBandrbcL transcripts in the lower leaf regions ofrlsb-1/rlsb-2plants were not reflective of actual RLSB and LSU protein accumulation. Most significantly, LSU protein levels were reduced more dramatically thanrbcL mRNA in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutant leaves (12–15 fold versus approximately 4-fold, respectively), suggesting that utilization of therbcL mRNA for translation was also affected by reduced RLSB.

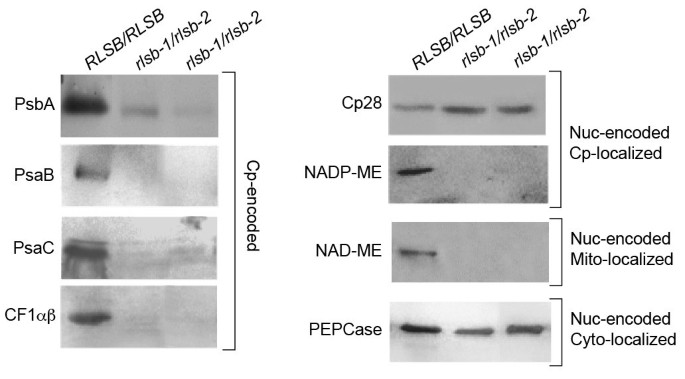

While RLSB shows strong selectivity in binding torbcL mRNA, the effects of therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutation extend beyond this single plastid gene. In addition to LSU, lower leaf regions of the double mutants showed significant reductions in the accumulation of several representative plastid- and nuclear-encoded proteins (Figure6).Also similar to LSU, the reductions described below occurred only in the lower leaf regions ofrlsb-1/rlsb-2plants; in the upper leaf regions, levels had recovered to those ofRLSB/RLSBleaves (data not shown). Decreased RLSB in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves was associated with reductions of five other representative plastid-encoded proteins (Figure6, left panel). PsaB, PsaC, PsbA, and CF1αβ all showedrlsb-1/rlsb-2mutation-associated reductions that were similar to or greater than LSU (compare Figures5A and6).Although there was a trend for some chloroplast-encoded transcripts to have reduced accumulation in therlsb-1/rlsb-2 lower leaf regions (Additional file6: Figure S6A), these reductions were not as dramatic as the protein reductions observed. The most significant reduction occurred forpetD (three-four fold); reductions inpsaB,psaC, andatpB, while statistically significant, were less than two fold. Transcripts forpsbA,atpA andrpl2 showed no significant reductions. Thus, within the chloroplast itself, reductions in RLSB levels were accompanied by consistent drop in levels of many photosynthetic proteins, with variable reductions in levels of different plastid-encoded mRNAs. Plastid-encoded ribosomal RNAs also showed a slight, but not statistically significant, reduction in accumulation in the affectedrlsb-1/rlsb-2 leaf regions (Additional file6: Figures S6B and S6C). Severe reductions in protein accumulation such as these, together with moderate reductions in the accumulation of some mRNAs, might be consistent with a more global effect on plastic translation, as described for maize ribosome assembly mutants [38].However, the lack of any significant effect on ribosomal rRNAs, as would occur be in the case of a general translation mutation, makes it highly unlikely that RLSB would be a member of this class of basic translational regulators. In addition, it is important to consider that, while RLSB is specific to BS cells, all of the other plastid-encoded proteins that were affected would normally accumulate in both BS and M cells, with the photosystem II-associated PsbA protein in fact being most abundant in M plastids [5,11,39].It therefore also highly unlikely that the reduced levels of PsbA, PsaB, PsaC, and CFαβ in therlsb-1/rlsb-2 lower leaf regions could be a direct result of reduced RLSB accumulation, since this protein is not present in M cell chloroplasts in any case.

Accumulation of various plastid- and nuclear-encoded proteins in leaf basal regions ofRLSB/RLSBand insertion mutantrlsb-1/rlsb-2maize seedlings.Equalized amounts of total (soluble plus membrane) proteins from non-mutantRLSB/RLSBand mutantrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves were separated by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described for Figure4, using the indicated antibodies. Cp-encoded, chloroplast-encoded proteins. Note that CF1αβ antisera reacts to both the alpha and beta subunits, which run at the same position on this gel. Nuc-encoded Cp-localized, nuclear-encoded proteins targeted to the chloroplast. Nuc-encoded Mt-localized, nuclear-encoded protein targeted to the mitochondria. Nuc-encoded Cyto-localized, nuclear-encoded protein localized within the cytoplasm.

Most interestingly, therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutation affected two representative nuclear-encoded proteins as well. The C4photosynthetic NADP-ME-dependent malic enzyme (NADP-ME, nuclear-encoded, plastid targeted) was significantly reduced (below detectable levels). Similarly, the non-C4NAD-dependent malic enzyme (NAD-ME, nuclear encoded, targeted to mitochondria) was also greatly reduced (below detectable levels) in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutants (Figure6).In contrast, levels of an RNA binding protein known as CP28 (nuclear-encoded plastid targeted protein [16,40] were not at all affected in therlsb-1/rlsb-2andRLSB/RLSBplants. Similarly, the C4photosynthetic PEPCase (nuclear encoded, cytoplasmic) was not affected in any region of therlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves. The contrasting effects of therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutation on two different nuclear-encoded plastid targeted proteins, Cp28 and NADP-ME, is particularly striking. If this were a direct result of reduced RLSB, or an indirect process inhibiting their import/accumulation due to reduced chloroplast function, then both proteins should have been similarly impacted. Similarly, reductions in a plastidic RNA binding protein would not be expected to directly affect the accumulation of a metabolic protein targeted to the mitochondria.

The multiple levels of analysis presented here provide strong evidence that in maize leaves, reduced accumulation of therbcL mRNA binding protein RLSB leads to corresponding reductions inrbcL mRNA accumulation and LSU synthesis within BS chloroplasts. These findings support a direct effect on post-transcriptionalrbcL gene expression, with an impact on both mRNA stability and translation. Indirect effects resulting from reduced RLSB andrbcL expression in the double mutants extend to proteins that are encoded, synthesized, and accumulate within other cell types and other cell compartments.

RLSB localization and basic “default” function in C3plants

RLSB is highly conserved across a broad range of C4as well as C3plant species (Additional file1: Figure S1, Additional file2: Figure S2). In consideration of this very strong conservation, we hypothesized that RLSB shares a commonrbcL regulatory role in all plants, and may have been recruited from a more basic role in C3species (“default”rbcL regulatory patterns) to function as a cell-specificity determinant in C4plants (more specialized C4rbcL regulatory patterns).Arabidopsis, with its extensive genetic, molecular biology, and genomic resources ([41],http://www.arabidopsis.org), provides an ideal model system for comparative RLSB functional analysis in a plant that utilizes the C3pathway of CO2assimilation [5–7].

Photosynthesis in C3植物主要发生在叶片叶肉细胞s. This general classification of photosynthetic cells makes up the interior of the leaf (between the upper and lower epidermis, excluding vascular cells) and includes the palisade and spongy parenchyma [42,43].In leaf sections ofArabidopsis, confocal fluorescent imaging, superimposed on a DIC image, clearly establishes the co-localization of RLSB and LSU proteins within mesophyll cell chloroplasts (Figure7).低放大倍数的概述immun相似olocalizations indicted that both chloroplast proteins were distributed throughoutArabidopsisleaf mesophyll cell population, with no cell-type preferential or distributional accumulation patterns detected within this population (Additional file7: Figure S7).

Immunolocalization of RLSB and Rubisco LSU proteins in leaf sections of the C3plantArabidopsis.PanelA: Confocal/DICI image ofArabidopsisleaf section reacted with RLSB primary antiserum. PanelB: Confocal/DICI image ofArabidopsisleaf section reacted with LSU primary antiserum.Arabidopsisleaf sections were incubated with the indicated primary antiserum, and then Alexafluor 546 conjugated secondary antibody. Images were captured using the 40X objective of a LSM 710 “in tune” confocal microscope. Fluorescent immunolocalization was combined with bright field DICI to clearly show plastid localization for both proteins. bar = 20 μM.

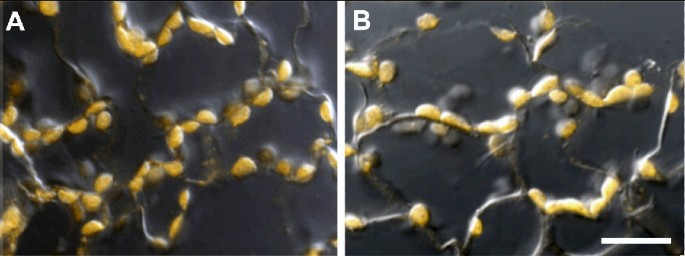

To determine if RLSB is associated withrbcL expression in a C3plant, a 447 bp inverted repeat fragment of theArabidopsis RLSBortholog was expressed and used to induceRLSBsilencing inArabidopsis.Seed from floral-dipped plants were germinated and grown on MS media containing Kanamycin with 3% sucrose. To maintain viability, Kanamycin-resistant plants, which showed very slow growth, were transferred two weeks after germination to MS media containing 8% sucrose without further Kanamycin selection. Six confirmedrlsb-silenced plants were selected for further analysis; all produced nearly identical data. The data sets shown in Figure8were obtained from two of these plants that were found by initial protein analysis to have either the least (rlsb-silenced 1) or most severe (rlsb-silenced 2) reductions in LSU accumulation among the six.

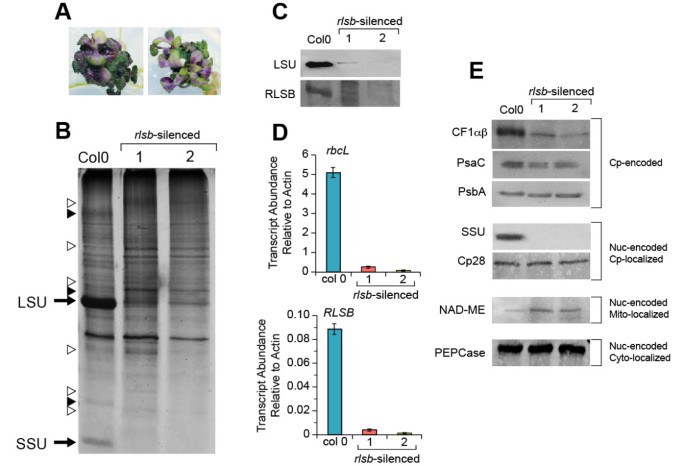

RNA silencing ofRLSBin the C3plantArabidopsis.PanelA: Morphology of tworlsb-silenced plants. 12-week-oldrlsb-silencedArabidopsisgrown on MS media supplemented with 8% sucrose. PanelB: Total soluble proteins isolated from leaves of wild type (Col0) and two representativerlsb-silenced (1 and 2)Arabidopsisplants were separated by SDS-PAGE and silver stained. The positions of LSU and SSU are indicated. Unidentified proteins that were reduced or increased in the silenced plants relative to wild type (open or solid triangles, respectively) are indicated. PanelC: Western blot showing levels of accumulation for LSU and RLSB proteins in leaves from Col0 and tworlsb-silencedArabidopsisplants. Total maize leaf proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunostaining as described in Methods. PanelD: Real-time quantitative PCR showing relative levels of mRNA accumulation forrbcL andRLSBin leaves from Col0 and the tworlsb-silencedArabidopsisplants. Quantification of transcript levels was standardized to actin mRNA. Data is averaged for four wild type and four mutant siblings, with three repeats run for each of the plant samples. Note differences in scale for panels showingrbcL andRLSBmRNAs. PanelE: Western blots showing accumulation levels of additional proteins in Col0 and the tworlsb-silencedArabidopsisplants. Protein extracts used for panelCwere separated by SDS-PAGE and detected with the indicated antibodies as described.Cp-encoded, chloroplast-encoded proteins (note that CF1 alpha and beta subunits run at the same position on this gel), Nuc-encoded Cp-localized, nuclear-encoded proteins targeted to the chloroplast. Nuc-encoded Mt-localized, nuclear-encoded proteins targeted to the mitochondria. Nuc-encoded Cyto-localized, nuclear-encoded proteins localized within the cytoplasm. For all of the protein and RNA samples analyzed in this Figure, equalization for isolation, loading, and analysis was based on using equalized wet weights of starting leaf material.

Plants expressing therlsb-silencing construct were easily discernable by their altered morphologies. These included severely reduced shoot growth, altered shoot morphology (there was no typical leaf rosette organization), and purple coloration of the leaves (Figure8A). The silenced plants did not survive after transfer to soil, and were maintained on the high-sucrose media continuously. The silenced plants rarely produced bolts or flowers, and did not survive longer than 30 days. Seed from control (non-transformed) Col0 plants, germinated and grown using the same 3% and 8% sucrose-media and growth conditions, but without the initial Kanamycin selection, did not show any of these silencing phenotypes (Additional file4: Figure S4, bottom panels). The size of therlsb-silenced plants varied between the lines, showing size reductions in overall shoot growth of approximately one-third to one-fourth by 6 to 8 weeks after germination, when compared to Col0 grown on the same media under the same sterile conditions. Root growth on the transgenic plants was also impeded, but to a lesser extent.

Observations of total soluble protein accumulation revealed striking reductions in levels of protein bands corresponding to the Rubisco LSU and SSU in therlsb-silenced plants (Figure8B). There were also a few easily observable changes in several unidentified proteins that either increased or decreased in the silenced plants, relative to the controls (Figure8B). Aside from these, overall patterns of protein accumulation were mostly similar in silenced and wild type Col0 plants. To better understand the levels, range, and specificity of proteins affected by silencing ofRLSB, immunoblot analysis was used to check for any possible changes in a range of representative proteins.

Using antisera against LSU and RLSB, dramatic and corresponding reductions in the accumulation both proteins were observed in therlsb-silenced plants, relative to wild type Col0 (Figure8C, first and second panels). Levels of LSU protein accumulation varied somewhat between different silenced plants (compare the second and third lanes of Panel 7C), but were always considerably lower than in wild type (25–50 fold forrlsb-silenced 1 and 2, respectively, based on digital imaging analysis). Longer exposures of the immunoblot in the top panel showed that very low levels of LSU protein did in fact accumulate in the silenced plants (Additional file5: Figure S5, bottom panel). Although RLSB protein was not detected in any of the silenced plants, very low levels of accumulation cannot be ruled out. Detection of this protein by immunoblot required longer exposures even in wild typeArabidopsis(the blot in the second panel of Figure8C required longer exposure time than the other panels), possibly due to lower steady-state levels of accumulation/stability, or reduced sensitivity of RLSB antibody, relative to LSU.

Analysis of mRNA levels using qRT-PCR indicated that in wild type Col0 plants,rbcL mRNA was considerably more abundant thanRLSBmRNA (55-fold more abundant, note the difference in y-axis scales in Figure8D). Although such dramatic differences in transcript levels may not be reflective of final protein accumulation, the data of Figure8C and8D do indicate that the RLSB may be produced or accumulate at lower levels than LSU in plastids of wild typeArabidopsis.In comparing changes in relative levels ofrbcL andRLSBtranscripts in wild type andrlsb-silenced plants, it is apparent that silencing led to greatly and correspondingly reduced levels of accumulation for both transcripts (Figure8D). In the silenced plants, both mRNAs showed correlating ratios of reduction, with approximately 25–50 fold lower levels (rlsb-silenced 1 and 2, respectively), relative to wild type for bothrbcL andRLSB.The fact that both of these transcripts were detectable, even at greatly reduced levels, indicates thatRLSBexpression was not completely silenced. The finding thatrbcL mRNA and LSU protein levels were reduced in close coordination with levels of silencing forRLSBprovides support for our hypothesis that this S1-RNA binding protein affectsrbcL gene expression, at least in part, at the levels of translation and mRNA accumulation.

Of four other representative plastid-encoded proteins examined in therlsb-silencedArabidopsis,chloroplast coupling factor 1(CF1αβ alpha and beta subunits) showed an intermediate silencing-associated reduction in accumulation (less than that of LSU, approximately 10 – 12 fold), while PsaC and PsbA levels were mostly unaffected (Figure8C). As expected, immunoblots confirmed that the nuclear-encoded, plastid targeted SSU was also greatly reduced in the silenced lines; this methodology did not detect any SSU protein in the silenced plants. Another nuclear-encoded, plastid-targeted protein, the Cp28 RNA binding protein [16,40], was not affected by silencing ofRLSB.Two nuclear-encoded cytoplasmic proteins, PEPCase and NAD-dependent malic enzyme (NAD-ME), showed no reductions in the silenced plants (Figure8C). In fact, NAD-ME showed a slight increase in abundance (approximately 3-fold) relative to control plants.

Taken together, the data shown in Figure8indicate thatRLSBgene expression was greatly reduced, but not completely eliminated, due to incomplete gene silencing in theseArabidopsislines. This resulted in a corresponding reduction in levels ofrbcL mRNA and LSU protein, providing strong evidence that the nuclear-encoded RLSB protein is necessary for normal levels ofrbcL gene expression in the chloroplasts of this C3plant.

Confirming evidence that RLSB affectsrbcL expression was obtained from studies that were initiated usingArabidopsislines containing a T-DNA insertion within the At1g71720 locus that encodes the RLSB protein in this plant. The data shown in Additional file8: Figure S8 summarizes findings from one of these lines (SALK_015722, identified through TheArabidopsisInformation Resource TAIR and obtained throughArabidopsisBiological Resource Center (ABRC;http://abrc.osu.edu) [41].本文分别插入在这条线内注册ion encoding the S1 RNA binding domain, which would be expected to eliminate the binding ability and function of this protein. Plants homozygous for the T-DNA insert in this line were never recovered. All of the heterozygote siblings from line SALK_015722 showed reduced accumulation ofrbcL-encoded Rubisco LSU protein (Additional file8: Figure S8A), when compared to Col0 plants, or sibling plants that segregated out the insert (Additional file8: Figure S8B). Note that in these At1g71720 insertion mutants, levels of LSU were not reduced as dramatically as in therlsb-silenced plants (approximately 5-fold, as opposed to 25–50 fold in therlsb-silenced plants). Also unlike therlsb-silencedArabidopsis, levels ofrbcL mRNA were not reduced in any of these lines (Additional file8: Figure S8C), suggesting that in this case, translation ofrbcL mRNA, but not mRNA stability, was impeded. It should be noted that these lines did not stably maintain the T-DNA insert, so plants heterozygous for the insert in the At1g71720 locus were recovered only rarely, and then not at all after four self-pollinated generations. For this reason, these T-DNA insertion lines were not extensively analyzed, and our focus shifted to therlsb-silenced lines for the more detailed analyses of RLSB function inArabidopsisas presented in Figure8.

Discussion

The RLSB binding protein in maize and other plants

Findings presented here indicate that RLSB is a nuclear-encoded S1-domain RNA binding protein that interacts with plastid-encodedrbcL mRNA, thereby activating or enhancingrbcL gene expression. RLSB was purified from chloroplasts based on its specific binding to the 5’ region ofrbcL mRNAin vitro.The purified protein is highly conserved among a wide variety of monocot and dicot C3and C4plant species, and contains a predicted plastid transit sequence. It is localized to chloroplasts in both the C3dicotArabidopsisand the C4monocot maize. Most significantly, in the leaves of all three C4species examined, it co-localized with Rubisco only within BS cell chloroplasts, corresponding with the specific cellular compartmentalization of Rubisco in C4leaves.

RLSB is an S1 binding domain protein in the same category as the ribosomal protein S1, from which this class is named [44].Other than its conserved binding domain, RLSB is a unique chloroplast protein; it shows very little overall identity with known examples of plastidic ribosomal S1 proteins, including those from spinach (AAA34045.1), cucumber (ABK55725.1), rice (ABF95618.1) orChlamydomonas(CAE51165.1). Stretches of amino acids spanning the S1 RNA binding domain display 33% - 73% maximum identity with gaps, depending on the species comparisons. However, outside of this conserved domain there are no extensive regions of significant similarity between the plastidic RLSB and ribosomal S1 proteins. RLSB orthologs inArabidopsis, maize, and other plant species used for our comparisons (Additional file1: Figure S1, Additional file2: Figure S2) appear to be unique members of the S1 class of RNA binding proteins, distinct from other known proteins of this class, and from other known plastidic RNA binding proteins.

The S1 binding domain that distinguishes this protein is found in a large number of RNA binding proteins [44].The S1 binding domain structure is very similar to that of cold shock proteins, and appears to be derived from a very ancient class of nucleic acid binding proteins. While these proteins are known to be widespread among a variety of organisms, there is very little known about the function of proteins that contain this domain. In higher plants, some non-ribosomal proteins known to possess S1 domains include the plastidic polynucleotide phosphorylase [45核糖核酸酶E / G -type endoribonuclease [46], and exosome subunit AtRrp4p [47].Examples of other known S1-domain proteins include transcription factor NusA and polynucleotide phosphorylase in bacteria [48,49], and a nucleic acid binding protein of unknown function in humans [50].

Analysis by immunolocalization as well as mechanical cell-separation demonstrated the BS-specific localization of RLSB in leaves of the C4plant maize. Maize proteomic data localizes RLSB to the chloroplast nucleoid, where transcription is coupled to post-transcriptional RNA processing and translation [51];http://ppdb.tc.cornell.edu/dbsearch/gene.aspx?id=674610.这是一个非常全面的数据库,不过我t does not provide information about the occurrence of RLSB in separated BS or M cells. This information is provided for other C4proteins (for example, see Rubisco LSU,http://ppdb.tc.cornell.edu/dbsearch/gene.aspx?id=652357).Protocols for separating BS and M cells have been shown to affect the accumulation of some BS and M proteins in C4plants (for example, [52]), and it is possible that RLSB was not present when the separated BS and M extracts were used for proteomic analysis. The absence of RLSB from the separated cell populations might be related to our observation that this protein does not appear to be stable in the disrupted BS cells after separation by leaf rolling. This is why the BS-enriched strands were used immediately for protein isolation, without further purification of the BS strands after the M cell “roll out” (Figure2).

This current study is focused on RLSB protein, and not its mRNA. Still, it is important to mention that our experimental findings of BS specificity for RLSB protein in maize might not appear to be in agreement with data contained in two recent maize transcriptome databases (30, 33), which have analyzed mRNA populations in separated BS and M cells. For example, using the B73 C3/C4 transcriptome web browser tool (http://c3c4.tc.cornell.edu/search.aspx) of Li et al. [30] forRLSB(GRMZM2G087628) mRNA, only a portion of the transcript sequence is indicated as being present in both the laser capture microdissection (LCM) leaf tip (mesophyll) and LCM leaf tip (bundle sheath) graphs from that database. The first four exon sequences from the 5′ portion (more than half of the full-length mRNA sequence) are missing from these two graphs; only 3′ exon sequences are indicated as being present in the two separated cell types. This might imply an anomaly forRLSBmRNA in the separated cell populations. In contrast, transcriptome graphs from leaf tip and leaf base (cells not LCM separated, combined transcripts from both cell types) show all eight exon sequences present. In stronger contradiction to our RLSB protein data, the transcriptome database of Chang et al. [33] (based on enzymatic digestion-mechanical separation instead of LCM) actually indicates that GRMZM2G087628 transcript sequences are significantly more abundant in M cells than in BS cells (>13 fold). These databases are both very comprehensive and useful tools for analysis of C4gene expression. However, for reasons stated above, it is possible that the integrity/cell specificity for this particular mRNA was not maintained during the cell separation protocols utilized for those databases, leading to conflicting findings. Alternatively, post-transcriptional control ofRLSBmRNA processing, stability, or translation could be involved in determining cell-type specificity for the RLSB protein, as has been found for genes encoding Rubisco and many other C4proteins [5–7,11].An analysis ofRLSBmRNA transcription, accumulation, and stability in BS and M cells is currently under investigation and will be included in a separate study.

InArabidopsis, the eFP browser (http://bbc.botany.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi) shows a strong correlation in the timing of expression of mRNA accumulation, primarily in photosynthetic (green) plant tissues, forRLSB(At1g71720) (http://www.bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi?dataSource=Developmental_Map&modeInput=Absolute&primaryGene=At1g71720%20&secondaryGene=None&modeMask_low=None&modeMask_stddev=None) andrbcL (Atcg00490) (http://www.bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi?dataSource=Developmental_Map&modeInput=Absolute&primaryGene=Atcg00490%20&secondaryGene=None&modeMask_low=None&modeMask_stddev=None), providing additional correlative evidence for RLSB andrbcL interaction. The online expression profiles indicate that inArabidopsis,an exception to theRLSBandrbcL correlation occurs in dry seed, where transcripts forRLSB, but notrbcL, occur in abundant amounts. Rubisco mRNAs and enzymatic activity have been found to occur transiently during very early seed development, dropping off at later stages [53,54].During seed development inBrassica napus, Rubisco activity, independent of the calvin cycle, has been shown to enhance carbon acquisition, which promotes the formation of seed oil [55].In addition, mRNA accumulation and translation of the LSU and SSU proteins can occur very soon after germination [5,8,56–58].Thus, there is a potential role for RLSB during seed development, and possibly for enabling the rapid onset of early Rubisco synthesis during germination.

RLSB binding activity, andrbcL gene expression in maize andArabidopsis

RLSB was isolated based on its ability to bindrbcL 5′ RNA but not a control RNAin vitro, indicating at least some specificity for the Rubisco chloroplast transcript. Further analysis by RIP/qRT-PCR extended these initial findings by demonstrating prominent selective binding of RLSB torbcL mRNA, but not other plastid-encoded transcripts,in vivo.Thein vivoassay also revealed the possibility of much weaker interactions withpsbA,atpA, andatpB mRNAs, all of which accumulate in both BS and M plastids of maize leaves, withpsbA actually being far more abundant in M plastids [39,59].The fact that RLSB was not detectable in maize M cells would suggest that this greatly reduced binding activity to mRNAs other thanrbcL might not be biologically significant, likely caused by background binding within the chloroplast lysates. The data presented here cannot rule out the possibility that RLSB may in fact have additional target RNAs within BS chloroplasts that were not identified because they were not included in this assay. Higher plant chloroplast genomes can encode over two hundred protein-encoding and non-coding mRNAs [6,60,61].genomics-based寻找额外的mRNA焦油gets in maize andArabidopsisplastids is required to definitively identify the full range of RLSB binding specificity, and is currently in progress. However, the finding that RLSB interacted preferentially withrbcL mRNA, and only weakly or not at all with any of the other six plastid-encoded mRNAs examined, indicates a very high degree of binding selectivity.

In maize, the developmentally early lower regions ofrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves displayed greatly lowered RLSB protein accumulation, together with reductions in levels ofrbcL mRNA, as well as in the accumulation and synthesis of the LSU protein. All of these mutation-associated changes (rbcL mRNA, LSU accumulation and synthesis) correlated very closely in these same lower leaf regions. These parameters all recovered to normal non-mutant levels in the developmentally advanced outer regions. Thus, in maizerlsb-1/rlsb-2mutants, RLSB production, and associated LSU synthesis/accumulation, were delayed (but not eliminated) along the maize leaf developmental gradient. In comparison,rlsb-silencing in the C3Arabidopsisplant led to greatly reduced levels ofRLSBmRNA and its encoded protein throughout the entire length of the leaf, relative to wild type Col0. Throughout the same silenced leaves, strongly correlating reductions inrbcL mRNA and LSU protein also occurred.

When comparing the effects of reduced RLSB expression in the silencedArabidopsisand transposon-mutagenized maize, some similarities and significant differences become apparent. In both the C3and the C4experimental plant systems, reductions in levels ofRLSBandrbcL mRNA, as well as their encoded proteins, occurred in approximate coordination (Figures5and8).Such findings support a common regulatory connection between RLSB and levels ofrbcL gene expression in both plants. As inRLSB/RLSBmaize, Col0Arabidopsisleaves had more abundant levels ofrbcL mRNA thanRSLBmRNA (Figures5B and8D, note the difference Y-axis scales). However, inArabidopsisthis difference was less pronounced (25–50 fold, relative to more than 150-fold in maize). In maize, insertion mutagenesis did not completely eliminateRLSBexpression, allowing for reduced but detectable levels ofrbcL expression in lowerrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaf regions. Silencing ofRLSBinArabidopsisresulted in much more dramatic effects than in the maize mutants, but very low levels ofRLSBandrbcL expression were still detectable in these plants.

LoweredRLSBexpression in both plants led to corresponding coordinated effects on levels ofrbcLmRNA accumulation, LSU synthesis (in maize), and LSU accumulation. Lowered levels ofrbcL mRNA inRLSB-silencedArabidopsisandrlsb-1/rlsb-2maize mutants suggest that RLSB is required for the stabilization of these transcripts. However, the finding that LSU synthesis and accumulation were reduced much more dramatically thanrbcL mRNA inrlsb-1/rlsb-2lower leaf regions (approximately 4-fold for mRNA, 15 fold for protein), and reduced LSU accumulation was not accompanied by lowerrbcL mRNA in theArabidopsisAt1g71720-insertion heterozygotes, suggests a role in translation as well. Similar to the data of Figure5B, an earlier study also found thatrbcL mRNA accumulation in maize was reduced approximately four-fold in response to a decrease in translation [38].In fact, many studies have confirmed a close relationship between the processes of transcript stabilization and translation in chloroplasts, with both processes regulated by RNA binding proteins [5,16,17,24,62].Taken together with thein vitroandin vivobinding data, evidence presented here clearly implicate RLSB as a key determinant ofrbcL gene expression in the chloroplasts of all photosynthetic leaf types in C3Arabidopsis, and exclusively in the BS chloroplasts of C4maize. The tight correlative changes associated with loweredRLSBexpression (confirmed by multiple levels of analysis) are strongly indicative of a regulatory link between RLSB andrbcL gene expression, with RNA binding possibly implementing an effect at the level of RNA metabolism (rbcL mRNA translation and stability).

A significant difference between the two plant systems was apparent when comparing the effects of reduced RLSB on proteins other than LSU (Figures6and8E). Although there were no effects on nuclear-encoded PEPCase or CP28 in either plant, effects on other representative plastid- and nuclear-encoded proteins differed considerably. In contrast to maize, reduced RLSB inArabidopsiswas not associated with any changes in the accumulation of the plastid-encoded PsaC or PsbA (components of PSI and PSII, respectively), while reductions in CF1αβ were considerably less pronounced. The nuclear-encoded NAD-ME actually increased in therlbs-silencedArabidopsis, as opposed to the strong decrease observed in the maize mutants. It might be expected that any direct effects of reducing this highly conserved S1 binding protein would be consistent between the C3and C4plants, with shared reductions in LSU being distinctly prominent. However, with regards to effects on other proteins, variations between two photosynthetic systems proteins were clearly evident.

Other effects of reducedRLSBexpression

In maize, reduced and delayed RLSB and LSU production inrlsb-1/rlsb-2lower leaf regions was associated with strong decreases in the accumulation of several additional plastid- and nuclear-encoded proteins. Reductions in levels of the nuclear-encoded SSU protein were expected, since the expression, synthesis, and assembly of the two Rubisco subunits are tightly coordinated [7,20,63].It was, however, surprising to observe such strong reductions in other representative plastid- and nuclear-encoded proteins. Like LSU, these all increased to normal levels in outer regions of the leaf. Developmental increases inrbcL andRLSBexpression were also associated with basipetal recovery of the virescent phenotype inrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaves. Multiple effects similar to those in therlsb-1/rlsb-2 mutants have been associated with other maize mutations that affect general regulators of plastidic gene expression, such ascpsandhcf[38].However, there are several characteristics and observations that distinguish therlsbmutants from the general regulator mutants. First and most importantly, findings presented here clearly demonstrate that RLSB is strictly confined to chloroplasts within the maize leaf BS cells. However, most of the affected plastid-encoded proteins actually accumulate equally, or even more abundantly, within M cell chloroplasts of wild type maize leaves [39,59].A general regulator that is specifically localized within BS chloroplasts could not directly affect translation of mRNAs in M chloroplasts. Second, while severe reductions in PsaC and PsbA were associated with decreasedRLSBexpression and LSU production in the lower leaf regions ofrlsb-1/rlsb-2 maize mutants, these same proteins were not affected at all in therlsb-silencedArabidopsis, even in the presence of much more severe RLSB and LSU decreases. A highly conserved general regulator of ribosome assembly would be expected to have the same function and produce analogous effects in both plants. Third, there was no significant decrease in plastid ribosomal RNA levels observed for therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutants, indicating that, unlike thecpsandhcfmutants, ribosome accumulation was not affected. Fourth, in contrast to thecpsandhcfmutants that affect only translation, therlsb-1/rlsb-2mutants showed variation in accumulation levels for several plastid mRNAs as well. Fifth, unlike the general plastidic regulators, the effects ofrlsb-1/rlsb-2mutants were not confined to the chloroplasts; levels of two nuclear-encoded proteins were also significantly reduced, including the NADP-ME that was not affected incpsorhcfmutants [38].It is clear that RLSB shows selective binding torbcL mRNA in affinity purification and in RIP/qRT-PCR analysis; binding to other plastid-encoded transcripts, including those with severely reduced protein accumulation in lowerrlsb-1/rlsb-2leaf regions, was minimal or did not occur. These distinguishing characteristics, together with the BS-specific localization of RLSB, its selective binding torbcL mRNA and clear effects on LSU production, confirm the distinct identity of this protein, functionally separating it from the previously identified plastid ribosome assembly mutants of maize.

All of the recoveredrlsb-silencedArabidopsishad multiple developmental abnormalities, including dark purple leaves, reduced leaf size, and impaired root development. They did not produce bolts or flowers, and died after 30 days. These effects were not observed on non-transformed plants grown without selection on the same medium under the same conditions (Additional file4: Figure S4, bottom panels). These effects were also not observed in any of the heterozygous At1g71720-insertion plants, which showed much less severe reductions in LSU accumulation. While anthocyanin production is known to increase whenArabidopsisplants are grown in the presence of high sucrose [64,65], leaves of therlsb-silenced plants had much darker pigmentation than leaves of non-transformed plants grown on the same high-sucrose media. The very high levels of purple pigmentation is an indicator of a stress response [64].It is clear that in this C3plant species, severely lowered levels of RLSB not only leads to greatly reduced production and accumulation of Rubisco, but also affects many other aspects of growth and development.

The more severe reduction inRSLBexpression inrlsb-silencedArabidopsiscorrelated with a much greater effect on LSU mRNA and protein accumulation than inrlsb-1/rlsb-2 maize leaves. Based on the sampling of proteins shown in Figure8, it appears that the greatly reducedRLSBexpression did not result in a strong general cessation/decrease of proteins other than LSU and its associated SSU in this C3plant. Like increased anthocyanin, increases in the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial enzyme NAD-ME are often occur in response to plant stress [5,66,67], in this case possibly brought about by growth/developmental challenges in the silencedArabidopsis.

Several studies have also demonstrated that plants with reduced Rubisco are recoverable and viable [63,68–72].In some cases these plants can have their growth enhanced by supplementing atmospheric CO2[69], or for therlsb-silencedArabidopsisdescribed here, by adding additional carbon source to the media to facilitate more heterotrophic growth. In contrast to the multiple associated effects reported here for therlsb-1/rlsb-2 mutants, a recent study with a different maize mutant showed that greatly reduced Rubisco accumulation, caused by a defect in the assembly factor RAF1, did not show any effects on other plastid-encoded proteins [72].It may be important to consider that separate analysis of lower and upper leaf regions were not reported in that study, and the developmental stages analyzed might not be directly comparable to those used here. However, the finding that greatly reduced Rubisco within theraf1 mutant leaves had no observable effect on any other plastid-encoded proteins represents a clear difference from the effects observed in lower regions of therlsb-1/rlsb-2 leaves. It could be relevant that RLSB impacts the earliest step of LSU synthesis, whereas RAF1 affects Rubisco accumulation at the much later step of Rubisco assembly/degradation.