- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Silencing ofNicotiana benthamiana Neuroblastoma-Amplified Genecauses ER stress and cell death

BMC Plant Biologyvolume13, Article number:69(2013)

Abstract

Background

Neuroblastoma Amplified Gene(NAG) was identified as a gene co-amplified with the N-mycgene, whose genomic amplification correlates with poor prognosis of neuroblastoma. Later it was found that NAG is localized in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and is a component of the syntaxin 18 complex that is involved in Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport in human cells. Homologous sequences ofNAGare found in plant databases, but its function in plant cells remains unknown.

Results

Nicotiana benthamania Neuroblastoma-Amplified Gene(NbNAG) encodes a protein of 2,409 amino acids that contains the secretory pathway Sec39 domain and is mainly localized in the ER. Silencing ofNbNAGby virus-induced gene silencing resulted in growth arrest and acute plant death with morphological markers of programmed cell death (PCD), which include chromatin fragmentation and modification of mitochondrial membrane potential. NbNAG deficiency caused induction of ER stress genes, disruption of the ER network, and relocation of bZIP28 transcription factor from the ER membrane to the nucleus, similar to the phenotypes of tunicamycin-induced ER stress in a plant cell.NbNAGsilencing caused defects in intracellular transport of diverse cargo proteins, suggesting that a blocked secretion pathway by NbNAG deficiency causes ER stress and programmed cell death.

Conclusions

These results suggest that NAG, a conserved protein from yeast to mammals, plays an essential role in plant growth and development by modulating protein transport pathway, ER stress response and PCD.

Background

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically defined process associated with distinctive morphological and biochemical characteristics, and is an integral part of the life cycle of multicellular organisms [1,2]。In plants, PCD occurs during developmental processes and in response to abiotic and biotic stresses [3,4]。金刚石信号通路主要涉及mitochondria and plasma membrane receptors, although it has recently been shown that ER stress caused by impaired ER function can also induce apoptotic pathways in animals and plants [5–7]。

The ER performs several important functions, including protein targeting and secretion, vesicle trafficking, and membrane biogenesis, and its proper function is essential to cell survival. Perturbations in ER homeostasis disrupt folding of proteins, leading to accumulation of unfolded proteins and protein aggregates. This condition is called ER stress and is detrimental to cell survival [5,8]。Under conditions of ER stress, a cell activates a signal transduction pathway termed the unfolded protein response (UPR) to limit the damage and maintain ER homeostasis [7,9,10]。Prolonged and excessive ER stress induces apoptosis, evidenced by DNA fragmentation, cytochromecrelease, and induction of caspase activity [11]。在哺乳动物中,ER应激凋亡帕特hway involves cross-talk between ER and mitochondria through Bcl-2 family members Bcl-2, Bax and Bak, which are localized in both mitochondria and ER [5]。Recent reports suggest that in animal cells, the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway mediated by Apaf-1 is an integral part of ER stress-induced apoptosis [2,5,11]。In plants, treatment with tunicamycin, an inhibitor of N-linked protein glycosylation, and cyclopiazonic acid, a blocker of plant ER-type IIA calcium pumps, elicits ER stress, followed by activation of PCD with typical apoptotic morphology [6,12]。However, the mechanisms of UPR and ER stress-induced PCD in plants remain largely unknown. One mechanism of ER stress response inArabidopsisinvolves membrane-associated bZIP transcription factors; following ER stress, bZIP28 and bZIP60 are processed and their released N-terminal domains are translocated to the nucleus to upregulate the expression of ER stress response genes including BiPs (ER chaperones), BI-1 (Bax-Inhibitor 1), PDI (protein disulfide isomerase), and calnexin [13–15]。

Genomic amplification (3 to 300 copies) of N-myc癌基因在人类神经母细胞瘤与ag)gressive tumor growth and poor prognosis [16]。Neuroblastoma Amplified Gene(NAG) was first identified as a gene co-amplified with the N-mycgene, althoughNAGis widely expressed in normal human tissues and its homologous sequences are found in plant databases [16,17]。Recently, it has been shown that NAG is localized in ER and is a component of the syntaxin 18 complex that is involved in Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport using human cell lines [18]。In this study, we investigatedin plantafunctions of NAG inNicotiana benthamiana. We showed thatN. benthamianaNAG (NbNAG) played a role in protein transport pathway, and NbNAG deficiency caused ER stress and cell death, suggesting its essential role in plant growth and survival.

Results

Identification of NbNAG

Functional genomics using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) revealed that silencing of theN. benthamianahomolog ofNeuroblastoma Amplified Gene(NAG), designatedNbNAG, results in growth arrest and acute plant death. The ~7.4 kb full-lengthNbNAGcDNA encodes a polypeptide of 2,409 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 270,589.33 Da (Additional file1: Figure S1). Database searches identified closely related genes in human, mouse, zebrafish,C. elegans,Arabidopsisand rice. TheNAGhomolog encodes a protein of ~2,400 amino acids inArabidopsis(At5g24350), rice (NP_001066451), and human (NP_056993), and is a single-copy gene in all three genomes. Our analyses showed that there is no null mutant ofNAGinArabidopsisT-DNA insertion lines. The NbNAG protein contains the Sec39 domain (residues 595–1126) that has been implicated in ER-Golgi trafficking in yeast [19]。Overall, NbNAG shows 49%, 42% and 29% sequence identity to the NAG homologs fromArabidopsis, rice, and human, respectively. NbNAG sequence was aligned with those of the NAG homologs fromArabidopsisand rice (Additional file1: Figure S1).

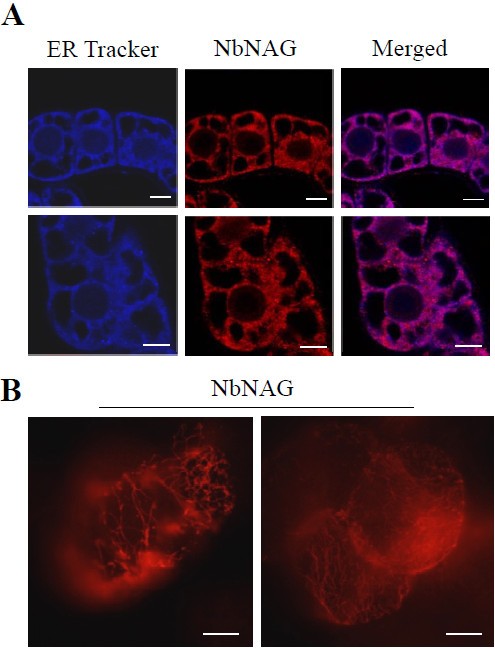

ER localization of NbNAG in tobacco BY-2 cells

To determine subcellular localization of NbNAG, we performed immunolabeling experiments in tobacco BY-2 cells using anti-NbNAG antibodies (Figure1).After immunolabeling with anti-NbNAG antibodies, BY-2 cells were briefly stained with ER Tracker™ Blue-White DPX as an ER marker. Confocal laser scanning microscopy revealed that red fluorescent signals of NbNAG overlapped with blue fluorescence of the ER Tracker near the nuclei and along the network in a typical ER localization pattern in BY-2 cells [20] (Figure1A). When the BY-2 cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy, they exhibited a network pattern of red fluorescence in the cytosol and in the nuclear periphery (Figure1B). These results suggest that NbNAG was mainly localized in the ER, consistent with the ER localization of the yeast and mammalian NAG [18,19]。

ER localization of NbNAG in tobacco BY-2 cells.A. BY-2 cells were immunolabeled with anti-NbNAG antibodies and briefly stained with ER. Tracker™ Blue-White DPX as an ER marker for observation with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Scale bars: 10 μm. B. After immunolabeling, the BY-2 cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescent and bright field images are shown. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Expression ofArabidopsis NAG

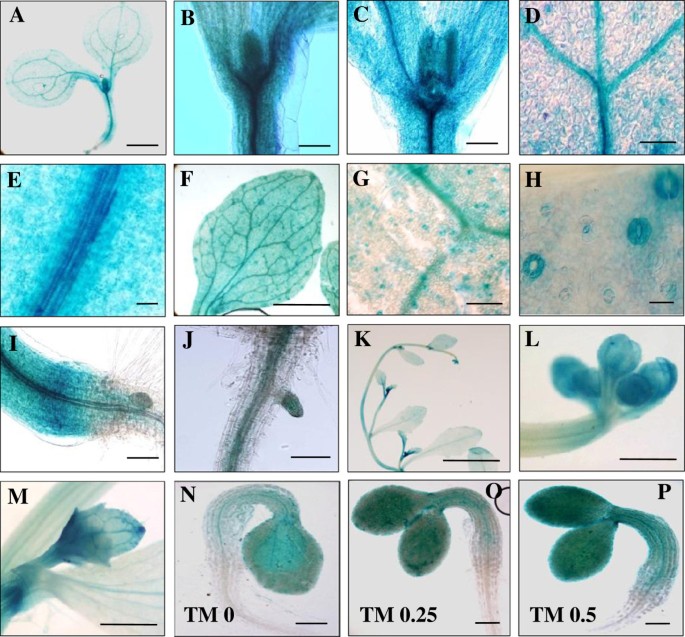

We transformedArabidopsiswith a fusion construct between theArabidopsis NAGpromoter (1,100 bp) andGUS(AtNAGp::GUS).The 1,100 bp promoter was the maximum size due to a closely located adjacent gene inArabidopsisgenome. GUS staining of seedlings demonstrated thatAtNAGpromoter activity was mainly detected in the aerial parts, particularly in shoot apical meristem, leaf primordia, developing vasculature, and stomata (Figure2A-I). In roots, GUS activity was localized in emerging lateral roots and root vasculature, albeit weakly (Figure2J). In the reproductive stage, flower buds and axillary buds showed GUS staining (Figure2K-M). In general,NAGexpression was concentrated in young aerial tissues containing dividing cells. Interestingly,AtNAGp::GUSactivity in a seedling increased in response to increasing concentrations of tunicamycin (TM), an inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation (Figure2N-P).

Histochemical localization ofAtNAGpromoter-GUSexpression inArabidopsis.InArabidopsistransgenic plants carrying theArabidopsis NAG(AtNAG) promoter-GUSfusion gene, GUS staining is shown in the following tissues: shoot of a seedling at 4 days after germination (DAG) (A); shoot apex and leaf primordia at 4 DAG (B) and 7 DAG (C); vascular bundles in the cotyledon (D) and the hypocotyl (E) at 4 DAG; vasculature (FandG) and stomata (FandH) of a true leaf at 7 DAG; hypocotyl-root junction at 4 DAG (I); root vasculature and emerging lateral root (J); flower buds and axillary buds in the reproductive stage (K), and enlarged pictures of the flower buds (L) and the axillary buds (M); a seedling at 2 DAG upon tunicamycin (TM) treatment at 0 (N), 0.25 (O), and 0.5 μg/ml (P).Scale bars:A= 2 mm,B,C,I, andL= 0.5 mm,D,G, andN-P= 200 μm,EandJ= 100 μm,FandM= 1 mm,H= 20 μm,K= 1 cm.

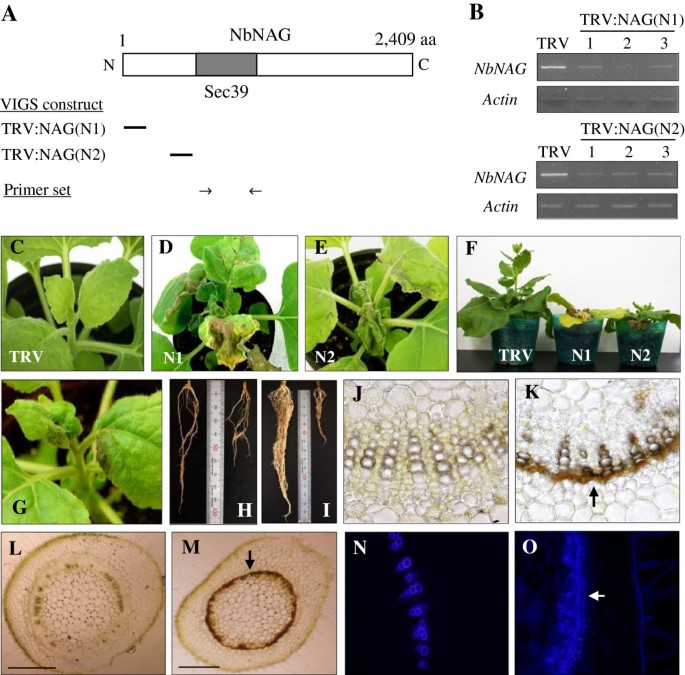

VIGS phenotypes and suppression of endogenousNbNAGtranscripts

For VIGS, we cloned two different fragments ofNbNAGcDNA into the TRV (Tobacco Rattle Virus)-based VIGS vector pTV00, and infiltratedN. benthamianaplants withAgrobacteriumcontaining each plasmid. TRV:NAG(N1) and TRV:NAG(N2) contain the non-overlapping 550 bp and 540 bp N-terminal regions of the cDNA, respectively (Figure3A). The effect of gene silencing on the level ofNbNAGmRNA was examined using semiquantitative RT-PCR (Figure3B)。减少大量的PCR产品生产n three independent plants from the TRV:NAG(N1) and TRV:NAG(N2) lines compared with TRV control, indicating that the endogenous level of theNbNAGtranscripts was reduced in those plants. The transcript levels of actin, which served as the control, remained constant.

VIGS constructs, phenotypes, and suppression of theNbNAGtranscripts. ASchematic drawing showing NbNAG structure and two VIGS constructs, TRV:NAG(N1) and TRV:NAG(N2), each containing a differentNbNAGcDNA fragment (indicated bybars).The primer set used for RT-PCR is also indicated.BSemiquantitative RT-PCR analysis ofNbNAGtranscript levels. Three independent VIGS plants were analyzed for TRV:NAG(N1) and TRV:NAG(N2) lines. The actin mRNA level was included as a control.C-FCell death phenotypes of TRV:NAG VIGS plants. Photographs of the plants were taken at 25 days after infiltration (DAI).GCell death phenotypes of TRV:NAG VIGS plants at 15 DAI.HandIRoot growth of TRV (left) and TRV:NAG lines (right) at 15 (H) and 25 DAI (I).J-MHand-cut sections of the petiole of the fourth leaf above the infiltrated leaf (JandK) and the stem where the fourth leaf above the infiltrated leaf was attached (LandM) from TRV (JandL) and TRV:NAG lines (KandM) at 15 DAI. Brown-colored dead cells in the vasculature are indicated by thearrows. Scale bars: 200 μm.NandOThe stem sections shown in (LandM) were observed under fluorescence microscopy to detect autofluorescent secondary metabolites in TRV (N) and TRV:NAG lines (O).Thearrowindicates the autofluorescence around the stem vasculature that undergoes cell death.

VIGS with TRV:NAG(N1) and TRV:NAG(N2) constructs resulted in growth arrest and acute plant death (Figure3C-F). Necrotic lesions were evident in young leaves around the shoot apex at 15–16 days after infiltration (DAI) (Figure3G). At 25 DAI, the shoot apex was completely abolished with no stem growth or new leaf formation (Figure3D, E). The lesions progressively expanded, leading to premature death of the plants. Root growth was also affected byNbNAGVIGS at 15 and 25 DAI (Figure3H, I). The petiole of the fourth leaf above the infiltrated leaf, and the stem where the fourth leaf above the infiltrated leaf was attached were cross-sectioned freehand and observed under light microscopy (Figure3J-M). The localized brown pigment in the petiole (Figure3K, cf. control in J) and the stem (Figure3M, cf. control in L) at 20 DAI indicates cell death in the vasculature of TRV:NAG lines, particularly in the cambium. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that TRV:NAG lines accumulated large amounts of autofluorescent secondary metabolites, which were also observed at infection sites during hypersensitive cell death [21], in the stem vasculature (Figure3O),和控制表现出荧光Only in the xylem tracheary elements (Figure3N).

Analysis of programmed cell death phenotypes

Although morphology and sizes of abaxial epidermal cells of the TRV:NAG leaves remained normal compared with TRV control (Figure4A), extension and fragmentation of nuclear chromatin was evident in TRV:NAG lines at 20 DAI (Figure4B), but not at 10 DAI when lesions were not formed yet (Additional file1: Figure S2A). DNA laddering was also observed in genomic DNA isolated from the TRV:NAG leaves (Figure4C). Since nuclear fragmentation and DNA laddering are hallmark features of PCD, these results suggest that silencing ofNbNAGactivates PCD in plants.

Phenotypes of programmed cell death. ARepresentative light micrographs of the abaxial leaf epidermis of TRV control and TRV:NAG lines (20 DAI). Scale bars: 100 μm.BNuclear degradation. Fluorescence micrographs of abaxial leaf epidermal cells from VIGS lines (20 DAI) after nuclear staining with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 100 μg/ml).COligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation. Genomic Southern blotting was performed using total genomic DNA ofN. benthamianaas a probe.D-FMitochondrial membrane integrity. Leaf protoplasts from VIGS lines (20 DAI) were observed after staining with TMRM (200 nM) (D).TMRM fluorescence (E) and chlorophyll autofluorescence (F) were quantified. Data points represent means ± SD of 20 individual protoplasts. Significant differences between control and other samples were indicated by one (P≤0.05) or two (P≤0.01)asterisks. PIV, pixel intensity values.GandHROS production. Leaf protoplasts were incubated with a ROS indicator H2DCFDA (2 μM) (G).荧光的原生质体中收取was quantified by pixel intensity (H).Data points represent means ± SD of 30 individual protoplasts. Scale bars: 50μm.

During apoptosis in animal cells, activation of the cell death pathway is initiated by modification of mitochondrial membrane permeability [3,4]。Mitochondrial membrane potential of leaf protoplasts from VIGS lines was monitored by TMRM (Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester) fluorescent probes that accumulate in mitochondria in proportion to the mitochondrial membrane potential [22]。的平均TMRM荧光和富:protop唠叨lasts was ~4-fold lower than that of TRV control at 20 DAI, indicating reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (Figures4D, E, Additional file1: Figure S5A), but there was no difference in TMRM fluorescence between TRV and TRV:NAG lines at 10 DAI (Additional file1: Figure S2B, C). Chlorophyll autofluorescence was not affected in TRV:NAG protoplasts at either 10 DAI (Additional file1: Figure S2B, D) or 20 DAI (Figures4D, F, Additional file1: Figure S5A). To test whether reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in the cell death phenotype of TRV:NAG plants, leaf protoplasts prepared from VIGS lines (20 DAI) were incubated with H2DCFDA that becomes activated in the presence of H2O2to produce green fluorescence. Accumulation of fluorescent H2DCFDA in TRV:NAG protoplasts was ~4.2-fold higher than in TRV control, indicating H2O2accumulation (Figures4G, H, Additional file1: Figure S5A).

Ultrastructural analyses of the cell death phenotype

Light (Additional file1: Figure S3A, B) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Additional file1: Figure S3C-L) of transverse leaf sections revealed degenerating spongy mesophyll cells at early and late stages in TRV:NAG lines, in contrast to TRV control cells at 25 DAI. TEM also showed disintegrating chloroplasts (Additional file1: Figure S3E, F, J) and mitochondria (Additional file1: Figure S3L), ruptured vacuoles (Additional file1: Figure S3E, F), and abnormal nuclei (Additional file1: Figure S3H) in TRV:NAG lines, compared with TRV control (Additional file1: Figure S3C, G, I, K). These results suggest that theNbNAG-induced cell death involves vacuole collapse leading to enzymatic degradation of organelles and cell contents, as demonstrated in PCD induced by other stimuli [23]。

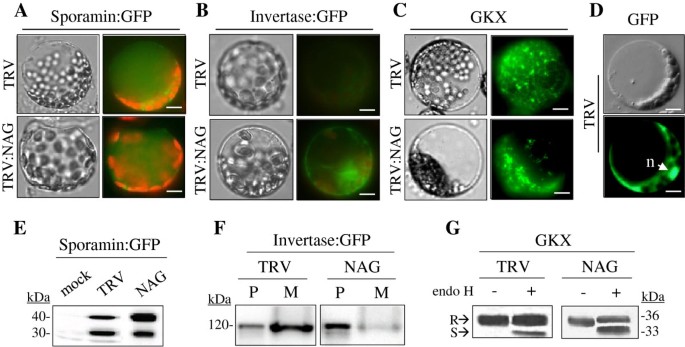

NbNAG deficiency inhibits intracellular protein transport

Yeast 82-kDa Sec39p (Dsl3p) is localized to the ER [24], and associated with the syntaxin 18 complex that is involved in Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport [19]。Human NAG containing a Sec39p-homologous region appears to be the ortholog of yeast Sec39p despite the marked difference in their molecular sizes, and plays a similar role in the Golgi-ER retrograde trafficking [18]。NbNAG also contains the Sec39 domain (amino acid residues 595–1126), indicating that NbNAG may be involved in protein trafficking in a plant cell. To test this possibility, protoplasts isolated from TRV and TRV:NAG leaves (10 DAI) were transformed withsporamin:GFP(Spo:GFP) construct encoding a fusion protein between green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the N-terminal region of sporamin as a vacuolar reporter gene (Figure5A). Previous experiments withArabidopsisprotoplasts showed that Spo:GFP is targeted to the central vacuole, where it is processed from a 40-kDa precursor to a 30-kDa form by proteolysis [25]。Consistent with the results, fluorescence microscopy revealed Spo:GFP in the central vacuole in both TRV and TRV:NAG protoplasts (Figure5A), while GFP alone was localized in the cytosol and the nucleus in TRV protoplasts (Figure5D). To measure trafficking efficiency, relative amounts of the precursor and the processed form of Spo:GFP were compared in transformed TRV and TRV:NAG protoplasts by immunoblotting using anti-GFP antibody (Figures5E, Additional file1: Figure S5B). In TRV protoplasts, ~44% of Spo:GFP was in the 40 kDa precursor form; however, in TRV:NAG protoplasts, the precursor form is visibly dominant, indicating that NbNAG deficiency leads to reduced vacuole trafficking of Spo:GFP.

Inhibition of intracellular trafficking of diverse cargo proteins. AVacuolar localization of sporamin:GFP, a fusion protein between sporamin and green fluorescent protein (GFP). Protoplasts isolated from TRV and TRV:NAG leaves were transformed with the sporamin:GFP construct. Fluorescent and bright field images are shown. Red fluorescence indicates chlorophyll autofluorescence. Scale bars: 10 μm.BLocalization of invertase:GFP. Because invertase:GFP is a secretory protein, its fluorescence was not readily detected within protoplasts of TRV control . Scale bars: 10 μm.CLocalization of GKX. GKX is a chimeric ER membrane marker [27]。Scale bars: 10 μm.DLocalization of GFP control in the cytosol and the nucleus of TRV protoplasts. Scale bars:10 μm.ETrafficking assay of sporamin:GFP. Protein extracts prepared from protoplasts transformed with the sporamin:GFP construct were analyzed by western blotting using anti-GFP antibody. Mock indicates untransformed TRV protoplasts.FTrafficking assay of invertase:GFP. Protein extracts prepared from protoplasts (P) and medium (M) were analyzed by western blotting using anti-GFP antibody.GEndo H resistance of GKX glycans. Protein extracts from protoplasts transformed with the GKX construct were treated with endo H and analyzed by western blotting using anti-GFP antibody.SandRindicate endo H-sensitive GKX proteins (ER form) and endo H-resistant proteins (Golgi form), respectively.

We next examined the effects of NbNAG depletion on the secretory pathway using invertase:GFP, a chimeric protein consisting of full-length secretory invertase and GFP [26], as a reporter (Figure5B). After transformation with the invertase:GFP construct, green fluorescent signals were not detectable in TRV protoplasts, indicating that invertase:GFP was secreted into the medium as previously observed [26]。However, invertase:GFP signal was readily detected in TRV:NAG protoplasts (Figure5B)。为了证实这一发现,蛋白质提取ed from the protoplasts and the incubation medium, and analyzed by western blot analysis with anti-GFP antibody (Figures5F, Additional file1: Figure S5B). In TRV controls, invertase:GFP (~120 kDa) was mainly detected in the medium, while a minor portion of the protein remained in the protoplasts. In contrast, in the TRV:NAG line the fusion protein was predominantly present in the protoplasts, suggesting that NbNAG depletion blocked the secretion of invertase:GFP into the medium.

Next, we examined ER-Golgi transport using an artificial ER marker protein, GKX [27]。TRV protoplasts transformed withGKXexhibited a reticular network pattern of green fluorescence (Figure5C) as observed previously [27]。However, TRV:NAG protoplasts expressing GKX displayed a punctate and aggregated fluorescence signal, suggesting disruption of the ER network. Since GKX contains an N-glycosylation site, we examined the sensitivity of the N-glycans of GKX to endoglycosidase H (endo H) treatment. It has been reported that the N-glycans of ER proteins are sensitive to endo H, while the N-glycans of Golgi proteins are resistant due to modification [28,29]。Protein extracts from TRV and TRV:NAG protoplasts were digested by endo H prior to western blotting with anti-GFP antibody (Figure5G). In the TRV control, endo H digestion of GKX resulted in two bands, ~33 kDa endo H-sensitive GKX proteins (ER form) and ~36 kDa endo H-resistant proteins (Golgi form). These results indicate that a large part of GKX proteins was transported from ER to Golgi complex through anterograde trafficking. TRV:NAG lines also contained both the ER and the Golgi forms, but the ratio of the ER form to the Golgi form was higher than in TRV controls (Figures5G, Additional file1: Figure S5B). These results provide evidence that protein transport from ER to Golgi complex was inhibited by NbNAG deficiency.

NbNAG-silencing causes ER stress

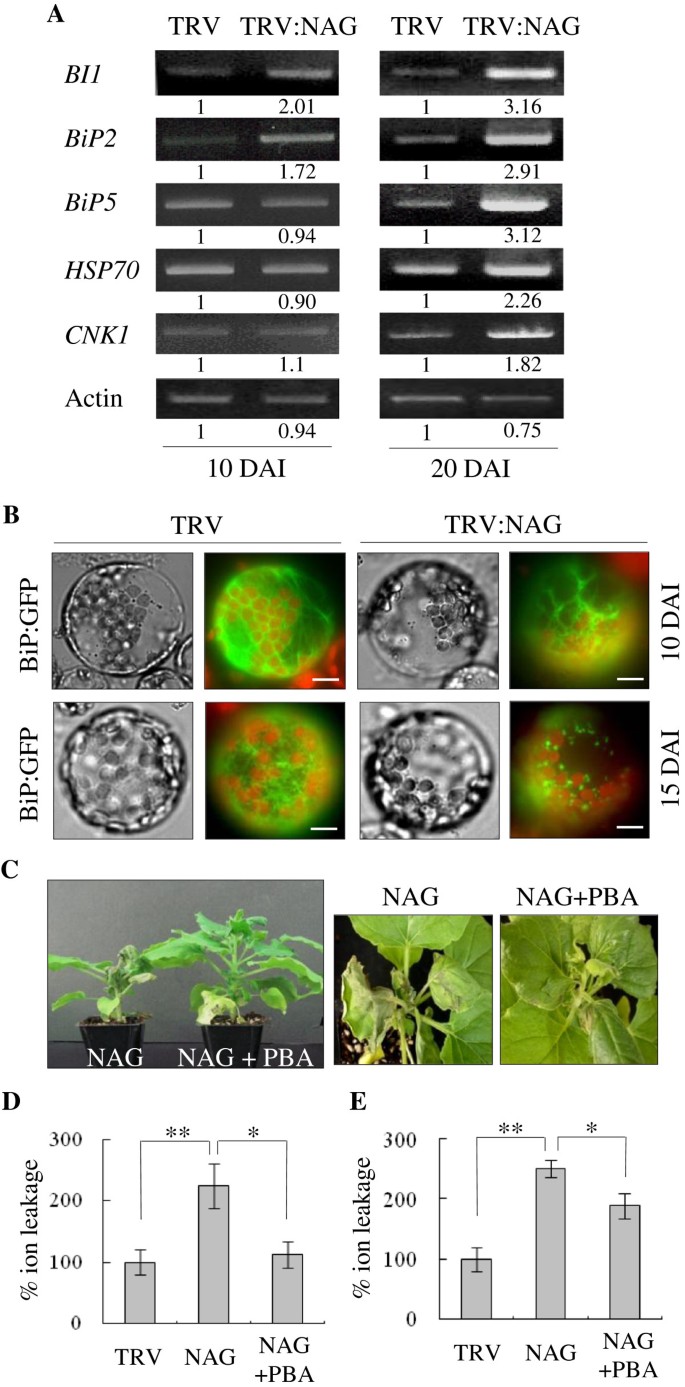

The abnormal ER morphology shown by GKX expression raised a possibility that NbNAG-deficient plants may have been subjected to ER stress. Transcriptome analysis in response to tunicamycin-induced ER stress inArabidopsisrevealed transcriptional up-regulation of the genes encoding BiPs, BI1 (Bax-Inhibitor 1), CNK1, and HSP70 [6,10]; therefore, we examined transcript levels of these ER stress-related genes in TRV and TRV:NAG lines. Semiquantitative RT-PCR revealed increased transcript levels ofBI1andBiP2in TRV:NAG lines compared with TRV control at 10 DAI, whileBI1,BiP2,BiP5,CNK1, andHSP70genes were all induced at 20 DAI (Figure6A).

ER stress phenotypes. ASemiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of transcript levels of ER stress-related genes in TRV and TRV:NAG leaves at 10 and 20 DAI. Relative band intensity was shown below the bands.BAltered ER morphology. As an ER marker, BiP:GFP construct was transformed into leaf protoplasts of TRV and TRV:NAG lines at 10 and 15 DAI. BiP is a HSP70 chaperone located in the ER lumen. Red fluorescence indicates chlorophyll autofluorescence. Scale bars: 10 μm.CEffect of the chemical chaperone 4-phenyl butyric acid (PBA) on growth retardation and cell death phenotypes in TRV:NAG VIGS lines at 25 DAI. Representative plants are shown.DandERelative ion leakage (%) of the 4th leaf above the infiltrated leaf (D) and the leaf near the shoot apex (E).Each value represents the mean ± SD of three replicates per experiment.

To further observe ER morphology, we transiently expressed a chimeric lumenal protein, BiP:GFP, a fusion protein between BiP (lumenal binding protein) and GFP, in protoplasts from TRV and TRV:NAG lines (Figure6B). At 10 DAI, the fluorescent signal of BiP:GFP was localized in a reticular membranous network throughout the cytoplasm of both TRV control and TRV:NAG lines. At 15 DAI, the signal was punctate and fragmented in TRV:NAG lines indicating a disrupted ER network, while TRV exhibited normal ER morphology (Figure6B).

We next tested whether the chemical chaperone 4-phenyl butyric acid (PBA) alleviatesNbNAG-induced cell death (Figure6C-E). PBA relieves ER stress by directly reducing the load of misfolded proteins retained in the ER and has been shown to mitigate ER stress-induced cell death in mammals and plants [6,30,31]。Treatment with PBA (1 mM) partially rescued the growth retardation and cell death phenotypes of TRV:NAG lines (Figure6C). Elevated ion leakage, an indicator of cellular membrane leakage, in TRV:NAG lines was also alleviated by PBA treatment in the 4th leaf above the infiltrated leaf (Figures6D, Additional file1: Figure S5A) and in the leaf near the shoot apex (Figures6E, Additional file1: Figure S5A). These results suggest that the defects in protein transport may cause ER stress in NbNAG-deficient cells.

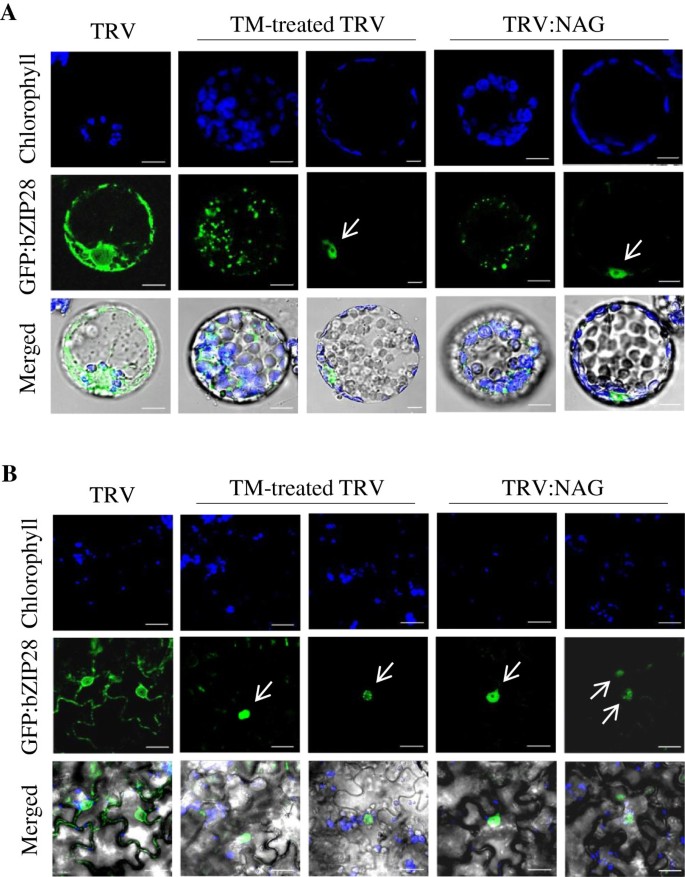

Nuclear translocation of bZIP28

InArabidopsis, tunicamycin-induced ER stress causes proteolytic processing and nuclear relocation of an ER membrane-associated transcription factor, bZIP28 [14,15]。We therefore tested whether silencing ofNbNAGsimilarly induced nuclear relocation of bZIP28 from the ER membrane (Figure7).AGFP:bZIP28construct in whichGFPwas fused toArabidopsis bZIP28was transiently expressed in TRV and TRV:NAG leaves (15 DAI) by agro-infiltration. Protoplasts prepared from the infiltrated leaves were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Figure7A) and fluorescence microscopy (Additional file1: Figure S4) to observe GFP:bZIP28 fluorescence in the mesophyll cells. In addition, infiltrated leaves were directly examined to observe the fluorescence in the epidermal cells (Figure7B). Protoplasts and leaf epidermal cells from TRV control exhibited a network pattern of green fluorescence in the cytosol and in the nuclear periphery as previously observed [14]。However, protoplasts from TRV:NAG lines and tunicamycin (TM)-treated TRV lines (the positive control) frequently showed a punctuate and aggregated GFP signal in the cytosol, revealing an abnormal ER network (Figures7A, Additional file1: Figure S4). Furthermore, some of the protoplasts and the epidermal cells exhibited strong GFP fluorescence in the nucleus with little fluorescence remaining in the cytoplasm (Figures7A, B, Additional file1: Figure S4). Since nuclear relocation of GFP:bZIP28 was not observed in TRV protoplasts or TRV epidermal cells, these results suggest that NbNAG deficiency activates the ER stress response.

Subcellular localization of GFP:bZIP28. ATRV control, tunicamycin (TM)-treated TRV, and TRV:NAG plants (15 DAI) were infiltrated withAgrobacteriumcontaining GFP:bZIP28 construct. After 24 h, protoplasts were isolated and localization of GFP fluorescent signals was examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Representative images of the protoplasts are shown. Scale bars: 10 μm.BAfter agroinfiltration of the GFP:bZIP28 construct, leaf epidermal cells were observed by confocal microscopy. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Discussion

Neuroblastoma-Amplified Gene(NAG) encodes a large protein (~2,400 amino acids) containing the Sec39 domain in plants and mammals. In human neuroblastoma,NAGwas found to be co-amplified with N-myconcogene, of which genomic amplification correlates with aggressive tumor growth [16]。Despite the marked size difference, the NAG ortholog of yeast appears to be Sec39p (Dsl3p), a cytosolic protein of ~82 kDa, that is peripherally associated with the ER membrane [19]。Sec39p was first identified as an essential protein involved in ER-Golgi transport in a large-scale promoter shutoff analysis of essential yeast genes [32]。Further characterization revealed that Sec39p is a component of the Dsl1p complex that also includes Dsl1p, Tip20p, and ER-localized Q-SNARE proteins [19,33]。The Dsl1p complex is essential for retrograde traffic from the Golgi to ER, and consistently,Sec39showed strong genetic interaction with other factors required for Golgi-ER retrograde transport [19,34]。Interestingly, the temperature-sensitivesec39mutants also exhibited defects in forward transport between the ER and Golgi [19], consistent with the results by Mnaimneh et al. [32]。The phenotype can be explained by the fact that retrograde traffic plays an important role in recycling ER-resident proteins that have escaped from the ER [35,36]。Thus, a blocked retrograde pathway can result in failure to retrieve these proteins and lead to a concomitant block in anterograde transport.

Mammals possess functional orthologs of the components of the yeast Dsl1p complex, despite a low degree of sequence conservation between the yeast and mammalian counterparts [37]。Recently, it has been revealed that mammalian NAG is a subunit of the Syntaxin 18 complex involved in Golgi-to-ER retrograde trafficking and serves as a link between p31 and ZW10-RINT-1 in the mammalian ER fusion machinery [18]。Interestingly, silencing ofNAGin human cell lines using RNA interference did not substantially disrupt Golgi morphology or the ER-to-Golgi anterograde trafficking, but caused defects in protein glycosylation [18]。In this study, we characterizedin vivoeffects of NAG deficiency in plants.NAGfromN. benthamiana,Arabidopsis, and rice all encodes a ~2,400 kDa protein with the Sec39 domain that is mainly localized in ER, similar to the mammalian NAG. Knockdown ofNbNAGusing VIGS led to reduced protein transport between ER and Golgi, and a concomitant decrease in trafficking of the marker proteins to vacuole and to plasma membrane for secretion. Furthermore, NAG depletionin plantacaused ER stress and PCD.

Our data suggest that ER stress caused by disrupted protein transport contributes to PCD activation inNbNAG-silenced plants. First, expression of the UPR-related genes such asBiP2,BiP5, BI1(Bax inhibitor-1),HSP70, andCNK1was up-regulated inNbNAG-silenced VIGS plants.BiPsencode ER-localized chaperones and have been used as marker genes for UPR activation in plants [12,38], and similarly, expression ofBI1,HSP70, andCNK1was induced during tunicamycin-induced ER stress inArabidopsis[6]。Second, NbNAG deficiency caused proteolytic processing and nuclear relocation of bZIP28 transcription factor, which is normally associated with the ER membrane. It has been shown that bZIP28 processing is activated by ER stress-inducing agents such as tunicamycin and dithiothreitol, but not by salt stress [14]。Third, the chemical chaperone PBA alleviated the growth retardation and cell death phenotypes ofNbNAGVIGS plants. PBA suppresses ER stress and ER-mediated apoptosis by chemically enhancing the capacity of the ER to remove misfolded proteins in mammals and plants [6,30,31]。In addition, expression analyses of theArabidopsis NAGpromoter-GUSfusion gene showed thatAtNAG启动子活性刺激来回应你nicamycin. Thus NbNAG appears to play a crucial role in protein transport during plant growth and development, and its deficiency causes ER stress response and subsequent activation of PCD. NbNAG-mediated cell death was first observed in young tissues containing actively dividing cells such as the shoot apex and vascular cambium before expanding to other tissues (Figure3), consistent with the fact that young tissues have elevated demands for protein synthesis and transport.

Interestingly, mutations that inhibit the ER to Golgi trafficking have not always caused ER stress and PCD as observed inNbNAGVIGS plants. For example, a missense mutation in the COPII coat protein Sec24A caused the formation of aberrant tubular clusters of ER and Golgi membrane inArabidopsiswithout inducing PCD [39]。In yeast and mammals, the COPII coat forms transport vesicles on the ER surface for the ER-Golgi anterograde trafficking, and the COPII coat protein Sec24A is believed to have a specific role in cargo selection via site-specific recognition of cargo signals [39]。In another case, overexpression of AtPRA1.B6, a prenylated Rab acceptor 1, resulted in inhibition of COPII vesicle-mediated anterograde trafficking but did not induce either ER stress or PCD [40]。The lack of PCD activation in the Sec24A mutant may be linked to the fact that the missense mutation caused only a partial loss of Sec24A function, affecting the anterograde trafficking of only a subset of cargos [39]。Total loss of Sec24A function instead led to an embryonic lethality, suggesting that the gene function is essential inArabidopsis[39]。Similarly, because AtPRA1.B6 functions as a negative regulator of the anterograde transport of only a subset of proteins at the ER, the effect of its overexpression appeared to be rather specific and limited [40]。In this study, the severe consequences of NbNAG depletion suggest that NbNAG function in the protein transport pathway may be essential and/or common so that its deficiency severely disturbs the system. Alternatively, NbNAG may have additional, yet unidentified, functions, of which disruption induces PCD in a plant cell.

Although the underlying mechanism remains unclear, recent evidence indicates that mitochondria-dependent and –independent cell death pathways both play a role in ER stress-induced apoptosis [5,8,41]。Well-known regulators of mammalian apoptosis, such as the Bcl-2 family and caspases, are activated during ER stress [5,41]。bcl - 2、Bax和贝克驻留在ER膜well as in the mitochondrial outer membrane, regulating homeostasis and apoptosis in the ER [5]。Overexpression of Bcl-2 or deficiency of the proapoptotic proteins Bax and Bak confers protection against ER stress-induced apoptosis, indicating that Bcl-2 family members participate in the integration of apoptotic signals between the ER and mitochondria [42,43]。In this study, NbNAG-induced cell death showed apoptotic hallmarks, such as nuclear DNA fragmentation, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, and excessive production of reactive oxygen species. These apoptotic features are similar to the phenotypes of ER stress-induced PCD inArabidopsis根和大豆tunicamy引起的细胞培养cin and cyclopiazonic acid, respectively [6,44]。In particular, the decreased mitochondrial membrane potential strongly indicates involvement of mitochondria in NbNAG-induced PCD, at least at the stage we examined. It will be important to determine whether several pro-apoptotic pathways simultaneously function to commit the cell to death during ER stress, and how the different signals from the ER are integrated to activate PCD in plants.

Conclusion

Nicotiana benthamania Neuroblastoma-Amplified Gene(NbNAG) encodes an ER-localized protein of 2,409 amino acids that contains the secretory pathway Sec39 domain. NbNAG plays a role in protein transport pathway, and NbNAG deficiency resulted in ER stress and programmed cell death, presumably caused by a blocked secretion pathway. These results suggest that NAG, a conserved protein from yeast to mammals, plays an essential role in plant growth and development.

Methods

Virus-induced gene silencing

Virus-induced gene silencing was performed as described [22,45,46]。NbNAGcDNA fragments were PCR-amplified and cloned into the pTV00 vector containing part of the tobacco rattle virus (TRV) genome using the following NbNAG specific primers: NbNAG N1 (5'-aagcttatggaggaatcaact-3' and 5'-gggcccttggatcttgattga-3') and NbNAG N2 (5'-aagcttgttacagaatggaat-3' and 5'-gggcccagatatgccaagtcc-3'). The recombinant pTV00 plasmids and the pBINTRA6 vector containing RNA1 required for virus replication were separately transformed intoAgrobacterium tumefaciensGV3101 strain. After grown to saturation, theAgrobacteriumculture was centrifuged and resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES and 150 μM acetosyringone, and kept at room temperature for 2 h. Separate cultures containing pTV00 and pBINTRA6 were mixed in a 1:1 ratio. The third leaf ofN. benthamiana(3-week old) was pressure-infiltrated with the mixedAgrobacteriumsuspension as described [47]。Since theAgrobacteriuminfiltration intoN. benthamianaleaves causes systemic spread of gene silencing signal into upper leaves and vasculature of the growing plants, the gene silencing phenotypes were observed in the newly emerged tissues at approximately 2 weeks after infiltration. The 4th leaf above the infiltrated leaf was used for semiquantitative RT-PCR.

Cloning ofNbNAG

The partialNbNAGcDNA used in the VIGS screening was ~1.8 kb in length and corresponded to the N-terminal end of the predicted protein. We searchedN. benthamianaandN. tabacumEST databases usingArabidopsisand riceNAGsequences to find aN. tabacumclone (BP130717) containing the C-terminal end of theNAGgene. Using a long range PCR amplification kit (Qiagen), we amplified a ~7.4 kb cDNA fragment using cDNA synthesized fromN. benthamianaseedling RNA as template and primers corresponding to the 5’-termimal sequence of the ~1.8 kb cDNA (5'-caccctcaaggagagatggagaaagcag-3') and the 3’-terminal sequence of the tobacco clone (5'-agcttctgctcgacagtatccaag-3'). The amplified fragment was cloned into TOPO cloning vector (TOPORXL PCR cloning kit) and sequenced.

GUS histochemical assay

TheAtNAGpromoter sequence was PCR-amplified fromArabidopsisgenomic DNA using primers 5'-aagcttgtggaatattattttcaa-3' and 5'-ggatccgatcaatcgagatcgatc-3'. The 1,100 bp promoter was cloned into pBI101 vector using HindIII/BamHI sites to generate theAtNAGpromoter-GUSfusion gene. The recombinant Ti-plasmid was introduced intoA. tumefaciensLBA4404 forArabidopsistransformation. GUS staining of the transgenicArabidopsislines was performed as described [48]。

RNA isolation and semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed with RNA isolated from the fourth leaf above the infiltrated leaf as described [45], with 15–35 cycles of amplification. The endogenousNbNAGtranscript was detected using the primers 5'-ctgggagttcacctcctcca-3' and 5'-gcgagctcaacccaagaagt-3'. To detectBiPandHSP70transcripts, the following primers were designed based on the publishedN. benthamianaand tobacco cDNA sequences:BI1(5'-gcaatcgctggagttacgat-3' and 5'-ccaaggtgtgc cttctcaat-3'),BiP2(X60059; 5'-agtgcaacagctcctgaagga-3' and ctgttacgggcatcaatcctc-3'),BiP5(X60058; 5'-tggaagagacgcgcatccttg-3' and 5'-gaccaggatgttcttttcacc-3'),HSP70(NP1072062; 5'-cactctcatccactgctcaga-3' and 5'-gtggtcttgtcctcagcagag-3'), and actin (5'-tggactctggtgatggtgtc-3' and 5'-cctccaatccaaacactgta-3').

Histochemical analyses

Tissue sectioning, light microscopy, and transmission electron microscopy were carried out using the fourth or fifth leaf above the infiltrated leaf of the VIGS lines as described [22]。

Measurement ofin vivoH2O2, mitochondrial membrane potential, and DNA fragmentation analysis

These experiments were carried out as described [22]。

Immunolabeling

Anti-NbNAG antibodies were generated in rabbits against an N-terminal region (351 amino acids) of NbNAG using antibody production services of AbFrontier (http://www.abfrontier.com).2细胞和immunofluorescenc做准备e were performed as described [49,50]。Fixed and permeabilized BY-2 cells were immunolabeled with 1:500 dilution of anti-NbNAG antibodies. Then the cells were incubated with 1:1000 dilution of Alexa Fluor® 594-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Molecular Probes). To mark the ER, the cells were briefly stained with 1 μM ER Tracker™ Blue-White DPX (Molecular Probes). Then the BY-2 cells were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss LSM 510) with optical filters LP 560 (excitation 543 nm, emission 560–615 nm) and BP420-480 (excitation 405 nm, emission 461 nm) for Alexa Fluor 594 and ER Tracker, respectively. The BY-2 cells were also observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71).

Transient expression of reporter proteins

Cloning of Sporamin:GFP, Invertase:GFP, GKX, and BiP:GFP was previously described [25,26,40,51]。Plasmids (15 μg) were introduced into protoplasts prepared from the fourth leaf above the infiltrated leaf of VIGS lines at 10 days after infiltration (DAI) by polyethylene glycol mediated transformation. Expression of the fusion constructs was monitored at various time points after transformation, and images were captured with a cooled CCD camera and a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescence microscope (Jena, Germany) according to [52]。

Protein preparation and western blot analysis

To prepare cell extracts from protoplasts, transformed protoplasts were subjected to repeated freeze and thaw cycles in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml antipain, 2 mg/ml aprotinins, 0.1 mg/ml E-64, 0.1 mg/ml leupeptin, 10 mg/ml pepstatin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and then centrifuged at 7,000gat 4°C for 5 min [51]。To extract proteins from culture medium, cold TCA (100 μl) was added to the medium (1 ml), and protein aggregates were precipitated by centrifugation at 10,000gat 4°C for 5 min. The protein aggregates were dissolved in the same volume of lysis buffer used to prepare total protoplast proteins. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-GFP antibody (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) as described previously [51]。

Endo H treatment

Endo H treatment was performed according to [52]。Protein extracts were prepared from transformed protoplasts and denatured in denaturation solution (1% SDS, 2% β-mercaptoethanol) by 10 min incubation at 100°C. Denatured proteins were incubated with 2 mg/ml endo H (Roche Diagnostics) in G5 buffer (50 mM sodium citrate, pH 5.5) at 37°C for 2 h. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting with anti-GFP antibody (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA).

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression

Agro-infiltration was carried out as described [53]。Protoplasts were prepared from the infiltrated leaves of TRV and TRV:NAG plants (15 DAI) 24 h post-infiltration, and GFP:bZIP28 fluorescence was observed by fluorescence microscopy.

Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) treatment and ion leakage measurement

Each experiment was performed three times using 10 plants per treatment. Starting at 5 DAI, TRV:NAG plants were irrigated every other day with 1 mM PBA or distilled water until 25 DAI. Leaf discs were prepared from multiple independent TRV:NAG plants for analysis. Sample preparation and conductivity measurements were carried out as described [45]。

Measurement of band intensity

The band intensity in the RT-PCR and immunoblotting analyses was measured using the AnalySIS LS Research program (Olympus).

Statistical analyses

Two-tailed Student’st-tests were performed using the Minitab 16 program (Minitab Inc.;http://www.minitab.com/en-KR/default.aspx) to investigate the statistical differences between the responses of the samples. Significant differences between control and other samples were indicated by one (P≤ 0.05) or two (P≤0.01) asterisks.

Accession number

Genbank accession number: EU602317 (NbNAG)

References

Vaux DL, Korsmeyer SJ: Cell death in development. Cell. 1999, 96: 245-254. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80564-4.

Wertz IE, Hanley MR: Diverse molecular provocation of programmed cell death. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996, 21: 359-364.

Lam E, Kato N, Lawton M: Programmed cell death, mitochondria and the plant hypersensitive response. Nature. 2001, 411: 848-853. 10.1038/35081184.

Reape TJ, McCabe PF: Apoptotic-like programmed cell death in plants. New Phytol. 2008, 180: 13-26. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02549.x.

Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A: Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7: 880-885. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779.

Watanabe N, Lam E: BAX inhibitor-1 modulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated programmed cell death inArabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2007, 283: 3200-3210. 10.1074/jbc.M706659200.

Urade R: The endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling pathways in plants. Biofactors. 2009, 35: 326-331. 10.1002/biof.45.

Boyce M, Yuan J: Cellular response to endoplasmic reticulum stress: a matter of life or death. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13: 363-373. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401817.

Kaufman RJ, Scheuner D, Schröder M, Shen X, Lee K, Liu CY, Arnold SM: The unfolded protein response in nutrient sensing and differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002, 3: 411-421. 10.1038/nrm829.

Urade R: Cellular response to unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum of plants. FEBS J. 2007, 274: 1152-1171. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05664.x.

Shiraishi H, Okamoto H, Yoshimura A, Yoshida H: ER stress-induced apoptosis and caspase-12 activation occurs downstream of mitochondrial apoptosis involving Apaf-1. J Cell Sci. 2006, 119: 3958-3966. 10.1242/jcs.03160.

Zuppini A, Navazio L, Mariani P: Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced programmed cell death in soybean cells. J Cell Sci. 2004, 117: 2591-2598. 10.1242/jcs.01126.

Iwata Y, Koizumi N: AnArabidopsistranscription factor, AtbZIP60, regulates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in a manner unique to plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102: 5280-5285. 10.1073/pnas.0408941102.

Liu J-X, Srivastava R, Che P, Howell SH: An endoplasmic reticulum stress response inArabidopsisis mediated by proteolytic processing and nuclear relocation of a membrane-associated transcription factor, bZIP28. Plant Cell. 2007, 19: 4111-4119. 10.1105/tpc.106.050021.

Liu J-X, Howell SH: bZIP28 and NF-Y transcription factors are activated by ER stress and assemble into a transcriptional complex to regulate stress response genes inArabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010, 22: 782-796. 10.1105/tpc.109.072173.

Wimmer K, Zhu XX, Lamb BJ, Kuick R, Ambros PF, Kovar H, Thoraval D, Motyka S, Alberts JR, Hanash SM: Co-amplification of a novel gene,NAG, with theN-mycgene in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 1999, 18: 233-238. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202287.

Scott D, Elsden J, Pearson A, Lunec J: Genes co-amplified withMYCNin neuroblastoma: silent passengers or co-determinants of phenotype?. Cancer Lett. 2003, 197: 81-86. 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00086-7.

Aoki T, Ichimura S, Itoh A, Kuramoto M, Shinkawa T, Isobe T, Tagaya M: Identification of the Neuroblastoma-amplified gene product as a component of the syntaxin 18 complex implicated in Golgi-to-endoplasmic reticulum retrograde transport. Mol Biol Cell. 2009, 20: 2639-2649. 10.1091/mbc.E08-11-1104.

Kraynack BA, Chan A, Rosenthal E, Essid M, Umansky B, Waters MG, Schmitt HD: Dsl1p, Tip20p, and the novel Dsl3(Sec39) protein are required for the stability of the Q/t-SNARE complex at the endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2005, 16: 3963-3977. 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0056.

Takeuchi M, Ueda T, Sato K, Abe H, Nagata T, Nakano A: A dominant negative mutant of sar1 GTPase inhibits protein transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus in tobacco andArabidopsiscultured cells. Plant J. 2000, 23: 517-525. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00823.x.

Kombrink E, Schmelzer E: The hypersensitive response and its role in local and systemic disease resistance. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2001, 107: 69-78. 10.1023/A:1008736629717.

Kim M, Kim JH, Ahn SH, Park K, Kim GT, Kim WT, Pai H-S: Mitochondria-associated hexokinases play a role in the control of programmed cell death inNicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell. 2006, 18: 2341-2355. 10.1105/tpc.106.041509.

Obara K, Kuriyama H, Fukuda H: Direct evidence of active and rapid nuclear degradation triggered by vacuole rupture during programmed cell death inZinnia. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125: 615-626. 10.1104/pp.125.2.615.

Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O'Shea EK: Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003, 425: 686-691. 10.1038/nature02026.

Sohn EJ, Kim ES, Zhao M, Kim SJ, Kim H, Kim YW, Lee YJ, Hillmer S, Sohn U, Jiang L, Hwang I: Rha1, anArabidopsisRab5 homolog, plays a critical role in the vacuolar trafficking of soluble cargo proteins. Plant Cell. 2003, 15: 1057-1070. 10.1105/tpc.009779.

Kim H, Park M, Kim SJ, Hwang I: Actin filaments play a critical role in vacuolar trafficking at the Golgi complex in plant cells. Plant Cell. 2005, 17: 888-902. 10.1105/tpc.104.028829.

Lee MH, Jung C, Lee J, Kim SY, Lee Y, Hwang I: AnArabidopsisprenylated Rab acceptor 1 isoform, AtPRA1.B6, displays differential inhibitory effects on anterograde trafficking of proteins at the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157: 645-658. 10.1104/pp.111.180810.

Rabouille C, Hui N, Hunte F, Kieckbusch R, Berger EG, Warren G, Nilsson T: Mapping the distribution of Golgi enzymes involved in the construction of complex oligosaccharides. J Cell Sci. 1995, 108: 1617-1627.

Crofts AJ, Leborgne-Castel N, Hillmer S, Robinson DG, Phillipson B, Carlsson LE, Ashford DA, Denecke J: Saturation of the endoplasmic reticulum retention machinery reveals anterograde bulk flow. Plant Cell. 1999, 11: 2233-2248.

Qi X, Hosoi T, Okuma Y, Kaneko M, Nomura Y: Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate protects against cerebral ischemic injury. Mol Pharmacol. 2004, 66: 899-908. 10.1124/mol.104.001339.

de Almeida SF, Picarote G, Fleming JV, Carmo-Fonseca M, Azevedo JE, de Sousa M: Chemical chaperones reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress and prevent mutant HFE aggregate formation. J Biol Chem. 2007, 282: 27905-27912. 10.1074/jbc.M702672200.

Davierwala美联社Mnaimneh年代,海恩斯J•莫法特J,钢笔g WT, Zhang W, Yang X, Pootoolal J, Chua G, Lopez A: Exploration of essential gene functions via titratable promoter alleles. Cell. 2004, 118: 31-44. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.013.

Gavin AC, Aloy P, Grandi P, Krause R, Boesche M, Marzioch M, Rau C, Jensen LJ, Bastuck S, Dümpelfeld B: Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature. 2006, 440: 631-636. 10.1038/nature04532.

Ungar D, Hughson FM: SNARE protein structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003, 19: 493-517. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.155609.

Reilly BA, Kraynack BA, VanRheenen SM, Waters MG: Golgi-to-endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retrograde traffic in yeast requires Dsl1p, a component of the ER target site that interacts with a COPI coat subunit. Mol Biol Cell. 2001, 12: 3783-3796.

Lee MCS, Miller EA, Goldberg J, Orci L, Schekman R: Bi-directional protein transport between the ER and Golgi. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004, 20: 87-123. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.105307.

Hirose H, Arasaki K, Dohmae N, Takio K, Hatsuzawa K, Nagahama M, Tani K, Yamamoto A, Tohyama M, Tagaya M: Implication of ZW10 in membrane trafficking between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. EMBO J. 2004, 23: 1267-1278. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600135.

Martínez IM, Chrispeels MJ: Genomic analysis of the unfolded protein response inArabidopsisshows its connection to important cellular processes. Plant Cell. 2003, 15: 561-576. 10.1105/tpc.007609.

Faso C, Chen YN, Tamura K, Held M, Zemelis S, Marti L, Saravanan R, Hummel E, Kung L, Miller E, Hawes C, Brandizzi F: A missense mutation in theArabidopsisCOPII coat protein Sec24A induces the formation of clusters of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Plant Cell. 2009, 21: 3655-3671. 10.1105/tpc.109.068262.

Lee MH, Jung C, Lee J, Kim SY, Lee Y, Hwang I: An Arabidopsis prenylated Rab acceptor 1 isoform, AtPRA1.B6, displays differential inhibitory effects on anterograde trafficking of proteins at the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157: 645-658. 10.1104/pp.111.180810.

Tabas I, Ron D: Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nature Cell Biol. 2011, 13: 184-190. 10.1038/ncb0311-184.

Distelhorst CW, McCormick TS: Bcl-2 acts subsequent to and independent of Ca2+ fluxes to inhibit apoptosis in thapsigargin- and glucocorticoid-treated mouse lymphoma cells. Cell Calcium. 1996, 19: 473-483. 10.1016/S0143-4160(96)90056-1.

Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ: Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001, 292: 727-730. 10.1126/science.1059108.

Crosti P, Malerba M, Bianchetti R: Tunicamycin and Brefeldin A induce in plant cells a programmed cell death showing apoptotic features. Protoplasma. 2001, 216: 31-38. 10.1007/BF02680128.

Kim M, Ahn J-W, Jin U-H, Choi D, Paek K-H, Pai H-S: Activation of the programmed cell death pathway by inhibition of proteasome function in plants. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 19406-19415. 10.1074/jbc.M210539200.

Ahn CS, Han J-A, Lee H-S, Lee S, Pai H-S: The PP2A regulatory subunit Tap46, a component of TOR signaling pathway, modulates growth and metabolism in plants. Plant Cell. 2011, 23: 185-209. 10.1105/tpc.110.074005.

Ratcliff F, Martin-Hernansez AM, Baulcombe DC: Tobacco rattle virus as a vector for analysis of gene function by silencing. Plant J. 2001, 25: 237-245.

Buzeli RA, Cascardo JC, Rodrigues LA, Andrade MO, Almeida RS, Loureiro ME, Otoni WC, Fontes EP: Tissue-specific regulation of BiP genes: a cis-acting regulatory domain is required for BiP promoter activity in plant meristems. Plant Mol Biol. 2002, 50: 757-771. 10.1023/A:1019994721545.

Lee JY, Lee HS, Wi SJ, Park KY, Schmit AC, Pai HS: Dual functions ofNicotiana benthamianaRae1 in interphase and mitosis. Plant J. 2009, 59: 278-291. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03869.x.

Sasabe M, Soyano T, Takahashi Y, Sonobe S, Igarashi H, Itoh TJ, Hidaka M, Machida Y: Phosphorylation of NtMAP65-1 by a MAP kinase down-regulates its activity of microtubule bundling and stimulates progression of cytokinesis of tobacco cells. Genes Dev. 2006, 20: 1004-1014. 10.1101/gad.1408106.

Jin JB, Kim YA, Kim SJ, Lee SH, Kim DH, Cheong GW, Hwang I: A new dynamin-like protein, ADL6, is involved in trafficking from the trans-Golgi network to the central vacuole inArabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001, 13: 1511-1526.

Min MK, Kim SJ, Miao Y, Shin J, Jiang L, Hwang I: Overexpression ofArabidopsisAGD7 causes relocation of Golgi-localized proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum and inhibits protein trafficking in plant cells. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143: 1601-1614. 10.1104/pp.106.095091.

Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D: An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushystunt virus. Plant J. 2003, 33: 949-956. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01676.x.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development [Project numbers PJ009079 (PMBC) and PJ008214 (SSAC)] from Rural Development Administration and the Mid-career Researcher Program (No. 2012047824) from National Research Foundation of Republic of Korea.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

J-YL and SS performed most of the experiments and analyzed the results. HSK performed the promoter-GUS assays. HK and IH performed the protein trafficking assays. YJK performed the histological analyses. IH and YJK discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. H-SP designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jae-Yong Lee, Sujon Sarowar contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12870_2013_1280_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Figure S1: NAG sequence alignment.Figure S2.Nuclear morphology and mitochondrial membrane integrity at 10 DAI.Figure S3.Ultrastructural analyses using transmission electron microscopy (TEM).Figure S4.Fluorescence microscope images of GFP:bZIP28 localization.Figure S5.Measurement of fluorescence intensity and band intensity. (PDF 874 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open AccessThis article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, JY., Sarowar, S., Kim, H.S.et al.Silencing ofNicotiana benthamiana Neuroblastoma-Amplified Genecauses ER stress and cell death.BMC Plant Biol13,69 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-13-69

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-13-69

Keywords

- bZIP28

- ER stress gene expression

- Promoter-GUS fusion

- Protein transport assay

- Virus-induced gene silencing