- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Characterization of phenylpropanoid pathway genes within European maize (Zea maysL.) inbreds

BMC Plant Biologyvolume8, Article number:2(2008)

Abstract

Background

Forage quality of maize is influenced by both the content and structure of lignins in the cell wall. Biosynthesis of monolignols, constituting the complex structure of lignins, is catalyzed by enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway.

Results

In the present study we have amplified partial genomic fragments of six putative phenylpropanoid pathway genes in a panel of elite European inbred lines of maize (Zea maysL.) contrasting in forage quality traits. Six loci, encoding C4H, 4CL1, 4CL2, C3H, F5H, and CAD, displayed different levels of nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium (LD) possibly reflecting different levels of selection. Associations with forage quality traits were identified for several individual polymorphisms within the4CL1,C3H, andF5Hgenomic fragments when controlling for both overall population structure and relative kinship. A 1-bp indel in4CL1was associated within vitrodigestibility of organic matter (IVDOM), a non-synonymous SNP inC3Hwas associated with IVDOM, and an intron SNP inF5Hwas associated with neutral detergent fiber. However, theC3HandF5Hassociations did not remain significant when controlling for multiple testing.

Conclusion

While the number of lines included in this study limit the power of the association analysis, our results imply that genetic variation for forage quality traits can be mined in phenylpropanoid pathway genes of elite breeding lines of maize.

Background

Maize (Zea maysL.) is widely used as a silage crop in European dairy agriculture. While breeding efforts in recent decades have substantially increased whole plant yield, there has been a decrease in cell wall digestibility, and consequently feeding value, of elite silage maize hybrids [1,2]。Digestibility of cell walls of forage crops is influenced by several factors, including the content and composition of lignins [3]。Lignins are complex phenolic polymers derived mainly from three hydroxycinnamyl alcohol monomers (monolignols):p-coumaryl-, coniferyl-, and sinapyl alcohol.p-hydroxyphenyl- (H), guaiacyl- (G), and syringyl units (S), respectively, are derived from these alcohols and polymerize by oxidation to form lignins. In monocots, lignins are predominantly comprised of G and S units [4]。

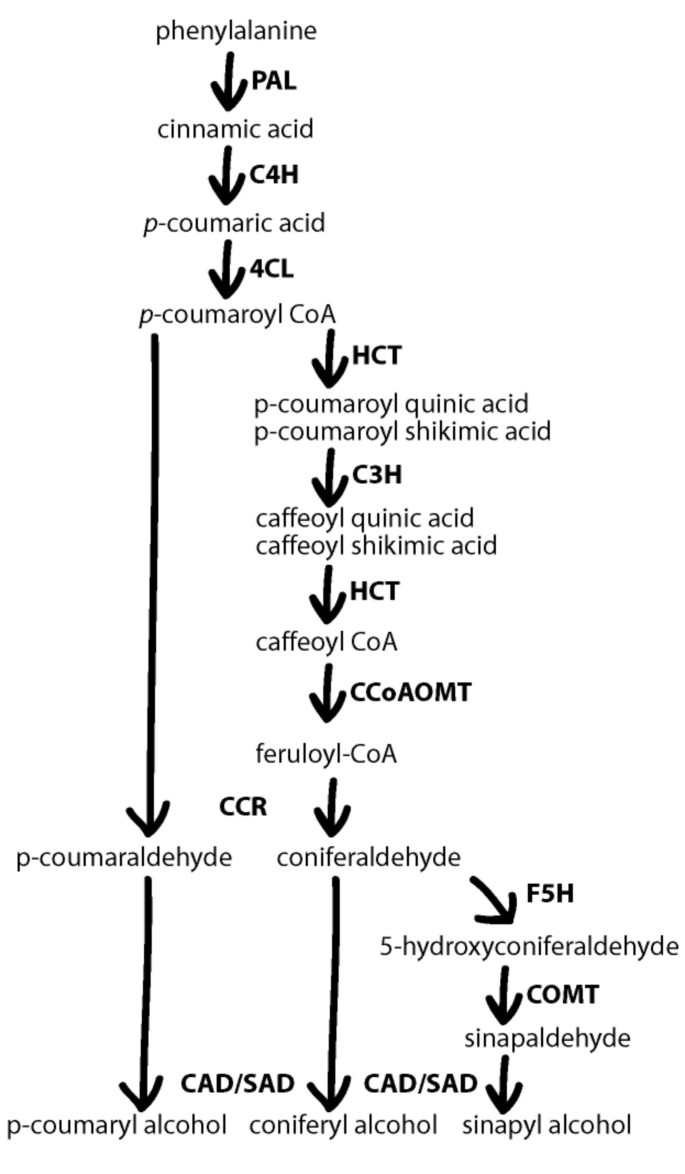

Biosynthesis of monolignols, and a variety of other secondary metabolites, is controlled by the phenylpropanoid pathway (Figure1).我的第一步phenylpropanoid通路s the deamination of L-phenylalanine by phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) to cinnamic acid. Subsequent enzymatic steps involving the actions of cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL), hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA transferase (HCT),p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase (C3H), caffeoyl-CoAO-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H), caffeic acidO-methyltransferase (COMT), and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) catalyze the biosynthesis of monolignols (Figure1).In maize, one or more genes encoding each of these enzymes have been cloned [5–12]。A recent comprehensive study has shown that almost all enzymes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway of maize, with the exception of C3H and COMT, are encoded by multigene families [8]。

的fourbrown-midrib(bm) mutants of maize are characterized by a decreased lignin content, an altered cell wall composition, and a brown-reddish colour of leaf midribs.bm1is caused by a severe decrease in CAD enzyme activity, possibly resulting from a decrease inCADtranscription [9,13],bm3is caused by a knock-out mutation in theCOMTgene [14,15], while the genes underlying thebm2andbm4mutations are unknown. Of the four knownbmmutants,bm3exhibits the strongest effect on plant phenotype, including a reduction in total lignin and an altered lignin composition [16]。A positive effect of thebm3mutant has been observed on intake and digestibility of forage maize [3]。然而,劣质农艺等性能lodging and lower biomass yield result from this mutation as well, restricting the use ofbm3mutants in maize breeding programs [17]。的bm1mutant is also characterized by a reduction in total lignin and an altered lignin composition [16]。Characterization of genetic diversity associated with forage quality traits in genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway might facilitate identification of alleles more applicable to breeding programs.

Levels of nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium (LD), and associations to forage quality traits have been reported for several genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway [18–21]。Due to population bottlenecks and selection, LD is generally higher among elite breeding lines than within distantly related germplasm [22]。与这个协议,延长LD,跨越from hundreds of kb to tens of cM, has been reported among elite inbred lines [23–26]。对比的LD曾被观察到的赌注ween genes in the phenylpropanoid pathway. While LD decreased rapidly within few hundred bp at theCOMTandCCoAOMT2loci [20,21], LD persisted over thousands of bp at aPALlocus [18]。的extent of LD is relevant in the context of association (LD) mapping as it determines both the marker saturation necessary for association mapping as well as the possibility to discriminate between phenotypic effects of individual polymorphisms. The first candidate gene-based association mapping study in plants, associating individualdwarf8polymorphisms with flowering time of maize [27], has been followed by numerous studies in maize [28] and other crop plants [29]。Associations between maize forage quality traits and individual polymorphisms have been reported for thePAL,CCoAOMT2, andCOMTgenes [18,20,30] as well as for theZmPox3maize peroxidase gene, putatively involved in the oxidative polymerization of monolignols [31,32]。Consequently, target sites within phenylpropanoid pathway genes for functional marker development [33] for forage quality traits have been identified.

In the present study, partial genomic sequences ofC4H,4CL1,4CL2,C3H,F5H, andCADwere obtained in a set of 40 European forage maize inbred lines. Since European elite material was included in this study, LD was expected to span whole genes. Therefore, sequencing efforts were directed towards obtaining partial sequences of several genes as compared to obtaining the full sequence(s) of one/few genes, the rationale being that this would increase the number of unlinked polymorphisms available for testing by subsequent association analysis in a broader range of materials. The objectives were to (1) examine nucleotide diversity within genes, (2) examine LD within and between genes, and (3) to test for associations between individual polymorphisms and three forage quality traits.

Results

Phenotypic data

Analysis of variance and phenotypic correlations were published previously [18]。Mean phenotypic values for individual lines across five environments ranged from 50.33 to 63.03 for neutral detergent fiber (NDF), 67.23 to 77.98 forin vitrodigestibility of organic matter (IVDOM), and 49.59 to 60.99 for digestibility of neutral detergent fiber (DNDF) (Table1).的least significant differences between lines were 3.71, 2.69, and 2.70 for NDF, IVDOM, and DNDF, respectively. Heritabilities were 86.5%, 89.5%, and 92.2% for NDF, IVDOM, and DNDF, respectively.

Nucleotide- and haplotype diversity and selection

Partial genomic fragments were amplified for six candidate genes (names in parenthesis refer to identical genes in the MAIZEWALL database [8]):C4H(C4H1),4CL1(4CL),4CL2(not identified),C3H(C3H),F5H(F5H1), andCAD(Y13733). The resulting alignments were from 461 bp (C4H) to 1,306 bp (4CL1) in length and were based on 16 (F5H) to 40 (C4H) lines (Table2).的exon-intron structure at individual loci was estimated by alignments to the mRNA sequences from which primers were developed. GENSCAN estimations supported the structures predicted by the alignments and all amplified sequences were predicted to include both coding and non-coding regions. A total of 54 SNPs were identified out of which 25 were non-redundant for discrimination of haplotypes. Total nucleotide diversity (π) ranged from 0.00049 at theCADlocus to 0.01025 at the4CL2locus, and Tajima's D did not indicate selection at any of the six loci (Table2).的number of haplotypes defined by SNPs ranged from two at theCADlocus (where only one SNP was identified), four at theC4Hand4CL1loci, five at theF5Hlocus, to seven at the4CL2andC3Hloci (Tables3,4,5,6,7,8).

Intra- and inter-locus linkage disequilibrium

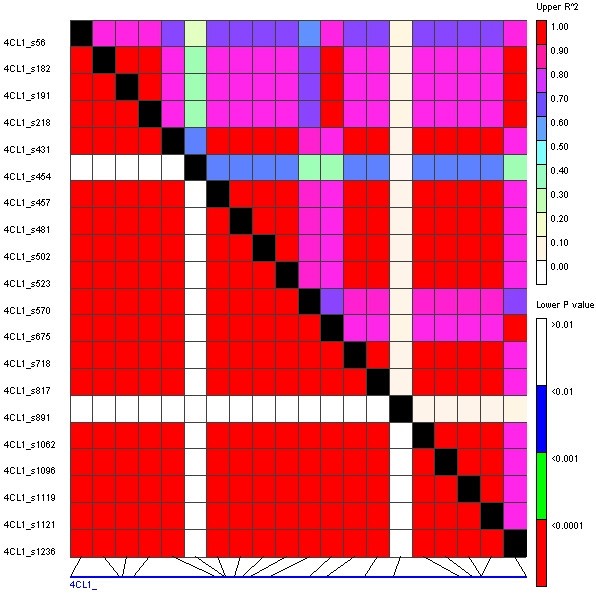

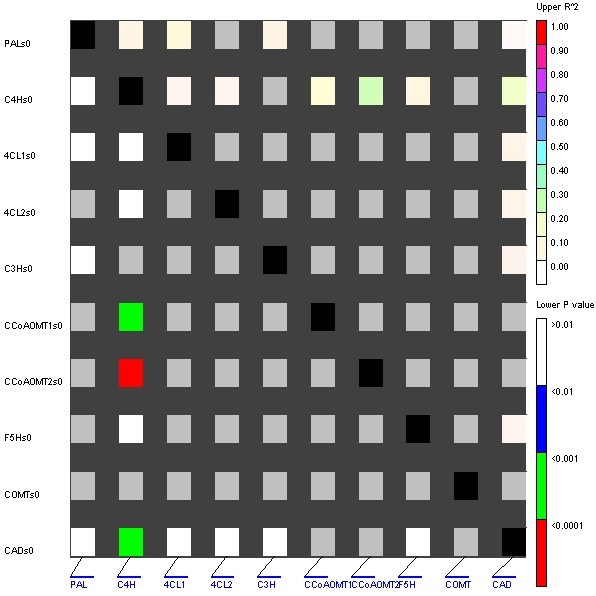

Extended LD was identified at the4CL1locus at which all polymorphisms, with the exception of two 1-bp deletions, were in high LD (P > 0.001) across the entire amplified sequence (~1.3 kb; Figure2).At theC4H,C3H,4CL2, andF5Hloci, breakdown of LD was observed within ~200 bp. Inter-locus LD was examined by estimating LD between SNP haplotypes of the six loci as well asPAL(32 lines),COMT(42 lines),CCoAOMT1(40 lines) andCCoAOMT2(34 lines) ([18,21], unpublished results). This revealed thatC4Hwere in high (P < 0.0001) LD withCCoAOMT2and intermediate (P < 0.001) LD withCCoAOMT1andCAD. Significant LD was not observed between any other pairs of loci (Figure3).Examining LD between individual SNPs at these three loci pinpointed that a single non-synonymous SNP, changing the 27thamino acid of the C4H enzyme from Threonine to Serine, was in high LD with several SNPs at theCCoAOMT1andCCoAOMT2locus, respectively (data not shown).

Population structure and marker-trait associations

WithinStructurewe evaluated whether the 40 lines constitute one, two, three, or four subpopulations, respectively. Two subpopulations (K= 2)是最有可能出现的情景(结果不是商店wn). Most lines were estimated to be > 99% Flint or Dent, in agreement with pedigree information. Under the assumption of two subpopulations, four lines showed approximate 3:1(AS27 and AS29) or 1:3 (AS34 and AS39) ratios of genetic background of Dent:Flint.

的estimated population structure matrix was included in the association analysis, performed as GLM analysis inTASSEL. At the4CL1locus a 1-bp indel was associated with NDF and IVDOM (Table9).插入等位基因存在于只有一个ne (AS18), which exhibits NDF = 61.43 compared to an overall mean of 56.25, and IVDOM = 67.95 compared to an overall mean of 73.30 (Table1).At theC3Hlocus, a non-synonymous G/C SNP at position 294 of the alignment was associated with both IVDOM and DNDF. The C allele was present in two lines (AS14 and AS28). While IVDOM and DNDF values for AS14 are slightly below the overall means, AS28 exhibits the lowest overall values for both IVDOM and DNDF, 67.23 and 49.59, respectively (Table1).At theF5Hlocus, two non-synonymous SNPs, at positions 5 and 6 and in complete LD, were associated with NDF. The G and C allele, respectively, of these two C/G SNPs were present in lines AS20 to AS24. The mean NDF value of these five lines is 52.96 compared to an overall mean of 56.25. The line AS23 is differing from the other four lines in this haplotype as it exhibits an NDF value above the overall mean (Table1).In addition, two SNPs in the intron region ofF5Hwere associated with DNDF (C/G SNP, position 610) and NDF (C/T SNP, position 817). At position 610 a singleton SNP was present in line AS24, exhibiting the highest overall DNDF value (Table1).At position 817, the C allele was present in lines AS14, AS15, and AS20 to AS22, the mean of these lines being below the overall mean of NDF. It should be noted that forF5H, only 16 lines was included in the sample. In addition, the SNP at position 817 was genotyped for only 13 lines due to an indel polymorphism in this region. Consequently, this SNP was not included in the haplotype overview (Table7).No associations with forage quality traits were detected for the4CL2,C4H, andCADgene fragments.

的associations identified by GLM were validated by the MLM method, which in addition to overall population structure also corrects for finer scale relative kinship. By MLM, significant associations (P < 0.05) of the4CL1indel with IVDOM, theC3HSNP with IVDOM, and oneF5Hintron SNP with NDF were identified (Table9).No association to DNDF was detected when correcting for both overall population structure and relative kinship. Controlling for multiple testing by the FDR method requires P < 0.005 to reject the hypothesis of no association. One association, identified by GLM analysis, satisfied this constraint: the association of the 1 bp frameshift indel in4CL1with IVDOM (P = 0.0017).

Discussion and conclusion

Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium in the phenylpropanoid pathway

In the present study, the partial genomic sequence of six genes putatively involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway has been obtained for 16 to 40 inbred lines of European maize. Population bottlenecks and selection are expected to decrease nucleotide diversity and increase LD at a given locus [22,23]。While selection was not indicated at any of the six loci (Table2) nucleotide diversity (π) varied considerably between loci, ranging from 0.00049 at theCADlocus to 0.01025 at the4CL2locus. Comparable levels of nucleotide diversity have been reported for other genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway within a similar and overlapping set of lines [18,21] as well as within a more diverse set of lines [20]。Also, a comprehensive study of six genes of the starch pathway of maize revealed similar levels of diversity [34]。Nucleotide diversity at theCADlocus is exceptionally low as compared to other phenylpropanoid pathway genes, with only one SNP identified across 38 genotypes (Table2).While theCADsequence is relatively short (~0.5 kb), several SNPs were identified within fragments of similar length for other genes (Table2).

Levels of LD varied between loci, spanning the full4CL1sequence (~1.3 kb) while decaying within few hundred bps at theC4H,C3H,4CL2, andF5Hloci. Due to population bottlenecks and selection, LD can be expected to be higher among elite breeding lines as compared to more distantly related germplasm. In agreement with this, a rapid LD decay (r2< 0.1 within few hundred bps) has been reported for several loci in diverse sets of maize germplasm [35,36] while extended LD, up to tens of cM, has been reported among elite inbred lines [23–26]。However, extended LD was also observed at thesugary1locus in a set of diverse germplam [35] indicating considerable variation in LD between loci regardless of sampled plant material. Varying levels of LD have previously been observed between genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway, decaying within few hundred bps forCCoAOMT2andCOMT[20,21] while spanning more than 3.5 kb at thePALlocus [18], supporting that LD decay is differentiating more between loci than between samples of different origin, e.g., between elite breeding lines and more distantly related germplams. In agreement with this, LD decay at theCOMTlocus was similar between a diverse set of lines (r2= 0.2 within ~250 bp) [20] and a set of elite European breeding lines (r2= 0.2 within ~500 bp) [21]。

Varying levels of nucleotide diversity and LD between loci could reflect different levels of constraints put on individual loci by selection. It might also be speculated that these parameters would be influenced by length of exons and introns contained in individual gene amplicons. However, levels of nucleotide diversity and LD did not seem to be correlated to exon:intron proportions of individual genes (Table2和数据未显示)。Nucleotide diversity at theCADlocus, encoding the enzyme catalyzing the last step in monolignol biosynthesis, the reduction ofp-hydroxycinnamaldehydes into their respective alcohols, is found to be exceptionally low, with only one SNP identified across the ~0.5 kb examined in this study. It should be noted that the level of nucleotide diversity identified here might not be indicative for theCADlocus as a whole. A recent comprehensive study of gene expression in relation to cell wall biosynthesis in maize identified a total of sevenCADgene family members, of which the one examined here was highly expressed in internodes [8]。In addition, reduced CAD enzyme activity and altered lignin content and structure were observed in thebm1mutant [9], most likely resulting from decreased expression of this and/or otherCADgenes [9,13]。Thus, an important role in lignification is indicated for thisCADgene, suggesting selection against detrimental mutations at this locus.

While nucleotide diversity at the4CL1locus was found to be ~10 fold higher than for theCADgene, all SNPs across the4CL1locus (~1.3 kb) were in high LD (Figure2).This is comparable to the situation at thePALlocus, at which all informative polymorphisms were in complete LD across ~2.5 kb within an overlapping sample of lines [18]。PAL is the first enzyme in several phenylpropanoid pathways, catalyzing the production of a number of phenylpropanoids, including monolignols, from phenylalanine. InArabidopsisit has been observed thatPALmutants were affected not only in the monolignol pathway, but that also carbohydrate- and amino acid metabolisms were altered [37]。While the 4CL enzyme is further downstream in the phenylpropanoid pathway, it is before the branching of the pathway into monolignol-, flavonoid- and other biosynthetic pathways. The4CL1gene investigated in the present study is highly expressed in leaves and young stems of maize [8], indicating an important function of the enzyme in these tissues. Thus, functional constraints of the enzyme might restrict recombination rates at the gene, resulting in the extended LD observed at the4CL1locus.

While LD decay was rapid within theC4Hgene, a single non-synonymous SNP inC4Hwas in high LD with several SNPs in theCCoAOMT1andCCoAOMT2genes, respectively. WhileC4His located on chromosome 8 (unpublished results), theCCoAOMT1andCCoAOMT2genes are located on chromosomes 6 and 9, respectively [20]。It could be speculated thatC4H,CCoAOMT1, andCCoAOMT2are epistatically interacting, i.e., particular allelic variants leading to altered C4H enzymes are dependent on specific allelic properties at the twoCCoAOMTloci. An expression-QTL for cell wall biosynthesis genes has been identified at bin 9.04 [38] nearCCoAOMT2at bin 9.02 [20]。Thus, given the limited precision of QTL mapping experiments, it could be speculated thatCCoAOMT2is involved, directly or indirectly, in the regulation of several cell wall biosynthesis genes.

Association of genetic variation in the phenylpropanoid pathway and forage quality

Previous studies have identified associations between phenylpropanoid pathway genes and forage quality traits [18,20,30]。In the present study we have identified associations between polymorphisms in4CL1,C3H, andF5Hand NDF, IVDOM, and/or DNDF, of which DNDF is the most relevant trait in relation to forage quality. No associations were detected for4CL2,C4H, andCADpolymorphisms. When correcting for multiple testing the association between4CL1and IVDOM remained significant. The4CL1gene investigated in the present study is homologous to the4CL1ofArabidopsis[39] and is highly expressed in leaves and young stems of maize [8]。InArabidopsis,4CL1has been shown to be involved in the biosynthesis of lignin, antisense lines being depleted in G monolignol units [40]。In the present study, a 1-bp indel in4CL1was found to be associated with IVDOM by both GLM and MLM. The insertion allele of this indel is present in only one line, AS18, which exhibits the second lowest overall value of IVDOM. The insertion results in a frameshift in the first exon, introducing a premature stop codon four amino acids downstream the insertion. It is thus likely that this indel directly influences the function of the 4CL1 enzyme. In relation to association analysis the situation of a single phenotypically extreme individual is a potential problem. This individual might show numerous specific mutations, which consequently would show association to the phenotype if tested. In the present study, associations based on one/few phenotypically extreme individuals could explain why associations are identified to IVDOM and not to DNDF, andvice versa, in spite of these two traits being highly correlated [18]。Including population structure and kinship into association analysis reduces the number of false positive associations. However, associations based on single phenotypically extreme individuals should be considered with caution and validated in broader plant material.

While not significant when controlling for multiple testing, a non-synonymous SNP in the terminal exon ofC3Hwas associated with IVDOM by both GLM and MLM. The C allele of this G/C SNP was identified in two lines of which AS28 exhibits the lowest overall values of both IVDOM and DNDF. InArabidopsis[41] and maize [8], a singleC3Hgene has been identified, which in maize is expressed in relatively low levels in different tissues [8]。A reduced transcription ofC3Hhas been shown to affect lignin content and composition in bothArabidopsis[42] and alfalfa [43]。Moreover, alfalfa lines down-regulated inC3Htranscription exhibited increasedin vitrodry matter digestibility (IVDMD) [44]。Given a similar function of the C3H enzyme in maize, allelic variation at this locus might directly affect lignin content and composition and in turn digestibility of the maize cell wall.

At theF5Hgene, a SNP in the intron was associated with NDF by both GLM and MLM, but not when controlling for multiple testing. TwoF5Hgenes have been identified in bothArabidopsis[45,46] and maize [8,11]。InArabidopsis[47] and alfalfa [44], plants deficient inF5Htranscription exhibit an altered composition of lignin. However, an effect on NDF or IVDMD was not observed inF5Hdown-regulated lines of alfalfa [44]。在玉米,F5Hgene analyzed in this study is highly expressed in young stems and in leaves [8]。It can be questioned if a SNP in the intron region has a causative effect on phenotypic traits. However, this SNP might be in LD with causative variation in other regions of the ORF.

One of the factors greatly affecting the outcome of the association analysis is the choice of method for testing associations (Table9) [28,48]。By correcting for overall population structure (Q) ten significant associations were identified, five of which were confirmed when including correction for relative kinship (K). No additional associations were identified when correcting for both Q and K as compared to when correcting only for Q. Not surprisingly, a greater number of associations were identified when no correction for population structure was made (data not shown). It has been shown that the number of false positive associations is reduced when controlling Q and, to a greater extend, when controlling for both Q and K [48]。However, both trait values and causative polymorphisms might be confounded with population structure, e.g., between Flint and Dent lines. In consequence, true positive associations might not be identified by association analysis when considering population structure. To avoid this, it might be beneficial (if possible) to ensure an even distribution of trait values within and between subpopulations in the plant genotype sample employed for association analysis. Independent of the method, sample size is an important factor and, in the present study, a limiting factor in relation to association analyses. Consequently, the associations reported here should be considered indicative and validated in a larger sample of lines before applied in, e.g., breeding programs. In addition, due to the limited extent of LD at four out of six genes, full-length sequences of these genes would likely increase the number of unlinked polymorphisms to be tested for associations.

Deriving functional markers for forage quality traits

With the results presented here, genes encoding most of the enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway in maize have been tested for association with forage quality traits. ThePALgene was investigated in a set of 32 European elite inbred lines, overlapping with the lines used in this study [18]。A 1-bp deletion in the second exon ofPAL, introducing a premature stop codon, was associated with high IVDOM. TwoCCoAOMTgenes have been investigated in a set of 34 diverse lines used in both European and US breeding programs [20]。While no associations were detected forCCoAOMT1, an SSR-like insertion in the first exon ofCCoAOMT2was associated with an increase in cell wall digestibility. For theCOMTgene, indel polymorphisms in the intron region have been associated with cell wall digestibility in two different sets of lines, one of which are overlapping with the set employed in the present study [20,30]。Specifically, a 1-bp deletion in a putative splice site recognition site was associated with high cell wall digestibility [20]。Likewise, a MITE insertion in the second exon of theZmPox3gene, encoding a peroxidase putatively involved in monolignol polymerization, was associated with high cell wall digestibility [32]。

Combining previous results with the results reported in the present study, it seems likely that several genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway can be considered candidate genes for deriving functional markers for forage quality. In addition, it is indicated that useful variation in these genes can be identified even within elite breeding lines of maize, although alleles with larger effects on phenotype might be mined from a broader and larger sample of lines. Polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes downstream in the phenylpropanoid pathway have been indicated to increase cell wall digestibility [20,30,32], while similar polymorphisms have been associated with increase and decrease in IVDOM forPAL[18] and4CL1(Table9), respectively. It could be speculated that genes more downstream in the phenylpropanoid pathway (Figure1) would make more suitable targets for functional marker development in relation to digestibility of the cell wall. Such genes might be more specific to lignin biosynthesis as compared to genes acting earlier in the phenylpropanoid pathway, which could possibly affect several pathways as illustrated byPALinArabidopsis[37]。However, the recent identification of gene families in most genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway in maize [8] might suggest that specialization towards biosynthesis of lignin occur earlier in the phenylpropanoid pathway than previously assumed.

Methods

Plant materials and phenotypic analyses

A collection of 40 maize inbred lines consisting of 22 Flint and 18 Dent lines were included in this analysis. The line collection is identical to the one published previously [18], with the addition of eight lines. Thirty-five lines were from the current breeding program of KWS Saat AG and five lines were from the public domain (AS01, AS02, AS03, AS39, and AS40 identical to F7, F2, EP1, F288, and F4, respectively; Table1).选择是基于这组行DNDF values to represent a broad range of variability for this trait in central European germplasm employed in forage maize breeding. The included lines were derived from different Flint and Dent breeding populations, respectively, and are not related by descent apart from lines AS20 and AS21 which form an isogenic line pair differing for DNDF. The inbred lines were evaluated in Grucking (sandy loam) in 2002, 2003, and 2004, and in Bernburg (sandy loam) in 2003 and 2004. The experiments included 49 entries in a 7 × 7 lattice design with two replications. Plots consisted of single rows, 0.75 m apart and 3 m long with a total of 20 plants. About 50 days after flowering the ears were manually removed and the stover was chopped. Approximately 1 kg of the material was collected and dried at 40°C. The stover was ground to pass through a 1 mm sieve. Quality analyses were performed with near infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS) based on previous calibrations on the data of 300 inbred lines (unpublished results). The following data were recorded: NDF [49], IVDOM [50], and DNDF given by the formula DNDF = 100 - (100 - IVDOM)/(NDF × DM/OM/100) where DM is dry matter content and OM is organic matter content of the sample.

DNA isolation, PCR amplification, and DNA sequencing

Plants were grown for DNA isolation in the greenhouse and leaves were harvested at three weeks after germination. Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves using the Maxi CTAB method [51]。Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers were developed for six candidate genes (C4H,4CL1,4CL2,C3H,F5H, andCAD) based on maize mRNA sequences identified in GenBank (Table10) by BLASTing [52] known phenylpropaniod pathway genes. PCR reactions contained 20 ng genomic DNA, primers (200 nM), dNTPs (200 μM), 1 M Betain and 2 units of Taq polymerase (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. A touchdown PCR program was applied as follows: an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 2 min, 15 amplification cycles: 45 sec at 95°C; 45 sec at 68°C (minus 0.5°C per cycle), 2 min at 72°C, followed by 24 amplification cycles: 45 sec at 95°C; 45 sec at 60°C, 2 min at 72°C, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. Products were separated by gel electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels, visualized by ethidium bromide staining and photographed using an eagle eye apparatus (Herolab, Wiesloch, Germany).

Amplicons were purified using QiaQuick spin columns (Qiagen, Valencia, USA) according to the manufacturers instructions, and sequenced directly using internal sequence specific primers and the Big Dye1.1 dye-terminator sequencing kit on an ABI 377 (PE Biosystems, Foster City, USA). Electropherograms of overlapping sequencing fragments were manually edited using the software package Sequence Navigator version 1.1 from PE Biosystems. Full alignments were built up using default settings of the Clustal program version 1.8 [53] followed by manual refinement to minimize the number of gaps.

Analysis of sequence data

的exon-intron structure of the amplified genomic sequences was estimated by alignment to the mRNA sequences used for primer development (Table10) and validated by the GENSCAN web server at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [54]。

Nucleotide diversity (π), the average number of nucleotide differences per site between two sequences was estimated by using DNASP Version 4.10 [55]。Indel polymorphisms were excluded from the estimates ofπ. Tajima's D statistic [56] was also estimated by DNASP to test for selection at individual loci. LD between pairs of polymorphic sites (SNPs and indels, excluding singletons) within and between loci was estimated by the TASSEL software, version 1.9.0 [27,57]。Various measurements for LD have been developed [58] of which squared allele frequency correlations (r2) [59] were chosen for our calculations. The significance of LD between sites was tested by Fisher's exact test. For the estimation of inter-locus LD, the alignments ofPAL,COMT,CCoAOMT1, andCCoAOMT2([18,21], unpublished results) were included.

Population structure and association analysis

Lines were genotyped with 101 simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs) providing an even coverage of the maize genome. The employed SSR markers are publicly available [60]。Population structure was inferred from the SSR data by theStructure2.0 software [61,62]。Structureapplies a Bayesian clustering approach to group individual lines in subpopulations based on marker profiles. A Q matrix is produced that lists the estimated membership coefficients for each individual in each subpopulation. A burn-in length of 50.000 followed by 50.000 iterations was used. The Admixture model was applied with independent allele frequencies. Data were defined as haploid.

Association analysis was carried out as a general linear model (GLM) analysis inTASSELto test for associations between individual polymorphisms and mean phenotypic values across five environments (Table1).的Q matrix produced byStructurewas included as covariate in the analysis to control for populations structure. All polymorphisms (including singletons) were tested and the P-value for individual polymorphisms was estimated based on 10,000 permutations of the dataset. Associations were further tested by the unified mixed model method for association mapping (MLM) inTASSEL[48]。的MLM simultaneously accounts for overall population structure (Q) and finer scale relative kinship (K). Loiselle kinship coefficients [63] between lines (a K matrix) were estimated by the SPAGeDI software [64] based on the SSR data mentioned above. Negative values between two individuals in the K matrix were set to 0 as a negative value indicates that two individuals are less related that random individuals [64]。的diagonal of the K matrix were assigned the value 2. The False Discovery Rate (FDR) method [65] was applied to correct for multiple testing.

Abbreviations

- 4CL:

-

4-coumarate:CoA ligase, C3H:p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase, C4H cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, CAD: cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase, CCoAOMT: caffeoyl-CoAO:-methyltransferase, COMT: caffeic acidO-methyltransferase, DNDF digestibility of neutral detergent fiber, F5H: ferulate 5-hydroxylase, indel: insertion-deletion polymorphism, IVDOM:in vitro:digestibility of organic matter, LD: linkage disequilibrium, NDF: neutral detergent fiber, PAL: phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, SNP: single-nucleotide polymorphism

References

- 1.

Barrière Y, Emile JC, Traineau R, Surault F, Briand M, Gallais A: Genetic variation for organic matter and cell wall digestibility in silage maize. Lessons from a 34-year long experiment with sheep in digestibility crates. Maydica. 2004, 49: 115-126.

- 2.

Barrière Y, Alber D, Dolstra O, Lapierre C, Motto M, Ordas A, Van Waes J, Vlasminkel L, Welcker C, Monod JP: Past and prospects of forage maize breeding in Europe. I. The grass cell wall as a basis of genetic variation and future improvements in feeding value. Maydica. 2005, 50: 259-274.

- 3.

Barrière Y, Guillet C, Goffner D, Pichon M: Genetic variation and breeding strategies for improved cell wall digestibility in annual forage crops. A review. Anim Res. 2003, 52: 193-228. 10.1051/animres:2003018.

- 4.

Boerjan W, Ralph J, Baucher M: Lignin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003, 54: 519-546. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938.

- 5.

Civardi L, Rigau J, Puigdomènech P: Nucleotide Sequence of two cDNAs coding for Caffeoyl-coenzyme A O-Methyltransferase (CCoAOMT) and study of their expression in Zea mays. Plant Physiol. 1999, 120: 1026-113.

- 6.

Collazo P, Montoliu L, Puigdomenech P, Rigau J: Structure and expression of the ligninO-methyltransferase gene fromZea maysL. Plant Mol Biol. 1992, 20: 857-867. 10.1007/BF00027157.

- 7.

Gardiner J, Schroeder S, Polacco ML, Sanchez-Villeda H, Fang Z, Morgante M, Landewe T, Fengler K, Useche F, Hanafey M, Tingey S, Chou H, Wing R, Soderlund C, Coe EH: Anchoring 9,371 maize expressed sequence tagged unigenes to the Bacterial Artificial Chromosome Contig Map by Two-Dimensional Overgo Hybridization. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134: 1317-1326. 10.1104/pp.103.034538.

- 8.

圣克莱门特Guillaumie年代,H, Deswarte C,马丁内斯Y, Lapierre C, Murigneux A, Barrière Y, Pichon M, Goffner D: MAIZEWALL. Database and developmental gene expression profiling of cell wall biosynthesis and assembly in maize. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143: 339-363. 10.1104/pp.106.086405.

- 9.

Halpin C, Holt K, Chojecki J, Oliver D, Chabbert B, Monties B, Edwards K, Barakate A, Foxon GA: Brown-midrib maize (bm1) – a mutation affecting the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene. Plant J. 1998, 14: 545-553. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00153.x.

- 10.

Pichon M, Courbou I, Beckert M, Boudet A-M, Grima-Pettenati J: Cloning and characterization of two maize cDNAs encoding Cinnamoyl-CoA Reductase (CCR) and differential expression of the corresponding genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1998, 38: 671-676. 10.1023/A:1006060101866.

- 11.

Puigdomenech PC, Perez P, Murigneux A, Martinant JP, Tixier MH, Rigau J, Civardi L, Maes T: Identifying genes associated with a QTL corn digestibility locus. Patent. 2001, WO 0155395-A

- 12.

Rosler J, Krekel F, Amrhein N, Schmid J: Maize phenylalanine ammonia-lyase has tyrosine ammonia-lyase activity. Plant Physiol. 1997, 113: 175-179. 10.1104/pp.113.1.175.

- 13.

Guillaumie S, Pichon M, Martinant J-P, Bosio M, Goffner D, Barrière Y: Differential expression of phenylpropanoid and related genes in brown-midribbm1,bm2,bm3, andbm4young near-isogenic maize plants. Planta. 2007, 226: 235-250. 10.1007/s00425-006-0468-9.

- 14.

Morrow SL, Mascia P, Self KA, Altschuler M: Molecular characterization of a brown midrib3 deletion mutation in maize. Mol Breed. 1997, 3: 351-357. 10.1023/A:1009606422975.

- 15.

Vignols F, Rigau J, Torres MA, Capellades M, Puigdomenech P: The brown midrib3 (bm3) Mutation in Maize Occurs in the Gene Encoding Caffeic Acid O-Methyltransferase. Plant Cell. 1995, 7: 407-416. 10.1105/tpc.7.4.407.

- 16.

Barrière Y, Ralph J, Mechin V, Guillaumie S, Grabber JH, Argillier O, Chabbert B, Lapierre C: Genetic and molecular basis of grass cell wall biosynthesis and degradability. II. Lessons from brown-midrib mutants. CR Biol. 2004, 327: 847-860. 10.1016/j.crvi.2004.05.010.

- 17.

Cherney JH, Cherney DJR, Akin DE, Axtell JD: Potential of brown-midrib, low-lignin mutants for improving forage quality. Adv Agron. 1991, 46: 157-198.

- 18.

Andersen JR, Zein I, Wenzel G, Krützfeldt B, Eder J, Ouzunova M, Lübberstedt T: High levels of linkage disequilibrium and associations with forage quality at a Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase locus in European maize (Zea mays L.) inbreds. Theor Appl Genet. 2007, 114: 307-319. 10.1007/s00122-006-0434-8.

- 19.

Fontaine AS, Barrière Y: Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase allelic polymorphism characterization and analysis in different maize inbred lines. Mol Breed. 2003, 11: 69-75. 10.1023/A:1022116812041.

- 20.

Manicacci Guillet-Claude C, Birolleau-Touchard CD, Fourmann M, Barraud S, Carret V, Martinant JP, Barrière Y: Genetic diversity associated with variation in silage corn digestibility for threeO-methyltransferase genes involved in lignin biosynthesis. Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 110: 126-135. 10.1007/s00122-004-1808-4.

- 21.

Zein I, Wenzel G, Andersen JR, Lübberstedt T: Low Level of Linkage Disequilibrium at the COMT (Caffeic Acid O-methyl Transferase) Locus in European Maize (Zea mays L.). Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2007, 54: 139-148. 10.1007/s10722-005-2637-2.

- 22.

Flint-Garcia SA, Thornsberry JM, Buckler ES: Structure of linkage disequlibrium in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003, 54: 357-374. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134907.

- 23.

Ching A, Caldwell KS, Jung M, Dolan M, Smith OS, Tingey S, Morgante M, Rafalski AJ: SNP frequency, haplotype structure and linkage disequilibrium in elite maize inbred lines. BMC Genet. 2002, 3: 19-10.1186/1471-2156-3-19.

- 24.

Jung M, Ching A, Bhattramakki D, Dolan M, Tingey S, Morgante M, Rafalski A: Linkage disequilibrium and sequence diversity in a 500-kbp region around theadh1locus in elite maize germplasm. Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 109: 681-689. 10.1007/s00122-004-1695-8.

- 25.

Stich B, Melchinger AE, Frisch M, Maurer HP, Heckenberger M, Reif JC: Linkage disequilibrium in European elite maize germplasm investigated with SSRs. Theor Appl Genet. 2005, 111: 723-730. 10.1007/s00122-005-2057-x.

- 26.

Stich B, Maurer HP, Melchinger AE, Frisch M, Heckenberger M, van der Voort JR, Peleman J, Sørensen AP, Reif JC: Comparison of linkage disequlibrium in elite European maize inbred lines using AFLP and SSR markers. Mol Breed. 2006, 17: 217-226. 10.1007/s11032-005-5296-2.

- 27.

Thornsberry JM, Goodman MM, Doebley J, Kresovich S, Nielsen D, Buckler ES: Dwarf8 polymorphisms associate with variation in flowering time. Nat Genet. 2001, 28: 286-289. 10.1038/90135.

- 28.

Yu J, Buckler ES: Genetic association mapping and genome organization of maize. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006, 17 (2): 155-160.

- 29.

Gupta PK, Rustgi S, Kulwal PL: Linkage disequilibrium and association studies in higher plants: Present status and future prospects. Plant Mol Biol. 2005, 57: 461-485. 10.1007/s11103-005-0257-z.

- 30.

Lübberstedt T, Zein I, Andersen JR, Wenzel G, Krützfeldt B, Eder J, Ouzunova M, Chun S: Development and application of functional markers in maize. Euphytica. 2005, 146: 101-108. 10.1007/s10681-005-0892-0.

- 31.

de Obeso M, Caparros-Ruiz D, Vignols F, Puigdomenech P, Rigau J: Characterisation of maize peroxidases having differential patterns of mRNA accumulation in relation to lignifying tissues. Gene. 2003, 309: 23-33. 10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00462-1.

- 32.

Manicacci Guillet-Claude C, Birolleau-Touchard CD, Rogowsky P, Rigau J, Murigneux A, Martinant JP, Barrière Y: Nucleotide diversity of the ZmPox3 maize peroxidase gene: Relationships between a MITE insertion in exon 2 and variation in forage maize digestibility. BMC Genet. 2004, 5: 19-10.1186/1471-2156-5-19.

- 33.

Andersen JR, Lübberstedt T: Functional markers in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8: 554-560. 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.09.010.

- 34.

Whitt SR, Wilson LM, Tenaillon MI, Gaut BS, Buckler ES: Genetic diversity and selection in the maize starch pathway. PNAS. 2002, 99: 12959-12962. 10.1073/pnas.202476999.

- 35.

Remington DL, Thornsberry JM, Matsuoka Y, Wilson LM, Whitt SR, Doebley J, Kresovich S, Goodman MM, Buckler ES: Structure of linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic associations in the maize genome. PNAS. 2001, 98: 11479-11484. 10.1073/pnas.201394398.

- 36.

Tenaillon MI, Sawkins MC, Long AD, Gaut RL, Doebley JF, Gaut BS: Patterns of DNA sequence polymorphism along chromosome 1 of maize (Zea mays ssp. mays L.). PNAS. 2001, 98: 9161-9166. 10.1073/pnas.151244298.

- 37.

Rohde A, Morreel K, Ralph J, Goeminne G, Hostyn V, De Rycke R, Kushnir S, Van Doorsselaere J, Joseleau JP, Vuylsteke M, Van Driessche G, Van Beeumen J, Messens E, Boerjan W: Molecular phenotyping of the pal1 and pal2 mutants of arabidopsis thaliana reveals far-reaching consequences on phenylpropanoid, amino acid, and carbohydrate metabolism. Plant Cell. 2004, 16: 2749-2771. 10.1105/tpc.104.023705.

- 38.

Shi C, Uzarowska A, Ouzunova M, Landbeck M, Wenzel G, Lübberstedt T: Identification of candidate genes associated with cell wall digestibility and eQTL (expression quantitative trait loci) analysis in a Flint × Flint maize recombinant inbred line population. BMC Genomics. 2007, 8: 22-10.1186/1471-2164-8-22.

- 39.

Lee D, Ellard M, Wanner LA, Davis KR, Douglas CJ: TheArabidopsis4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL) gene: Stress and developmentally regulated expression and nucleotide sequence of its cDNA. Plant Mol Biol. 1995, 28: 871-884. 10.1007/BF00042072.

- 40.

Lee D, Meyer K, Chapple C, Douglas CJ: Antisense Suppression of 4-Coumarate:Coenzyme A Ligase Activity in Arabidopsis Leads to Altered Lignin Subunit Composition. Plant Cell. 1997, 9: 1985-1998. 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1985.

- 41.

Franke R, Hemm MR, Denault JW, Ruegger MO, Humphreys JM, Chapple C: The Arabidopsis REF8 gene encodes the 3-hydroxylase of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant J. 2002, 30: 33-45. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01266.x.

- 42.

Franke R, Humphreys JM, Hemm MR, Denault JW, Ruegger MO, Cusumano JC, Chapple C: Changes in secondary metabolism and deposition of an unusual lignin in the ref8 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002, 30: 47-59. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01267.x.

- 43.

Ralph J, Akiyama T, Kim H, Lu F, Schatz PF, Marita JM, Ralph SA, Reddy MSS, Chen F, Dixon RA: Effects of Coumarate 3-Hydroxylase Down-regulation on Lignin Structure. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 8843-8853. 10.1074/jbc.M511598200.

- 44.

Reddy MSS, Chen F, Shadle G, Jackson L, Aljoe H, Dixon RA: Targeted down-regulation of cytochrome P450 enzymes for forage quality improvement in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). PNAS. 2005, 102: 16573-16578. 10.1073/pnas.0505749102.

- 45.

Meyer K, Cusumano JC, Sommerville C, Chapple CCS: Ferulate-5-hydroxylase from Arabidopsis thaliana defines a new family of cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases. PNAS. 1996, 95: 6619-6623. 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6619.

- 46.

Raes J, Rohde A, Christensen JH, Van de Peer Y, Boerjan W: Genome-Wide Characterization of the Lignification Toolbox in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133: 1051-1071. 10.1104/pp.103.026484.

- 47.

Marita JM, Ralph J, Hatfield RD, Chapple C: NMR characterization of lignins in Arabidopsis altered in the activity of ferulate 5-hydroxylase. PNAS. 1999, 96: 12328-12332. 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12328.

- 48.

Yu JM, Pressoir G, Briggs WH, Bi IV, Yamasaki M, Doebley JF, McMullen MD, Gaut BS, Nielsen DM, Holland JB, Kresovich S, Buckler ES: A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat Genet. 2006, 38: 203-208. 10.1038/ng1702.

- 49.

Van Soest PJ: Use of detergents in analysis of fibrous feeds. II. A rapid method for determination of fiber and lignin. J Assoc Off Agric Cehm. 1963, 46: 829-835.

- 50.

Tilley JMA, Terry RA: A two stage technique forin vitrodigestion of forage crops. J Brit Grassl Soc. 1963, 18: 104-111.

- 51.

Saghai-Maroof MA, Soliman KM, Jorgensen RA, Allard RW: Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: Mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. PNAS. 1984, 81: 8014-8018. 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014.

- 52.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215: 403-410.

- 53.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22: 4673-4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

- 54.

- 55.

Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R: DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19: 2496-2497. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359.

- 56.

Tajima F: The effect of change in population size on DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989, 123: 597-601.

- 57.

[http://www2.maizegenetics.net/index.php?page=bioinformatics/tassel/index.html]

- 58.

Gaut BS, Long AD: The lowdown on linkage disequilibrium. Plant Cell. 2003, 15: 1502-1506. 10.1105/tpc.150730.

- 59.

Weir BS: Genetic Data Analysis II. Sunderland: Sinauer; 1996,

- 60.

- 61.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P: Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data. Genetics. 2000, 155: 945-959.

- 62.

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK: Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003, 164: 1567-1587.

- 63.

Loiselle BA, Sork VL, Nason J, Graham C: Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understory shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). Am J Bot. 1995, 82: 1420-1425. 10.2307/2445869.

- 64.

Hardy OJ, Vekemans X: spagedi: a versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol Ecol Notes. 2002, 2: 618-620. 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2002.00305.x.

- 65.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995, 57: 289-300.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank KWS Saat AG (Einbeck) and the German ministry for education and science (BMBF) for financial support of the EUREKA project Cerequal.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JRA performed the data analysis and prepared the manuscript. IZ carried out allele sequencing. GW contributed to experimental design. BD and JE provided phenotypic data. MO provided the SSR data and together with GW contributed to experimental design. TL coordinated the project and together with JRA prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jeppe Reitan Andersen, Imad Zein contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open AccessThis article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, J.R., Zein, I., Wenzel, G.et al.Characterization of phenylpropanoid pathway genes within European maize (Zea maysL.) inbreds.BMC Plant Biol8,2 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-8-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-8-2

Keywords

- Linkage Disequilibrium

- Phenylalanine Ammonia Lyase

- Neutral Detergent Fiber

- Phenylpropanoid Pathway

- Cinnamyl Alcohol Dehydrogenase