- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Independent and interactive effects of DOF affecting germination 1 (DAG1) and the Della proteins GA insensitive (GAI) and Repressor ofga1-3(RGA) in embryo development and seed germination

BMC Plant Biologyvolume14, Article number:200(2014)

Abstract

Background

The transcription factor DOF AFFECTING GERMINATION1 (DAG1) is a repressor of seed germination acting downstream of the master repressor PHYTOCROME INTERACTING FACTOR3-LIKE 5 (PIL5). Among others, PIL5 induces the expression of the genes encoding the two DELLA proteins GA INSENSITIVE 1 (GAI) and REPRESSOR OFga1-3(RGA).

Results

Based on the properties ofgai-t6andrga28mutant seeds, we show here that the absence of RGA severely increases dormancy, while lack of GAI only partially compensatesRGAinactivation. In addition, the germination properties of thedag1rga28double mutant are different from those of thedag1andrga28single mutants, suggesting that RGA and DAG1 act in independent branches of the PIL5-controlled germination pathway. Surprisingly, thedag1gai-t6double mutant proved embryo-lethal, suggesting an unexpected involvement of (a possible complex between) DAG1 and GAI in embryo development.

Conclusions

Rather than overlapping functions as previously suggested, we show that RGA and GAI play distinct roles in seed germination, and that GAI interacts with DAG1 in embryo development.

Background

Seed germination is controlled by multiple endogenous and environmental factors [1], which are integrated to trigger this developmental process at the right time. Two plant hormones play important roles in seed germination: gibberellins (GA), which have an inductive effect, and abscissic acid (ABA), which inhibits the process [2]. Several physical factors affect seed germination, such as light, temperature and water potential. The effect of light is mediated mainly by the photoreceptor phytochrome B (phyB) [3], and the levels of GA and ABA are oppositely modulated by light, which induces GA biosynthesis and causes a reduction in ABA levels [4],[5]. Among the regulators involved in phyB-mediated GA-induced seed germination in Arabidopsis, the bHLH transcription factor PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 3-LIKE 5 (PIL5) represents the master repressor [6]. In seeds kept in the darkness, PIL5 activates transcription ofGA-INSENSITIVE(GAI) andREPRESSOR OF ga1-3(RGA) [7], two nuclear-localized DELLA transcriptional regulators that repress GA-mediated responses and are rapidly degraded in response to GA [8]–[10]. Indeed, it has been shown that in Arabidopsis all DELLA proteins are under negative control by GA and the proteasome [11]. Accordingly, gain-of-functiondellamutants show GA-insensitive phenotypes (i.e. dwarfism), whereas loss-of-function mutations result in GA-hypersensitive phenotypes (e.g. increased height) [12].

The DELLA proteins represent a subfamily of the GRAS plant transcription factors, and are characterized by the N-terminal DELLA domain. In Arabidopsis there are fiveDELLAgenes: the above mentionedGAIandRGA,andRGA-LIKE 1,2,3(RGL 1,2,3). An insertional mutagenesis approach enabled cloning of ArabidopsisGAIby isolation of a Ds transposon-mutatedgai-t6allele [13], whileRGAwas identified by loss-of-function mutations [14] and shown to encode a protein closely related to GAI [15]. GAI and RGA were shown to have overlapping functions in repressing many growth processes, such as leaf expansion, stem elongation, floral initiation and seed germination [16],[17]. Moreover, double mutant seeds have a higher germination rate than the wild-type ones in response to increasing Red (R) light fluences [7].

As of other DELLA proteins involved in seed germination, RGL2 also plays a negative key role: genetic data clearly showed that only a combination ofrgaandrgl2orgai-t6andrgl2mutant alleles could restore seed germination in aga1-3background [18].

We have previously shown that the DOF transcription factor DAG1 (DOF AFFECTING GERMINATION1) is a repressor of seed germination in Arabidopsis:dag1knock-out mutant seeds require lower GA and R light fluence rates than wild-type seeds to germinate [19]–[21]. We have also pointed out that DAG1 acts in the phyB-mediated pathway:DAG1expression is reduced in seeds irradiated for 24 hours with R light, and this reduction is dependent on PIL5; inpil5mutant seedsDAG1expression is reduced irrespective of light conditions, indicating that DAG1 acts downstream of PIL5; moreover, DAG1 negatively regulates GA biosynthesis by directly repressing the GA biosynthetic geneAtGA3ox1[22]. Very recently, we demonstrated that GAI cooperates with DAG1 in repressingAtGA3ox1, and that it directly interacts with DAG1 [23].

In order to further clarify the role of DAG1 in phyB-mediated seed germination, we focus here on the functional relationship between DAG1, RGA and GAI in the control of this process. We provide genetic and phenotypic evidence suggesting different roles of the two DELLA proteins in seed germination and with respect to DAG1.

Results

Thegai-t6andrga28mutant alleles show different seed germination phenotypes

It has been reported that concurrent inactivation of bothGAIandRGAincreases the seed germination potential:gai-t6rga28double mutant seeds require less R light fluences than wild-type ones to germinate [7] - a phenotype that is reminiscent ofdag1mutant seeds, which need a fluence rate six times lower than wild-type to germinate [20]. We compared the seed germination properties of stored (28 days after ripening, DAR)gai-t6, rga28,double mutantgai-t6rga28and Col-0 wild-type seeds, under phyB-dependent germination conditions [7],[22]. We also assessed the germination properties under white light and in the dark, with or without stratification.

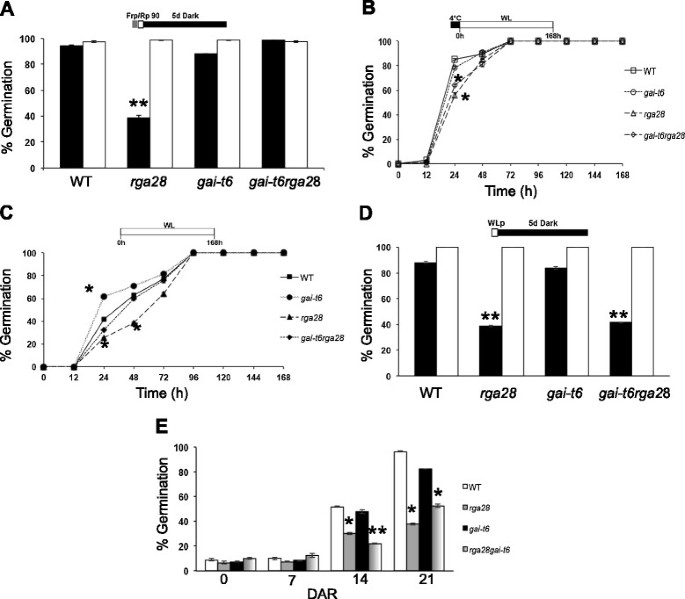

Under phyB-dependent conditions, in the absence of stratification, germination rate ofrga28mutant seeds (28 DAR) was only 38%, compared with almost 100% ofgai-t6andgai-t6rga28seeds and of wild-type seeds. Instead, after stratification, all mutant lines and wild-type seeds germinated completely (Figure1A).

rga28andgai-t6mutant seeds show different germination phenotypes.Germination rates of wild-type,rga28,gai-t6andgai-t6rga28mutant seeds. Seeds were germinated with or without stratification. 28 Days After Ripening (DAR) seeds germinated respectively: under phyB-dependent germination conditions(A), white light, with or without stratification(B, C)and in the dark(D). White bars/symbols refer to seeds germinated with stratification, black bars/symbols without stratification.(E)Germination of seeds after 0, 7, 14, 21 DAR in white light, without stratification. The diagram at top depicts the light treatment scheme for the experiments. FRp, Far Red pulse; Rp, Red pulse of 90 μmol m−2s−1; WLp, White Light pulse. Error bars = SEM. P values were obtained from a Student’s unpaired two-tailttest comparing the mutant with its control (* = p ≤ 0,05 ** = p ≤ 0,01).

Under white light the only substantial difference in the germination rate of stratified seeds was observed at 24 hours betweenrga28andgai-t6rga28mutant seeds compared to wild-type ones (56%, 64% and 85% respectively), and in all cases 100% germination was attained in 72 hours (Figure1B). In the absence of cold treatment, although all lines reached 100% germination after 96 hours,gai-t6seeds germinated faster andrga28seeds slower than wild-type, whilegai-t6rga28mutants showed the same germination kinetics of the latter, i.e. roughly 60%, 40% and 30%, respectively, after 24 hours (Figure1C). After 5 days in the dark, stratified seeds of all mutant lines germinated completely as did wild-type seeds; on the contrary, without stratification, the germination rate ofgai-t6and wild-type seeds were similar (above 80%), whereas bothrga28andgai-t6rga28seeds germinated significantly less (approximately 40%) (Figure1D). As one function of stratification is to remove seed dormancy, we verified whether therga28germination phenotype was due to increased seed dormancy.

A seed germination assay, without stratification, was performed with freshly harvested mutant seeds, and with seeds respectively at 7, 14, 21 DAR, to asses a possible loss of dormancy due to seed storage. The germination rate was scored after seven days under white light. Freshly harvested and 7 DAR singlegai-t6andrga28and doublegai-t6rga28mutant seeds showed a germination rate lower than 10%, similarly to wild-type seeds (8% germination). The germination ofgai-t6and wild-type seeds increased up to 48% and 52%, respectively, after two weeks of storage; dormancy was almost completely relieved after three weeks - 83% and 97% germination forgai-t6and wild-type seeds, respectively. Conversely,rga28andgai-t6rga2814 DAR seeds still retained a significantly higher level of dormancy, as revealed by a germination rate of 30% and 22%, respectively. After three weeks of storage bothrga28andgai-t6rga28mutant seeds lost part of their dormancy (38% and 53% germination, respectively), although onlyrga28seeds showed a significant difference with wild-type seeds (97% germination) (Figure1E).

这些结果指向不同的影响GAIandRGA在种子休眠:RGA的缺失严重增加eases dormancy, while lack of GAI partially compensatesRGAinactivation, asgai-t6rga28mutant seeds show a milder phenotye than therga28single mutant.

Thedag1andrga28mutations are not epistatic

To elucidate the genetic relationship between the DOF geneDAG1and the DELLA–encoding genesRGAandGAI, we constructed thedag1rga28double mutant. In contrast, attempts to isolate thedag1gai-t6double mutant were unsuccessful (see below). As thedag1andrga28mutant lines are in different ecotypes (Ws-4 and Col-0, respectively), several lines for each genotype - double mutants, parental lines and wild-type - were selected and analysed in order to minimize the effect of the ecotype on the phenotype of interest.

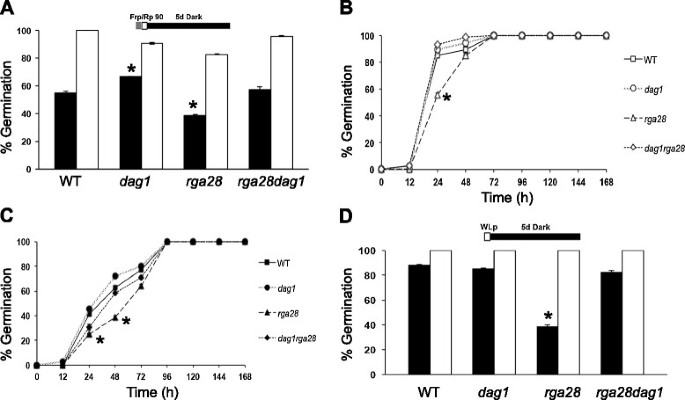

Seed germination assays under phyB-dependent conditions (i.e. after exposure to a pulse of R light) revealed that, in the absence of stratification, the germination rate ofdag1rga28double mutant seeds was similar to wild-type seeds (58% and 56% respectively), whereas thedag1andrga28single mutant seeds had significant different germination rates (68% and 39% respectively), compared to wild-type. In contrast, upon stratification all mutant lines and wild-type seeds germinated almost completely (Figure2A). After stratification and under white light, 100% germination was attained in 72 hours by mutant and wild-type seeds, althoughrga28mutant seeds showed a significative slower kinetics (56% at 24 hours, compared to 85, 89 and 91%, respectively, of wild-type,dag1anddag1rga28) (Figure2B). Under white light without stratification,rga28seeds exhibit germination properties significantly lower (25%) thandag1rga28(31%), wild-type (41%) anddag1(45%) seeds as measured at 24 hours (Figure2C). After 5 days in the dark, stratified seeds of the mutant lines germinated completely as wild-type seeds (Figure2D); on the contrary, in the absence of stratification, wild-type,dag1anddag1rga28double mutant seeds showed similarly high germination rates (88%, 85% and 83%, respectively), whereasrga28种子发芽表现出显著降低percentage (39%) (Figure2D).

Thedag1andrga28mutations are not epistatic.Germination rates of wild-type,rga28,dag1anddag1rga28mutant seeds, grown 7 days: under phyB-dependent germination conditions(A), in white light, with or without stratification(B, C)and in the dark.(D). White bars/symbols refer to seeds germinated with stratification, black bars/symbols without stratification. The diagram at top depicts the light treatment scheme for the experiments. FRp, Far Red pulse; Rp, Red pulse of 90 μmol m−2s−1; WLp, White Light pulse. Error bars = SEM. P values were obtained from a Student’s unpaired two-tailttest comparing the mutant with its control (* = p ≤ 0,05 ** = p ≤ 0,01).

Since thedag1rga28seed germination phenotype is not completely similar to that of the single mutants,dag1andrga28do not have an epistatic relationship.

Simultaneous inactivation of bothDAG1andGAIaffects embryo development

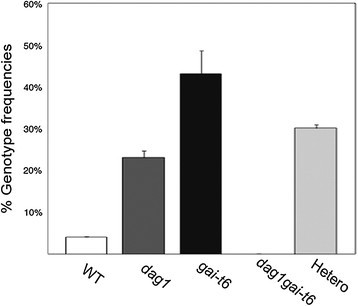

As for thedag1gai-t6double mutant, we analysed by PCR-based genotyping more than one hundred F2 plants derived from both thedag1×gai-t6and the reciprocal cross, but we were unable to isolate thedag1gai-t6double mutant. To verify the possibility that concurrent inactivation of bothDAG1andGAImay affect embryo development, we performed a macroscopic analysis of siliques from plants of the F1 generation, which contain F2 seeds segregating different combinations of wild-type and mutant alleles of bothDAG1andGAI(Figure3A). We compared the F2 seeds derived from the crosses with those ofdag1andgai-t6single mutant seeds and of their respective wild-type seeds. Moreover, as the single mutants are in different ecotypes, the F2 seeds were also compared with seeds in siliques derived from a Ws-4 × Col-0 cross, and with the parental lines (dag1,gai-t6) also derived from thedag1×gai-t6cross (Additional file1: Figure S1). The results of this analysis revealed a high percentage of aborted seeds (35%) in the F2 generation from thedag1 × gai-t6and reciprocal crosses, compared with about 1% in the different wild-type siliques, including those from the Ws-4 × Col-0 cross. Interestingly, while we observed only 2% of aborted seeds in the siliques of thegai-t6single mutant, siliques from thedag1single mutant contained 17% of abnormal seeds, indicating that lack of DAG1 results in embryonic defects and that the simultaneous absence of GAI enhances this phenotype (Figure3A,B). In addition, in order to minimize the possibility that the embryo-lethal phenotype could be due to the combination ofdag1with thegai-t6allele in the Col-0 ecotype, we performed the same crosses with thegai-t6allele in Ler background. Analysis by PCR-based genotyping of about one hundred F2 plants was again unsuccessful, as we could not isolate thedag1gai-t6double mutant. Both the frequencies of thedag1andgai-t6single mutants and of the heterozygous lines were different from what expected (Figure4). Further genetic analyses will be required to verify whether any of the different allelic combinations has viability and/or germination problems.

DAG1 and GAI are essential for embryo development. (A)Siliques from F1 plants derived from thedag1xgai-t6cross, with developing seeds and embryos, compared with siliques ofdag1, Ws,gai-t6, Col-0, anddag1gai-t6 DAG1-HA. The image is a bright-field photograph of the silique showing developing seeds under 10× magnifications.(B)Frequencies of defective embryos in the following genetic backgrounds:gai-t6, Col-0,dag1, Ws-4, F1,dag1gai-t6 DAG1-HA. F1 is referred to embryos/seeds of F1 plants derived from the crossdag1×gai-t6. Bars represent the average of about one hundred mature siliques, error bars represents SD. P values were obtained from a Student’s unpaired two-tailttest comparing the mutant with its control (* = p ≤ 0,05 ** = p ≤ 0,01).

Thedag1×gai-t6(Ler) cross gives embryo-lethal double mutants.Genotype frequencies of the F2 plants derived from thedag1(Ws-4) xgai-t6(Ler) cross obtained by PCR-based genotyping. About 100 F2 plants were subjected to PCR-based genotyping for the following alleles:DAG1,dag1,GAIandgai-t6. Hetero is referred to plants that resulted heterozygotes forDAG1orGAIor both.

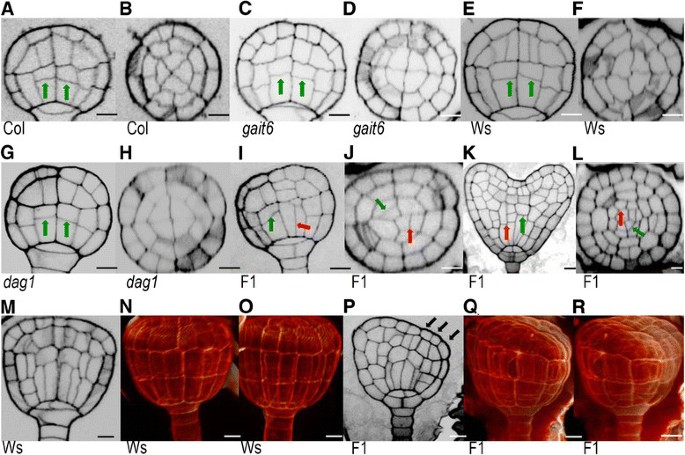

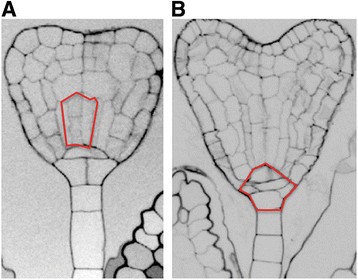

We then analyzed the phenotype of F2 embryos and checked for additional phenotypes compared to wild-type and single mutants. In wild-type,dag1andgai-t6single mutants, transversal division of basal vascular cells at globular stage led to asymmetric cells (Figure5A,C,E,G). In contrast, some F2 embryos displayed longitudinal divisions (Figure5I,K), thus altering the radial symmetry of the embryo axis (Figure5J,L) observed in control plants (Figure5B,D,F,H). An additional phenotype was observed at the transition stage where individuals of the F2 embryos showed aberrant triangular shape, as highlighted by the arrow (Figure5P) and also shown in the 3D image (Figure5Q,R) compared to wild-type embryos (Figure5M-O). Interestingly, a small percentage ofdag1embryos also showed similar phenotypes (Figure6).

Embryo phenotype ofdag1,gai-t6and of F1 plants derived from thedag1x gai-t6cross. (A-J)Transversal and longitudinal section of wild-type (Ws-4 and Col-0)(A, B, E, F),gai-t6(C, D),dag1(G, H), and F1 embryos at globular stage(I, J).(K, L)Transversal and longitudinal section of F2 embryos at heart stage.(M-R)Longitudinal and 3D vizualisation of wild-type(M-O)and F1 embryos at transition stage(P-R). F1 is referred to embryos from F1 plants derived from the crossdag1×gai-t6. Green arrows indicate correct division plane. Red arrows indicate incorrect division plane. Black arrows indicate sagging of the embryo. Scale bar 10 μm.

Expression ofDAG1complements embryo defects and germination properties

To verify whether expression of the DAG1-HA chimaeric protein would, at least in part, complement the above-described embryo defects, we crossed thedag1DAG1-HAline with thegai-t6single mutant. Out of 28 F2 plants derived from the cross, we were able to isolate sevendag1gai-t6DAG1-HAlines. Macroscopic analysis of siliques from these plants revealed normally-developing seeds with a percentage of aborted seeds similar to wild-type (Figure3A,B). Moreover, we analysed the germination properties ofdag1gai-t6DAG1-HAseeds, as well as ofdag1DAG1-HAseeds, under phyB-dependent germination conditions, and in the presence or absence of stratification both under white light and in the dark (Figure7). The transgenic lines were compared with the corresponding wild-type (Ws and Ws/Col respectively fordag1DAG1-HAanddag1gai-t6DAG1-HA). Under all conditions tested, the germination rates of these transgenic lines were not significantly different from those of wild-type seeds. The only conspicuous difference regardeddag1DAG1-HAseeds which germinated significantly slower than wild-type (Figure7B,C).

Overexpression ofDAG1-HAcomplements the embryo mutant phenotype.Germination assays ofdag1DAG1-HAanddag1gai-t6DAG1-HAseeds (28 DAR) and wild-type (Ws/Col-0), under phyB-dependent germination conditions(A), in white light(B, C)and in the dark.(D, E)with(B, D)or without stratification(C, E). Error bars = SEM. P values were obtained from a Student’s unpaired two-tailttest comparing the mutant with its control (* = p ≤ 0,05 ** = p ≤ 0,01).

DAG1is expressed during embryo development

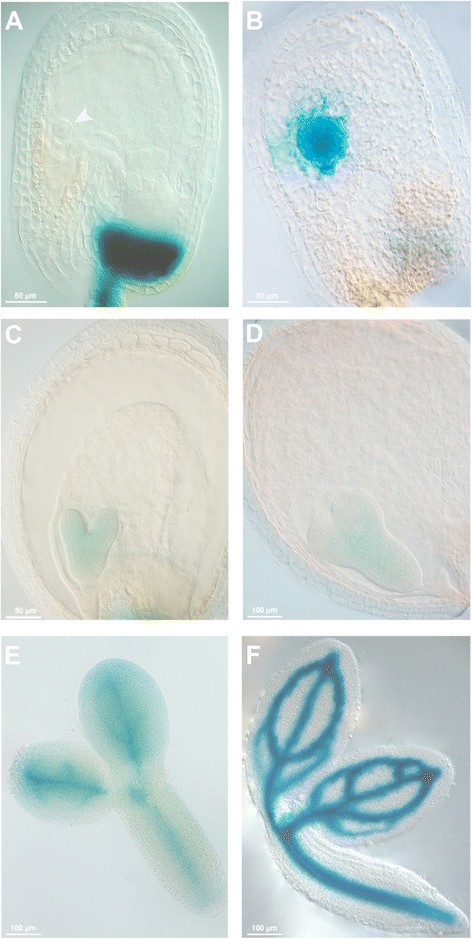

We have previously shown thatDAG1expression is localized in the vascular system of the plant. TheDAG1promoter is also active in the vascular tissue of seeds during the process of imbibition [21],[22]. The involvement of DAG1 in the process of embryogenesis prompted us to further analyseDAG1expression during embryo development. We used aDAG1:GUSreporter transgenic line utilized in a previous study [21]. GUS activity was observed in embryos at the globular, heart, torpedo, and bent cotyledon stages. Interestingly, GUS staining was extended to all cells at the globular stage, whereas from the heart stage on it was restricted to the procambium (Figure8).

Discussion

We had previously characterized the DAG1 transcription factor as a repressor of seed germination [19]–[21] that acts downstream of PIL5 and negatively regulates GA biosynthesis [22]. As also the DELLA proteins RGA and GAI act downstream of PIL5 in seed germination [7], we investigated on the respective roles of these DELLA proteins in this process and their relationship with DAG1.

RGA and GAI have distinct roles in seed germination

RGA and GAI have been reported to be involved in several growth processes [16],[17]; however, the single null mutantsrga24, rga28andgai-t6were reported to lack any visible phenotype, and a functional redundancy of the two proteins had been suggested [8],[13],[16]. As for seed germination, the singlerga28andgai-t6mutants were shown to behave similarly to the wild-type in response to increasing red light fluences [7].

Here we show that therga28andgai-t6single mutants have different seed germination phenotypes, suggesting (at least partially) distinct functions for RGA and GAI in this developmental process. In particular,rga28seeds have, in the absence of stratification, a lower germination rate than wild-type irrespective of light conditions. This germination phenotype is likely due to an increased dormancy - as revealed by our germination assays on freshly harvested seeds and on seeds at different DAR.

Our data suggest that RGA plays a negative role in the regulation of seed dormancy. RGA has been shown to be involved in seed dormancy and to be directly activated by SPATULA (SPT), which also inhibits the negative regulator of RGA MOTHER OF-FT-AND-TFL1 (MFT) [24]-[26], but dormancy of therga28single mutant was not analysed by those authors.

On the other hand, our work shows that although thegai-t6single mutant does not have a dormancy phenotype, lack of GAI partially compensatesRGAinactivation, asgai-t6rga28mutant seeds show a milder phenotye than therga28single mutant. In addition, in our handsgai-t6突变体种子发芽显示潜在的轻微ly higher than wild-type under white light in the absence of stratification, similar to that of thedag1mutant ([19]; this work).

It should be pointed out thatRGAandGAIalso differ in their transcriptional regulation in connection with DAG1: while we have recently shown a reciprocal negative transcriptional control of the genesDAG1andGAIduring seed germination [23], a previous microarray analysis of ours showed thatGAI, but notRGA, was upregulated byDAG1inactivation [27].

Inactivation ofGAIenhances thedag1embryo mutant phenotype

We have previously reported thatdag1siliques contain numerous aborted seeds [19]. In this work, attempts to isolate thedag1gai-t6double mutant were unsuccessful, suggesting that the simultaneous inactivation of bothDAG1andGAIresults in an embryo-lethal phenotype, i.e. a more severe phenotype than inactivation of onlyDAG1. This is not due to an additive effect of the two mutations, since a statistical analysis of the siliques revealed that whiledag1contained 17% abnormal seeds, only 2% aborted seeds were present ingai-t6and in wild-type siliques. Thus, the absence of GAI does not in itself lead to seed abnormalities, but inactivation of this gene in adag1mutant background is apparently responsible for embryo lethality. This may be an additional indication of the cooperation between DAG1 and GAI in controlling common target genes that we pointed out in a previous paper, where we showed that the two proteins cooperate in negatively regulating theAtGA3ox1gene [23]. Consistently, we could restore embryo development by expressing the DAG1-HA chimaeric protein in thedag1gai-t6double mutant background.

The earliest phenotype of thedag1gai-t6double mutant is an impairment in cell divisions in the basal portion of the globular stage embryo, the hypophyseal and the procambial precursor cells, but not in the ground precursor cells. Consistent with this mutant phenotype, theDAG1promoter is active in the embryo starting from the globular stage.

Simultaneous inactivation ofPOLTERGEIST(POL) andPOLTERGEIST-LIKE 1(PLL1)的结果在基底胚胎模式的缺陷ning similar to what described here for thedag1gai-t6double mutant [28]. POL and PLL1 are two related phosphatases required to establish the vascular axis in the embryo, by inducing expression of the WUSCHEL (WUS) homologWUSCHEL RELATED HOMEOBOX 5(WOX5).

It is tempting to speculate that DAG1 and GAI may also function in this molecular network. As the double mutantdag1gai-t6has a more severe phenotype than the double mutantpolpll1,有人可能会假设DAG1和丐帮upstre行动am of POL and PLL1. Further analysis on the functional and molecular relationship among these factors will help unveiling the complex signaling underlying embryo development.

Conclusions

Here we show that the DELLA proteins RGA and GAI have, at least partially, different roles in the seed germination process. Indeed,RGAinactivation results in increased seed dormancy, whereas lack of GAI partially compensates this phenotype, asgai-t6rga28mutant seeds show a milder phenotye than therga28single mutant.

With respect to DAG1, our data suggest that this latter and RGA act in independent branches of the PIL5-controlled germination pathway, whereas GAI and DAG1 are involved in embryo development since thedag1gai-t6double mutant proved embryo-lethal. This latter finding should be regarded in the context of the cooperation of DAG1 and GAI in regulating common target genes, such as in the case of the GA biosynthetic geneAtGA3ox1that we have very recently demonstrated [23].

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

dag1is the allele described in Papiet al.[19] in Ws-4 ecotype. Therga28,gai-t6andgai-t6rga28(Col-0) mutants, kindly provided by Dr. G. Choi, are described by Ohet al.[7].dag1rga28was obtained by crossing the single mutants, and identified in the F3 generation by PCR analysis. Thegai-t6anddag1mutants were crossed using both lines as female parent. F1 plants derived from the cross were analysed by PCR to confirm the presence of the mutant alleles in heterozygosis. As the single mutants were in different ecotypes, the parental lines (dag1,rga28, gai-t6) and the wild-type were also selected from the cross. Several lines for each genotype were selected and analysed in order to minimize the effect of the two different ecotypes on the phenotypes of interest. Therga24andgai-t6mutant lines in Ler ecotype [14] were from the ABRC stock.

Thedag1gai-t6DAG1-HAlines were isolated from the F2 generation derived from the crossgai-t6×dag1DAG1-HA,by PCR-based genotyping.

AllArabidopsis thalianalines used in this work were grown in a growth chamber at 24/21% C with 16/8-h day/night cycles and light intensity of 300 μmol/m-2 s−1as previously described [19],[22]. All the primers used for the screenings are listed in Additional file2: Table S1.

Seed germination assays

All seeds used for germination tests were harvested from mature plants grown at the same time, in the same conditions, and stored for the same time (7, 14, 21, 28 DAR) under the same conditions, except where freshly harvested seeds were used. Germination assays were performed according to Gabrieleet al. [22]. For phyB-dependent germination experiments, seeds, with or without cold treatment (stratification, 2 days at 4°C), were exposed to a pulse of FR light (40 μmol m−2s−1), then a pulse of R light (90 μmol m−2s−1) and subsequently kept in the dark for 5 days: under these conditions germination is mediated only by phyB. For the germination assays in the dark, seeds were exposed to a pulse of white light, then kept in the dark for 5 days. All germination assays were repeated with three seed batches, and one representative experiment is shown. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of three biological repeats (25 seeds per biological repeat). P values were obtained from a Student’s unpaired two-tailttest comparing the mutant with its control (* = p ≤ 0,05 ** = p ≤ 0,01).

Cytology and microscopy

For staining of ovules and seeds, siliques were harvested and slit open on one side. Tissue was fixed in 50% methanol/10% acetic acid and then subjected to 3 h treatment of 1% SDS and 0.2 N NaOH at room temperature. Siliques were rinsed in water, incubated in 25% bleach solution (2.5% active Cl−) for 1 to 5 min, rinsed again, and then transferred to 1% periodic acid. The samples were then further processed as described before [29].

For confocal microscopy, a LSM 710 (Zeiss) spectral confocal laser-scanning microscope was used. Excitation wavelengths for propidium iodide-stained samples was 488 nm. Data were processed for some two-dimensional orthogonal sections, 3D rendering, using the open source software Osirix ([30];http://www.osirix-viewer.com/AboutOsiriX.html) on a quadxeon 2.66-Ghz, 2-GB RAM Apple Mac pro workstation.

Analysis of defective embryos of the F1 plants derived from the crossdag1×gai-t6. was performed under an Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Zeiss). Bars represent the average of about one hundred mature siliques, error bars represents SD. P values were obtained from a Student’s unpaired two-tailttest comparing the mutant with its control (* = p ≤ 0,05 ** = p ≤ 0,01).

GUS constructs and analysis

TheDAG1:GUSline is the one described in Gualbertiet al.[21]. Histochemical staining and microscopic analysis were carried out according to Blazquezet al.[31]. Stained embryos (after washing in 70% ethanol) were analysed and photographed under an Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Zeiss).

Additional files

References

- 1.

Koornneef M, Karssen CM: Seed Dormancy and Germination in Arabidopsis. Cold Spring Harbor, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 1994.

- 2.

Koornneef M, Bentsink L, Hilhorst H: Seed dormancy and germination. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5: 33-36. 10.1016/S1369-5266(01)00219-9.

- 3.

Shinomura T, Nagatani A, Chory J, Furuya M: The induction of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana is regulated principally by phytochrome B and secondarily by phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 1994, 104: 363-371.

- 4.

Yamaguchi S, Smith MW, Brown RGS, Kamiya Y, Sun TP: Phytochrome regulation and differential expression of gibberellin 3β-hydroxylase genes in germinating Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell. 1998, 10: 2115-2126.

- 5.

Seo M, Hanada A, Kuwahara A, Endo A, Okamoto M, Yamauchi Y, North H, Marion-Poll A, Sun TP, Koshiba T, Koshiba T, Kamiya Y, Yamaguchi S, Nambara E: Regulation of hormone metabolism in Arabidopsis seeds: phytochrome regulation of abscisic acid metabolism and abscisic acid regulation of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J. 2006, 48: 354-366. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02881.x.

- 6.

Oh E, Kim J, Park E, Kim JI, Kang C, Choi G: PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting basic helix–loop–helix protein, is a key negative regulator of seed germination inArabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2004, 16: 3045-3058. 10.1105/tpc.104.025163.

- 7.

Lee HS, Sun TP, Kamiya Y, Choi G: PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH protein, regulates gibberellin responsiveness by binding directly to the GAI and RGA promoters in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell. 2007, 19: 1192-1208. 10.1105/tpc.107.050153.

- 8.

Tyler L, Thomas SG, Hu J, Dill A, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Sun TP: DELLA proteins and gibberellin-regulated seed germination and floral development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135: 1008-1019. 10.1104/pp.104.039578.

- 9.

Fleet CM, Sun TP: A DELLAcate balance: the role of gibberellin in plant morphogenesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005, 8: 77-85. 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.11.015.

- 10.

Sun TP: The molecular mechanism and evolution of the GA-GID1-DELLA signaling module in plants. Curr Biol. 2011, 21: 338-345. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.036.

- 11.

Feng S, Martinez C, Gusmaroli G, Wang Y, Zhou J, Wang F, Chen L, Yu L, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Kircher S, Schäfer E, Fu X, Fan LM, Deng XW: Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature. 2008, 451: 475-479. 10.1038/nature06448.

- 12.

Ariizumi T, Hauvermale A, Nelson SK, Hanada A, Yamaguchi S, Steber CM: Lifting DELLA Repression of Arabidopsis Seed Germination by Nonproteolytic Gibberellin Signaling. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162: 2125-2139. 10.1104/pp.113.219451.

- 13.

Peng J, Carol P, Richards DE, King KE, Cowling RJ, Murphy GP, Harberd NP: The ArabidopsisGAIgene defines a signalling pathway that negatively regulates gibberellin responses. Genes Dev. 1997, 116: 3194-3205. 10.1101/gad.11.23.3194.

- 14.

Silverstone AL, Mak PY, Martínez EC, Sun TP: The newRGAlocus encodes a negative regulator of gibberellin response inArabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1997, 146: 1087-1099.

- 15.

Silverstone AL, Ciampaglio CN, Sun TP: The Arabidopsis RGA gene encodes a transcriptional regulator repressing the gibberellin signal transduction pathway. Plant Cell. 1998, 10 (2): 155-169. 10.1105/tpc.10.2.155.

- 16.

Dill A, Sun TP: Synergistic derepression of gibberellin signaling by removing RGA and GAI function inArabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2001, 159: 777-785.

- 17.

King K, Moritz T, Harberd N: Gibberellins are not required for normal stem growth in Arabidopsis thaliana in the absence of GAI and RGA. Genetics. 2001, 1596: 767-776.

- 18.

Cao D, Hussain A, Cheng H, Peng J: Loss of function of four DELLA genes leads to light- and gibberellin-independent seed germination in Arabidopsis. Planta. 2005, 2236: 105-113. 10.1007/s00425-005-0057-3.

- 19.

Papi M, Sabatini S, Bouchez D, Camilleri C, Costantino P, Vittorioso P: Identification and disruption of an Arabidopsis zinc finger gene controlling seed germination. Genes Dev. 2000, 14: 28-33.

- 20.

Papi M, Sabatini S, Altamura MM, Henning L, Schafer E, Costantino P, Vittorioso P: Inactivation of the phloem-specific DOF zinc finger gene DAG1 affects response to light and integrity of the testa of Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128: 411-417. 10.1104/pp.010488.

- 21.

Gualberti G, Papi M, Bellucci L, Ricci I, Bouchez D, Camilleri C, Costantino P, Vittorioso P: Mutations in the DOF zinc finger genes DAG1 and DAG2 influence with opposite effects the germination of Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell. 2002, 14: 1253-1263. 10.1105/tpc.010491.

- 22.

Gabriele S, Rizza A, Martone J, Circelli P, Costantino P, Vittorioso P: The DOF protein DAG1 mediates PIL5 activity on seed germination by negatively regulating the GA biosynthetic geneAtGA3ox1. Plant J. 2010, 61: 312-323. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04055.x.

- 23.

Boccaccini A, Santopolo S, Capauto D, Lorrai R, Minutello E, Serino G, Costantino P, Vittorioso P: The DOF protein DAG1 and the DELLA protein GAI cooperate in negatively regulatingAtGA3ox1gene.Molecular plant2014, in press.,

- 24.

Penfield S, Josse EM, Kannangara R, Gilday AD, Halliday KJ, Graham IA: Cold and light control seed germination through the bHLH transcription factor SPATULA. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15: 1998-2006. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.010.

- 25.

Penfield S, Gilday AD, Halliday KJ, Graham IA: DELLA-mediated cotyledon expansion breaks coat-imposed seed dormancy. Curr Biol. 2006, 16 (23): 2366-2370. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.057.

- 26.

Vaistij FE, Gan Y, Penfield S, Gilday AD, Dave A, He Z, Josse EM, Choi G, Halliday KJ, Graham IA: Differential control of seed primary dormancy in Arabidopsis ecotypes by the transcription factor SPATULA Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013, 110: 10866-10871.

- 27.

Rizza A, Boccaccini A, Lopez-Vidriero I, Costantino P, Vittorioso P: Inactivation of the ELIP1 and ELIP2 genes affects Arabidopsis seed germination. New Phytol. 2011, 190: 896-905. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03637.x.

- 28.

Song S-K, Hofhuis H, Min Lee M, Clark SE: Key divisions in the early Arabidopsis embryo require POL and PLL1 phosphatases to establish the root stem cell organizer and vascular axis. Develop. Cell. 2008, 15: 98-109. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.008.

- 29.

Truernit E,鲍比H, Dubreucq B, Grandjean O, Runions J, Barthélémy J, Palauqui JC: High-resolution whole-mount imaging of three-dimensional tissue organization and gene expression enables the study of Phloem development and structure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008, 20: 1494-1503. 10.1105/tpc.107.056069.

- 30.

Rosset A, Spadola L, Ratib O: OsiriX: an open-source software for navigating in multidimensional DICOM images. J Digit Imaging. 2004, 17: 205-216. 10.1007/s10278-004-1014-6.

- 31.

Blázquez MA, Soowal LN, Lee I, Weigel D: LEAFY expression and flower initiation inArabidopsis. Development. 1997, 124: 3835-3844.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Choi who kindly provided therga28,gai-t6,gai-t6rga28突变体线。这项工作是部分支持research grants from Ministero dell’Istruzione, Università e Ricerca, Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale, and from Sapienza Università di Roma to PC, and from Istituto Pasteur Fondazione Cenci Bolognetti to PV.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PV designed the research. AB and SS contributed to the experimental design and to analysis of the results. AB, SS, DC, RL and EM performed the experiments. KB and JCP performed microscopic analyses of thegai-t6dag1double mutant embryos. All authors analyzed and discussed the data. AB and SS prepared the figures and PV wrote the article. PC supervised the research and the writing of the manuscript. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Figure S1.

Additional file 1: Analysis of defective embryos in the hybrid wild-type, F1,dag1,gai-t6lines (Ws-4/Col-0). Bars represent the average of about one hundred mature siliques, error bars represents SD. P values were obtained from a Student’s unpaired two-tailttest comparing the mutant with its control (* = p ≤ 0,05 ** = p ≤ 0,01). (PDF 690 KB)

Table S1.

Additional file 2: List of the primers used for the screenings of the double mutants, and the isolation of thedag1gai-t6DAG1-HAtransgenic line. (PDF 34 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open AccessThis article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visithttps://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Boccaccini, A., Santopolo, S., Capauto, D.et al.Independent and interactive effects of DOF affecting germination 1 (DAG1) and the Della proteins GA insensitive (GAI) and Repressor ofga1-3(RGA) in embryo development and seed germination.BMC Plant Biol14,200 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-014-0200-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Keywords

- DAG1

- GAI

- RGA

- Seed germination

- Embryogenesis

- Arabidopsis thaliana