- Research article

- Open Access

- 发表:

Genome-Wide analysis of the AAAP gene family in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis)

BMC Plant Biologyvolume17, Article number:29(2017)

Abstract

Background

Members of the amino acid/auxin permease (AAAP) gene family play indispensable roles in various plant metabolism and biosynthesis processes. Comprehensive analysis of AAAP genes has been conducted in Arabidopsis, rice, maize and poplar, but has not been reported from moso bamboo. Phylogenetics, evolutionary patterns and further expression profiles analysis of the AAAP gene family in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) will increase our understanding of this important gene family.

Results

In this current study, we conducted phylogenetic, gene structure, promoter region, divergence time, expression patterns and qRT-PCR analysis of the 55 predicted AAAP genes in moso bamboo based on the availability of the moso bamboo genome sequence. We identified 55 putative AAAP (PeAAAP1-55) genes, which were divided into eight distinct subfamilies based on comparative phylogenetic analysis using 184 full-length protein sequences, including 55 sequences from moso bamboo, 58 sequences from rice and 71 sequences from maize. Analysis of evolutionary patterns and divergence showed that the PeAAAP genes have undergone a extensive duplication event approximately 12 million years ago (MYA) and that the split between AAAP family genes in moso bamboo and rice occurred approximately 27 MYA. The microarray analysis suggested that some genes play considerable roles in moso bamboo growth and development. We investigated the expression levels of the 16 AAP subfamily genes under abiotic stress (drought, salt and cold) by qRT-PCR to explore the potential contributions to stress response of individualPeAAAPgenes in moso bamboo.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest thatPeAAAPgenes play crucial roles in moso bamboo growth and development, especially in response to abiotic stress conditions. Our comprehensive, systematic study of the AAAPs gene family in moso bamboo will facilitate further analysis of the functions and evolution ofAAAPgenes in plants.

Background

Amino acids are important organic substances that serve as an indispensable source of organic nitrogen for growth and development, playing vital roles in the metabolism, structure and biosynthesis of various compounds in eukaryotic organisms [1,2]。In plants, amino acids are important components of nucleotides, chlorophyll, phytohormones and secondary metabolites [2]。Amino acids are transported between different organs through both xylem and phloem, requiring the activity of amino acid transporters (AATs) in the plasma membrane [3]。The first plant amino acid transporter was found in Arabidopsis 23 years ago, namelyAtAAP1/NAT2[4,5]。Amino acid/auxin permease (AAAP) proteins are found in almost all eukaryotic organisms, belonging to the AAT family [1,6,7]。These proteins contribute to the responses to biotic and abiotic stresses and long distance amino acid transport, and they mediate the transport of amino acids across the cellular membrane [8–10]。此外,先前的报告显示,一些members of amino acid transporters were located within the tonoplast, which were devoted to transport amino acids between vacuole and cytoplasm, and regulated the storage of amino acids in vacuole [11–14]。

To date, the AAAP family is one of the largest families of AATs [1,6,7], comprising eight subfamilies, namely ProTs [15], GATs [16], LHTs [17], AAPs [1,18], ANTs [12] and ATL subfamilies (ATLa and ATLb) [19]。And allAAAP基因有一个特定的域,PF01490 (Aa_trans)。

To date, some functions of AAAP proteins have been studied in model plants such as Arabidopsis [20], poplar [21], maize [22] and rice [23]。AtAAP3appears to be involved in amino acid uptake from the phloem and soil [24]。A recent study showed thatAtAAP5plays a role in amino acid uptake by the root [1]。AtAAP6is expressed in roots, sink leaves, cauline leaves and xylem parenchyma, suggesting that it functions in amino acid uptake from the xylem [25]。In addition,AtAAP8might play a crucial role in amino acid transport during fruit development [1,26]。In rice, 18 genes in the AAP subfamily have been identified [23], three of which (OsAAP1,OsAAP7andOsAAP16) encode general AAAP proteins, whereasOsAAP3does not [27]。OsAAP3transports the basic amino acids lysine and arginine and has distinct substrate specificity compared with other rice orArabidopsisAAPs [27]。OsAAP6is contribute to enhance root absorption and affect the distribution of various amino acids in early stages of seed development [28]。

Bamboo, one of the most important non-timber forest products worldwide, comprises over 70 genera and 1,200 species [29]。A majority of these species are distributed in the subtropical regions of China, especially regions south of the Yangtze River. Moso bamboo is an important species in China with the highest value in several areas among all bamboos, being used to produce timber, paper, artwork and food (young shoots) [30]。However, moso bamboo faces many types of environmental conditions during growth and development, such as high or low temperatures, salt concentrations and soil moisture levels, which limit its distribution and quality. A previous study showed that functional and regulatory proteins contribute to abiotic stress resistance in plant [31], and AAAP proteins are the fundamental functional proteins. Therefore, in the current study, we investigated AAAP proteins in moso bamboo to identify proteins that function in stress resistance. To date, bioinformatic analysis in model plants has greatly increased our understanding ofAAAPgenes. In addition, the draft genome sequence of moso bamboo was completed in 2013 [29], providing a great bioinformatics foundation to perform a comprehensive genome survey of the AAAP family in moso bamboo.

Methods

Identification of moso bamboo AAAP genes

The conserved AAAP domains (PF01490) of rice AAAP protein sequences were originally applied as seed sequences to search the NCGR database (www.ncgr.ac.cn/bamboo) [29]。Redundant sequences were removed manually based on the results of Cluster W 2.11 alignment [32], and each candidate sequence was confirmed using the Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/) [33,34] and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) databases [35]。The number of amino acids, CDS lengths and physicochemical parameters ofAAAPgenes were obtained from Bamboo GDB (http://www.bamboogdb.org). Comparing coding sequence and the corresponding genomic DNA sequences ofAAAPgenes, we obtained their exon/intron structures from GSDS. The TMHMM Server version 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) was used to predict the putative TM (transmembrane) regions of each PeAAAP protein with default settings.

Phylogenetic and conserved motif analyses

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalX 2.11 software [36], and a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the alignment with the N-J method using MEGA 6.0 software and bootstrap analysis of 1,000 replicates. The combined phylogenetic tree of OsAAAP, ZmAAAP and PeAAAP proteins was generated using the same method. The motifs of PeAAAP proteins were identified using the MEME tool (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) (parameter setting: maximum number of motifs, 20; maximum width, 50.).

Calculation of Ka/Ks values

Pairwise alignment ofAAAPgenes encoding sequences of the orthologous and paralogous pairs was first performed using ClustalX 2.11 software and the results of alignment were subsequently further analyzed using the MEGA 6.0, and then the synonymous substitution rate (Ks) and nonsynonymous substitution rate (Ka) were computed using DnaSP 5 software [37,38]。The divergence time (T) was calculated using the formula T = Ks/2λ (λ = 6.5 × 10−9) [29,39]。The following parameters were used to perform sliding window analysis of the Ka/Ks ratios of all homologous gene pairs: window size, 150 bp; step size, 9 bp.

Putative promoter region analysis

The 2,000-bp upstream sequences of the genetic sequences were identified as putative promoter regions, which contains variouscis-regulatory elements identified using the PLACE website (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/) [40]。

Plant material and growth conditions

Eight-week-old seedlings were grown in artificial growth chamber with a constant photoperiod (14 h light/8 h darkness) and temperatures average around 22 °C. Moso bamboo seeds for breeding seedlings were collected in the Tianmu Mountain National Nature Reserve in Zhejiang Province, China. In addition, the permission of seeds collection for the experiments was obtained from Prof. Dingqing Tang of School of Forestry and Bio-technology, Zhejiang A & F University. And the identification of these seeds was also performed by Prof. Dingqing Tang. The seedlings were treated with 20% PEG-6000, 200 mM NaCl and 4 °C to induce drought stress, salt stress and cold stress, respectively. In order to obtain reliable experimental data and reduce experimental error, for each sample, we executed three repeated trials for the same stimulation and carried out three biological replicates for expression analysis. For each induction treatment, we collected samples at six time points (0, 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h) and immediately stored at – 80 °C freezer for RNA extraction. In addition, untreated plant materials (0 h) were used as the control group.

Expression profile analysis

To study gene expression levels ofPeAAAPgenes in different tissues or development stages. The expression profile for each gene was obtained from Short Read Archive (SRA) database of NCBI. And then the raw RNA-seq reads of BioProject ERP001341 were trimmed to remove low quality base-calls (Q < 20) and adaptor sequences with pipeline Fastq clean [41]。The paired clean reads were mapped to thePhyllostachys heterocyclareference genome using pipeline tophat2 with defaults parameters, and different expressed genes were detected by Cufflinks [42]。The heatmap ofPeAAAPgenes in seven different tissues and/or developmental stages (leaf, early panicle, advanced panicle, root, rhizome, 20-cm shoot and 50-cm shoot) was exhibited using the Heatmapper Plus tool [43]。

qRT-PCR analysis

To research the expression levels ofPeAAAP基因,存在分析基于SYBR-green fluorescence was performed for each members of the AAP subfamily. Total RNA was extracted from the plant samples using RNA prep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, which was reverse transcribed into cDNA subsequently using a PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa). Primer Express 3.0 was used to design the gene-specific primers of eachPeAAPgenes, and the tonoplast intrinsic protein 41 (TIP41) was used as an internal control [44]。The following program was used for qRT-PCR: 95 °C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 55 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 10 s.

Results

Identification of AAAP genes in moso bamboo

The AAAP candidate sequences from the moso bamboo genome were verified using the Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/) [33,34] and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) databases [35]。Fifty-five potential AAAP sequences were ultimately identified as AAAP genes, which were designatedPeAAAP01toPeAAAP55.Detailed information about the 55 AAAP genes was obtained using the moso bamboo GDB server (http://www.bamboogdb.org), including the predicted lengths of CDSs, sizes of encoded proteins and physicochemical parameters; this information is shown in Table1. The lengths of the CDSs range from 252 bp to 2,166 bp, with an average size of 1,281 bp. The identified AAAP genes in moso bamboo with an average size of 426 aa, which peak on 721 aa and have a minimum value at 83 aa. The predicted molecular weights of the 55PeAAAPgene products range from 9.28 kDa (PeAAAP3) to 77.56 kDa (PeAAAP10), with a mean value of 46.48 kDa. The predicted PIs for the 55PeAAAPgene products are below 11.0, with most values approximately 8.0 or 9.0. However, the PI of one gene product (PeAAAP29) is below 5.0, whereas one is greater than 10.0 (PeAAAP37).

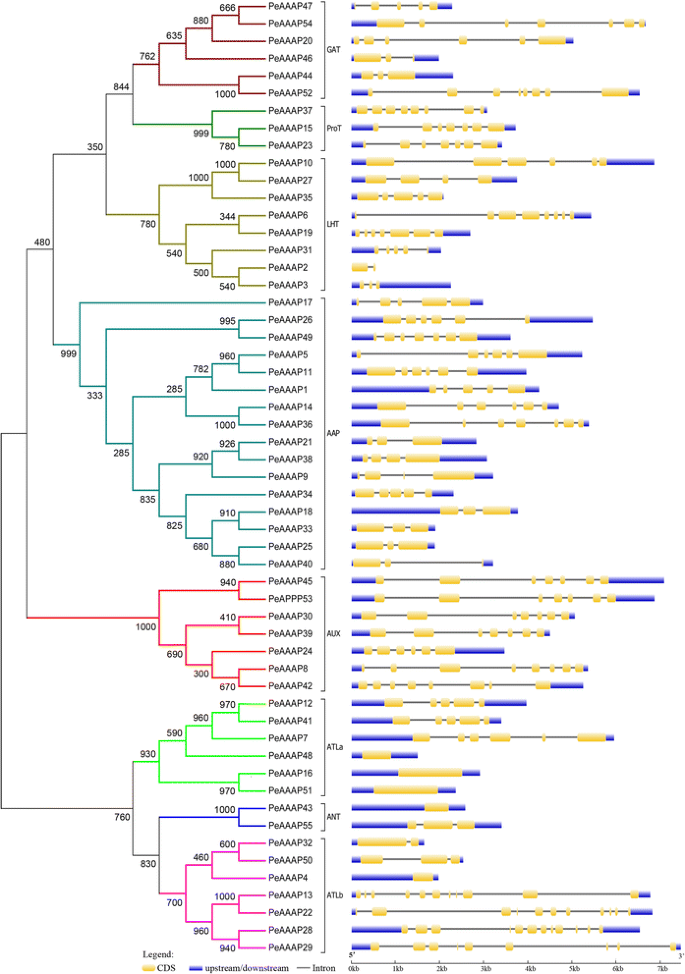

The GSDS online tool was used to determine the exons/introns structure of each predictedPeAAAPgene (Fig.1). These results show that fivePeAAAPgenes (PeAAAP4,PeAAAP16,PeAAAP43,PeAAAP48andPeAAAP51) exclude introns, while the remaining genes contain 1–11 introns, andPeAAAP2is no upstream and downstream (Fig.1). The TMHMM Server v2.0 was used to predict the putative TM regions ofPeAAAPgenes, which numbers in most genes ranged from 8 to 13 (Additional file1: Figure S1). Interestingly, we found that genes of the same subfamily have similar numbers of TMs, especially all members of AUXs contain 10 TMs. In AAP subfamily, the numbers of TMs was less than or equal to 10. However, a previous report, showing thatAtAAP1had 11 TMs [45]。

Phylogenetic relationship and gene structures of AAAP proteins in moso bamboo.Left: Phylogenetic tree of PeAAAPs constructed by neighbor-joining method based on the results of sequence alignment. Bootstrap values from 1000 replicates were indicated at each node. The proteins on the tree can be divided into eight distinct subfamilies and the branches of different subfamilies were marked by different colors. There was a special noted that subfamilies ATL were further divided into two groups (ATLa and ATLb).Right: Exons, introns and untranslated regions (UTRs) were indicated by yellow rectangles, gray lines and blue rectangles, respectively

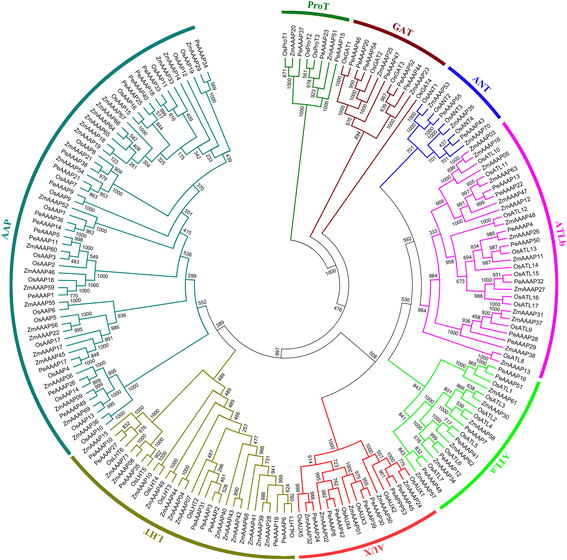

Phylogenetic and conserved domain analysis of AAAP proteins in moso bamboo

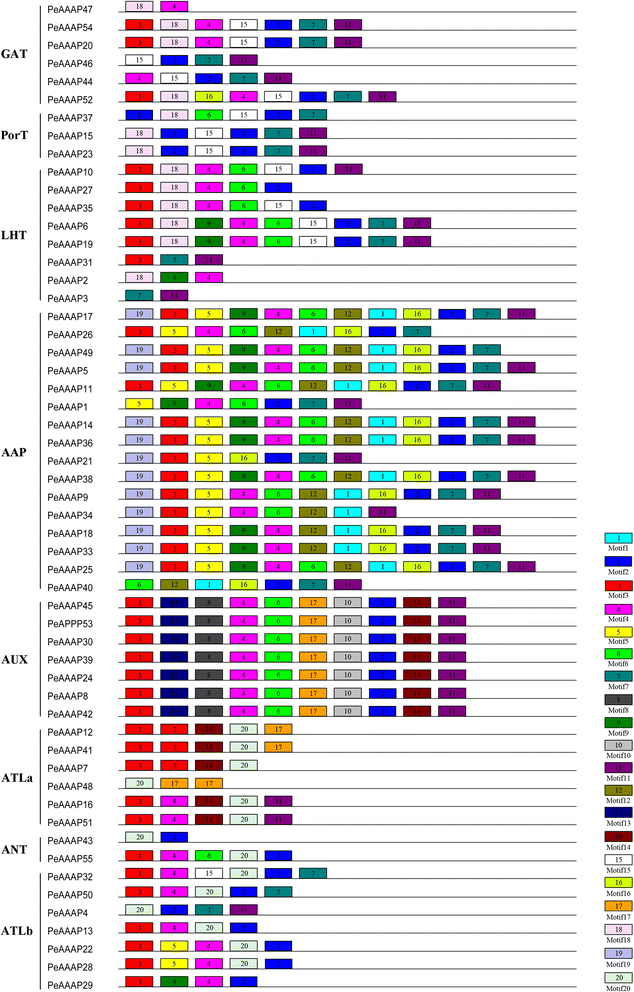

The phylogengtics tree was constructed based on the alignment of full-length amino acid sequences to evaluate the evolutionary relationship among these members of AAAP family. The genes were divided into eight distinct subfamilies, and the AAP subfamily is the largest one of all. To further examine the diversification of thePeAAAPgenes, 20 distinct motifs (Fig.2) were found using MEME web server (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme). Detailed information about the 20 putative motifs included names, widths and best possible matches were listed in Additional file2: Table S1. The functions of each motif were identified by searching Pfam and SMART database, showing that nine motifs (1 - 6, 9, 10 and 15) encode Aa-trans domains, while the remaining 11 motifs do not encode any domain. Interestingly, some motifs were specific to only one or two subfamilies. For example, motifs 8, 10 and 13 are exclusively found in the AUX subfamily, and motif 1 is only present in the AAP subfamily. Motifs 2 and 4 are found in all of the subfamilies except the ATLa and PorT subfamily, respectively. All members of the AUX subfamily have similar numbers of motifs (Fig.2), indicating that the structures of members are highly conserved in the same subfamily.

Schematic representation of the 20 conserved motifs in PeAAAP proteins. Conserved motifs of the PeAAAP proteins were identified using the online MEME program based on 55 full length amino acid sequences. Each specific motif was marked by different colored box, and their names in the center of the boxes. The length of each box in the figure didn’t represent the actual motif size

进化模式和潜水rgence of the AAAP gene family in moso bamboo, rice and maize

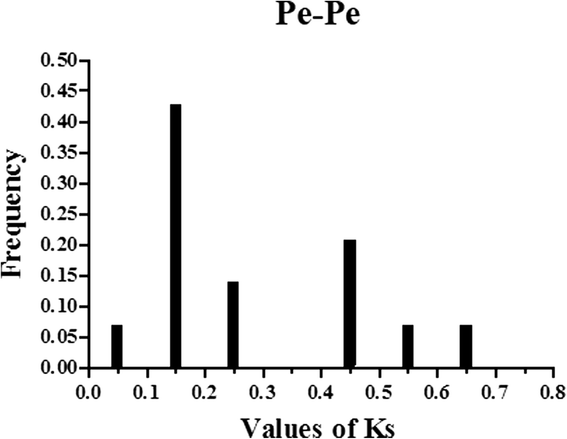

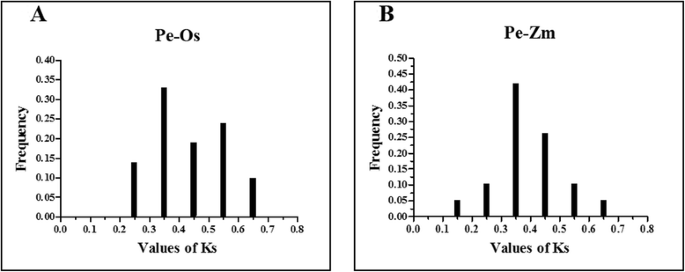

我们确定了14个假字(Pe-Pe)毛竹bamboo genome and 21 orthologs (Pe-Os) between moso bamboo and rice, and 19 orthologs (Pe-Zm) between moso bamboo and maize, using phylogeny-based and bidirectional best-hit methods. The formula T = Ks/2λ was used to evaluate the divergence times between moso bamboo, maize and rice, and relative Ks values were used as a proxy for time. All of the paralogous and orthologous pairs are listed in Table2. The distribution of Ks values of paralogous pairs (Pe-Pe) peaked at approximately 0.15, as shown in Fig.3. This result suggests that AAAP genes in moso bamboo have undergone a large-scale duplication event approximately 12 million years ago (MYA). The Ks values distribution of orthologous genes (Pe-Os and Pe-Zm) is shown in Fig.4aand Fig.4b, respectively. Interestingly, both Pe-Os and Pe-Zm had the same peak at approximately 0.35, showing that these genes have diverged approximately 27 MYA. A previous study showed that bamboo underwent whole-genome duplication 7–12 MYA, while rice and moso bamboo, as well as maize and moso bamboo, diverged 48.6 and 64.6 MYA, respectively [29]。It indicated that the AAAP family has undergone gene evolution after its separation from rice and maize. In general, Ka/Ks ratio less than 1, equal to 1 and greater than 1 means negative or stabilizing selection, neutral selection and positive selection, respectively [46,47]。To investigate the trend of Ka/Ks ratio in the coding sequences of each gene pairs, we performed sliding-window analysis of Pe-Pe (Additional file3: Figure S2),Pe-Os (Additional file4: Figure S3) and Pe-Zm (Additional file5: Figure S4) gene segments, indicating that the AAAP domains have undergone strong purifying selection (Ka/Ks < < 1) during the process of evolution.

Putative promoter region analysis

Cis-elements play critical roles in plant growth and development, including determining the tissue-specific or stress-responsive expression patterns of genes, and multi-stimulus-responsive genes are closely correlated withcis-regulatory elements in their promoter regions [48,49]。Cis-elements have decisive effects on binding to target genes. In this study, we identified three typecis-elements, including cold-responsive, drought-responsive and salt-responsive elements in the promoter regions to help elucidate the potential functions ofAAAPgenes in moso bamboo [50,51]。Numerouscis-elements were widespread in the promoter regions, such as S000176 and S000415 for drought stress, S000453 for salt stress and S000407 for cold stress (Additional file6: Table S2). Moreover, contrasting with thecis-regulatory elements of salt stress, there was the higher amount ofcis-elements for drought and cold stress. These results suggest that transcription factors that regulateAAPgenes may respond to abiotic stress and have the potential for improving abiotic stress responses, especially drought and cold. These findings may be helpful for further investigating stress tolerance mechanisms in moso bamboo.

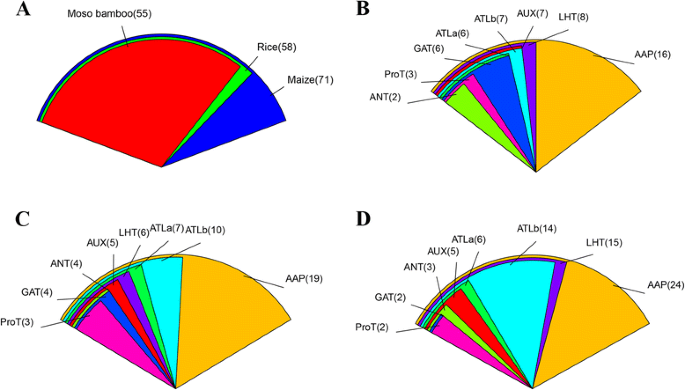

Comparative analysis of AAAP genes in moso bamboo, rice and maize

To date, most studies have focused on analyzing the AAAP family in rice and maize. To further analyze the evolutionary relationships betweenAAAP基因在毛竹竹,水稻和玉米,我们构造ed an N-J phylogenetic tree (Fig.5) of AAAPs using ClustalX 2.11 based on 184 full-length AAAP protein sequences, including 55 sequences from moso bamboo, 58 from rice and 71 from maize. The detailed characteristics of the AAAP genes from rice and maize are listed in Additional file7: Table S3. The phylogenetic tree clearly shows that the 184 AAAP proteins could be divided into eight distinct groups. A count of the number of AAAP proteins in every moso bamboo (Fig.6b), rice (Fig.6c) and maize (Fig.6d)亚科。结果是consistent with the previous reports that AAP subfamily is the largest one in AAAP family among these three species. We also found that moso bamboo contains fewerAAAPgenes than rice and maize (Fig.6a), suggesting that thePeAAAPgenes have undergone a gene loss event after divergence from the last common ancestor of moso bamboo, rice and maize.

Comparison of AAAP proteins from moso bamboo, rice and maize.a: Comparison of AAAP proteins from moso bamboo, rice and maize; different color represents different species, and numbers of AAAP proteins in each species were marked.b,canddshowed that distribution and comparison of each subfamily for moso bamboo, rice and maize, respectively; different subfamilies were represented with different colors, and numbers of members in each subfamily were marked

Differential expression profiling of moso bamboo AAAP genes

In general, the overall analysis of gene expression profiles in different tissues will contribute to study the dynamic gene expression ofAAAPgenes in moso bamboo. The high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), as one of essential next generation sequencing technology, will allow to reveal a snapshot of RNA presence and quantity from a genome at a given moment in time [52,53]。In addition, the draft genome sequence of moso bamboo has been released [29]。By now, many studies of expression profiles in several gene families were reported and mainly focused on different tissues [54–56]。While, the genome-wide expression profile ofPeAAAPgenes still remains unclear.

We performed a microarray analysis to determine the expression level of eachAAAPgenes on different tissues in moso bamboo based on the above advantages. Finally, the heatmap was produced (Fig.7) based on the microarray data of 55 moso bambooAAAP(Additional file8: Table S4) genes downloaded from the NCBI. From the microarray results, it was apparent that a fewAAAPgenes exhibited tissue-specific expression patterns. For instance, two genes (PeAAAP1andPeAAAP5) andPeAAAP34were highly expressed in advanced panicle and leaves, respectively. While the rest members ofPeAAAPgenes showed express at least two tissues. Above all, there are twenty-one genes (PeAAAP7, PeAAAP10, PeAAAP13, PeAAAP14, PeAAAP15, PeAAAP16, PeAAAP17, PeAAAP27, PeAAAP28, PeAAAP29, PeAAAP36, PeAAAP41, PeAAAP43, PeAAAP45, PeAAAP50, PeAAAP51 and PeAAAP53) that were widely expressed in all these seven tissues or developmental stages, implying their essential roles in the process of moso bamboo growth and development.

Expression profiles of moso bamboo AAAP genes across different tissues and development stages. Heatmap showing hierarchical clustering of 55PeAAAPgenes across different tissues analyzed. Color scale erected vertically at the right side of the picture represents log10 expression values, green represents low level and red indicates high level of transcript abundances. L, leaf; P1, early panicle; P2, advanced panicle; R, root; Rh, rhizome; S1, 20-cm shoot; S2, 50-cm shoot. Every member of AAP subfamily was marked by red stars

Six gene pairs (PeAAAP12/PeAAAP41, PeAAAP14/PeAAAP36, PeAAAP21/PeAAAP38, PeAAAP26/PeAAAP49, PeAAAP43/PeAAAP55 and PeAAAP44/PeAAAP52) of these above identified exhibit distinct expression patterns in different tissues or developmental stages, suggesting that duplicated genes may have different evolutionary fates. For instance,PeAAAP43is expressed at a high level in rhizome and shoots, however, its counterpartPeAAAP55shows slight relative expression level. By contrast, remaining gene pairs have the same or similar patterns of expression accumulation.

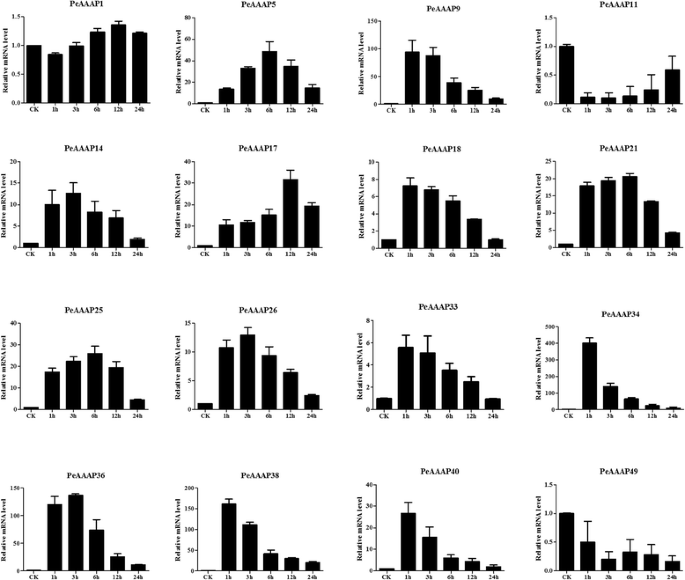

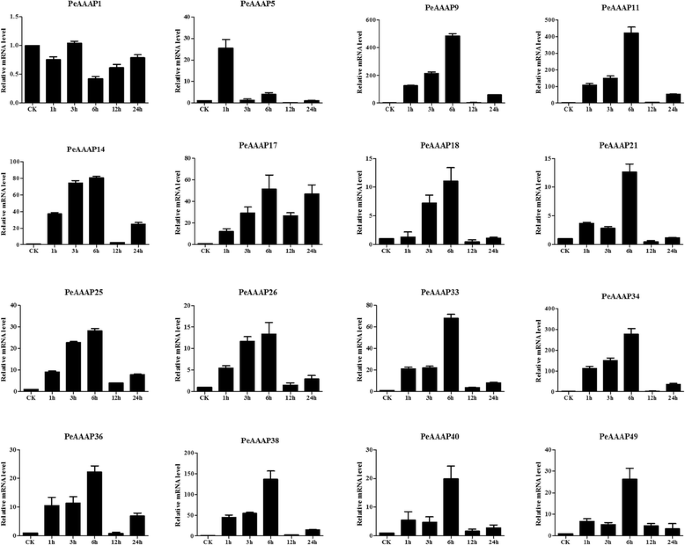

qRT-PCR analysis of moso bamboo AAAP genes

The phylogenetic analysis indicated that the AAP subfamily contains 16PeAAAPgenes and that these genes are closely related to stress-responsive genes in rice. This observation prompted us to investigate possible stress-responsive genes among the 16PeAAAPgenes by qRT-PCR. We investigated the expression levels of 16 selected AAP subfamily members (PeAAAP1,PeAAAP5,PeAAAP9,PeAAAP11,PeAAAP14,PeAAAP17,PeAAAP18,PeAAAP21,PeAAAP25,PeAAAP26,PeAAAP33,PeAAAP34,PeAAAP36,PeAAAP38,PeAAAP40andPeAAAP49) in the leaves of young seedlings in response to PEG, salt and cold treatment using qRT-PCR. The specific primers used in qRT-PCR analysis of these genes are shown in Additional file9: Table S5.

For the PEG (drought) treatment (Fig.8), 10 of the 16 genes (PeAAAP5,PeAAAP9,PeAAAP11,PeAAAP14,PeAAAP18,PeAAAP21,PeAAAP25,PeAAAP26,PeAAAP33, PeAAAP36,PeAAAP38andPeAAAP40) were distinctly upregulated in response to PEG (drought) treatment. Four genes (PeAAAP9,PeAAAP14,PeAAAP26andPeAAAP36) were the most highly expressed during early (1 h) treatment, followed by a decrease in expression during subsequent treatment (Fig.8). The expression of two genes (PeAAAP18andPeAAAP25) peaked at 24 h.PeAAAP11,PeAAAP21,PeAAAP38andPeAAAP40were upregulated under 3 h PEG (drought) stress treatment and downregulated at later time points, especiallyPeAAAP11, with an expression level over 150-fold higher at 3 h than at 0 h. By contrast, three genes (PeAAAP17,PeAAAP34andPeAAAP40) were downregulated under PEG (drought) stress treatment (Fig.8). In addition, there are three genes (PeAAAP1,PeAAAP5andPeAAAP33) were specific, showing slight (<4-fold that at 0 h) changes of expression level in response to PEG (drought) treatment.

Two genes in the AAP subfamily (PeAAAP11andPeAAAP49) were downregulated by cold stress, whereas 13 other genes of this subfamily (PeAAAP5,PeAAAP9,PeAAAP14,PeAAAP17,PeAAAP18,PeAAAP21,PeAAAP25,PeAAAP26,PeAAAP33,PeAAAP34,PeAAAP36,PeAAAP38andPeAAAP40) were clearly upregulated by this treatment. Six genes (PeAAAP9,PeAAAP18,PeAAAP33,PeAAAP34,PeAAAP38andPeAAAP40) were the most highly expressed during early (1 h) treatment, and their expression gradually decreased at all later time points (Fig.9). Moreover, these genes were dramatically upregulated at the 1 h time point, especiallyPeAAAP9,PeAAAP34andPeAAAP38(more than 150-fold that of control levels; Fig.9). The expression ofPeAAAP1changed only slightly over the 24-h time course. Three genes (PeAAAP5, PeAAAP21andPeAAAP25) exhibited similar trends in expression, with a gradual increase in expression during the early time points, a peak at 6 h and a significant, gradual decrease at all later time points. The expression ofPeAAAP14,PeAAAP26andPeAAAP36peaked at 3 h, while the expression level ofPeAAAP17was highest at 12 h (Fig.9).

All 16 genes in the AAP subfamily (PeAAAP1,PeAAAP5,PeAAAP9,PeAAAP11,PeAAAP14,PeAAAP17,PeAAAP18,PeAAAP21,PeAAAP25,PeAAAP26,PeAAAP33,PeAAAP34,PeAAAP36,PeAAAP38,PeAAAP40andPeAAAP49) were upregulated under NaCl (salt) stress treatment except forPeAAAP1(Fig.10). Only one gene (PeAAAP5) showed the highest expression level at 1 h, whereas the 14 other genes (PeAAAP9,PeAAAP11,PeAAAP14,PeAAAP17,PeAAAP18,PeAAAP21,PeAAAP25,PeAAAP26,PeAAAP33,PeAAAP34,PeAAAP36,PeAAAP38,PeAAAP40andPeAAAP49) exhibited similar expression patterns, with gradual increases in expression at the early time points and significant, gradual decreases at all later time points; the expression of all 14 genes peaked at 6 h (Fig.10).

In summary, the qRT-PCR results revel that 13 genes(PeAAAP9,PeAAAP11,PeAAAP14,PeAAAP17,PeAAAP18,PeAAAP21,PeAAAP25,PeAAAP26,PeAAAP34, PeAAAP36,PeAAAP38,PeAAAP40,andPeAAAP49) exhibited significant changes in response to all three stress treatments, showing that these genes may exhibit different responses to abiotic stress. It was not difficult to found that these results accord with the putative promoter analysis results of AAP subfamily members (Additional file6: Table S2). There were severalcis-elements showing a widely distribution in these members, such as elements S000415 (ACGT), S000407 (CANNTG) and S000453 (GAAAAA) in drought, cold and salt stress response, respectively. These results suggested that a number ofPeAAAPgenes might play crucial roles in regulating abiotic stress responses.

Discussion

As an indispensable gene family, the eukaryotic-specific AAAP family plays a pivotal role in the process of plant growth and development, which is one of the largest families of AATs identified to date [21,22]。According to previous studies, severalAAAPgenes have been characterized both physiologically and genetically, such as Arabidopsis AAP and AUX subfamily [18,25,57,58], and rice AAP subfamily [27,28]。By contrast, AAAP family members have not previously been characterized in moso bamboo. Therefore, in the current study, we identified and characterized 55 predictedAAAPgenes in moso bamboo using genome wide analysis, and compared these with 58OsAAAPsand 71ZmAAAPs, showing that the number of AAAP genes in moso bamboo (55) is the fewest among these three species [22,23]。The 184 AAAP proteins were found to be divided into eight distinct subfamilies, with every subfamily containing different members from these three species, meaning that AAAP genes had diversified before moso bamboo, rice and maize split. A count of these subfamilies in different species shows that AAP subfamily is the largest one. AndAAAPgenes with the similar structure showed a tendency to be grouped into the same subfamily, we sought some more valuable evidence to support the reliability of the subfamily classification, including gene structure, motif compositions and TM regions. Furthermore, all members in AUX subfamily have the same numbers and types of TM regions, exon/intron structures and motif compositions, suggesting that these members share a closer evolutionary relationship in the process of AAAP evolution. These results are in accordance with the results of a previous study of the AAAP family in poplar [21]。Furthermore, these results may show that the functions diversified among different members ofAAAPgenes in mso bamboo. In addition, a previous study showed thatAAP1had 11 TMs in Arabidopsis, which was different from AAP subfamily in moso bamboo, signifying the divergence between different species.

Recent gene duplication events, which help organisms adapt to different environments during growth and development [59,60] as well as are an important evolutionary mechanism for the rapid expansion and evolution of gene families [46]。To better explain the patterns of macroevolution in moso bamboo, we calculated the value of Ks and Ka in moso bamboo, maize and rice. Specifically, we estimated the Ks and Ka models of paralogous genes (Pe-Pe) and orthologous genes (Pe-Os and Pe-Zm) and calculated the Ks value for each gene pair. We estimated that a large-scale duplication event was occurred approximately 12 MYA in moso bamboo and that the divergence times for orthologous genes (Pe-Os and Pe-Zm) was approximately 27 MYA. Penget al.estimated that the divergence time between moso bamboo and rice was 48.6 MYA, and maize was 64.6 MYA [29]。Ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks) can be used to measure the history of selection acting on coding sequences [61]。In general, Ka/Ks ratio less than 1, equal to 1 and greater than 1 means negative or stabilizing selection, neutral selection and positive selection, respectively [46,47]。Interestingly, in this study, the Ka/Ks ratios were less than 1, evidencing that the homologous gene pairs of AAAP family in moso bamboo have undergone a markedly purifying selection in the course of evolution.

The overall analysis of gene expression profiles in different tissues will contribute to study the dynamic gene expression ofAAAPgenes in moso bamboo. Therefore, we displayed the gene expression profiles of 55 identifiedPeAAAPgenes using published transcriptome data in NCBI database. Among them, twenty-one genes (PeAAAP7, PeAAAP10, PeAAAP13, PeAAAP14, PeAAAP15, PeAAAP16, PeAAAP17, PeAAAP27, PeAAAP28, PeAAAP29, PeAAAP36, PeAAAP41, PeAAAP43, PeAAAP45, PeAAAP50, PeAAAP51andPeAAAP53) exhibited relatively high expression level in all seven different tissues or developmental stages, suggesting their importance in the processes of moso bamboo growth and development. While a few numbers ofAAAPgenes show tissue-specific in this analysis.

In plant, many stress-related genes generated a series of stress responses to meet the adverse environmental condition during growth and development. AAAPs are highly regulated by environmental signals and play positive roles in abiotic stress responses in many plants [62,63]。AAPgenes were previously studied in several species, leading to the identification of 18 and 8 genes in the AAP subfamily in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively. The expression pattern of a gene can provide significant clues about its function, as demonstrated by Zhaoet al.[64]。Thus, we performed qRT-PCR to investigate the expression patterns ofPeAAAP基因波形的r PEG, cold and NaCl treatment. The PeAAP subfamily members showed significantly differential expression patterns under the three abiotic stresses examined. MostPeAAP基因被三个非生物压力调节treatments, suggesting thatPeAAPgenes may play crucial roles in abiotic stress responses in moso bamboo. For instance,PeAAAP9was highly expressed (over 100-fold that of control levels) under PEG (drought), cold and salt stress treatment. However, this gene shows a relatively lower expression frequency in leaf, meaning thatPeAAAP9responds to environmental stress. And conversely, some genes are unresponsive, especiallyPeAAAP1has low expression level in both microarray and qRT-PCR analysis. Furthermore, there were six paralogous pairs in AAP subfamily. Of these gene pairs, five of them (PeAAAP14/PeAAAP36,PeAAAP18/PeAAAP33,PeAAAP21/PeAAAP38,PeAAAP25/PeAAAP40andPeAAAP26/PeAAAP49) under cold treatment and two gene pairs (PeAAAP14/PeAAAP36andPeAAAP18/PeAAAP33) under salt treatment (NaCl) had similar expression levels and tendency in the same paralogous pair. These results might suggest that homologous genes had similar putative functions in processes of organism growth and development.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated phylogenetic, gene structure, promoter region, divergence time, microarray analysis and qRT-PCR analysis of the 55 predicted AAAP genes in moso bamboo. The qRT-PCR was used to explore the expression patterns of 16 selected AAAP genes under three abiotic stresses: drought (20% PEG-6000), salt (200 mM NaCl) and cold (cultured at 4 °C). These results of this study increase our understanding of AAAP family members, including their possible contributions to abiotic stress responses and other putative functions in process of moso bamboo growth and development.

Abbreviations

- AAAP:

-

Amino acid/auxin permease

- AAP:

-

Amino acid permease

- AAT:

-

Amino acid transporter

- ANT:

-

Aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter

- ATL:

-

Amino acid transporter-like

- AUX:

-

Auxin transporter

- CDS:

-

Coding sequence

- GABA:

-

伽马氨基酸丁酸

- GAT:

-

GABA transporter

- GDB:

-

Genome database

- GSDS:

-

Gene structures display server

- LHT:

-

Lysine histidine transporter

- MYA:

-

Million years ago

- NCBI:

-

National center of biotechnology information

- NCGR:

-

National center for gene research

- N-J:

-

Neighbour-Joining

- PEG:

-

Polyethylene glycol

- ProT:

-

Proline transporter

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- SMART:

-

Simple modular architecture research tool

- SRA:

-

Short read archive

- TIP:

-

Tonoplast intrinsic protein

- TMHMM:

-

Transmembrane hidden markov model.

References

- 1.

费舍尔WN, Kwart M,无角的年代,Frommer世行。Substrate specificity and expression profile of amino acid transporters (AAPs) in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(27):16315–20.

- 2.

Tegeder M, Offler CE, Frommer WB, Patrick JW. Amino acid transporters are localized to transfer cells of developing pea seeds. Plant Physiol. 2000;122(2):319–26.

- 3.

Fischer WN, André B, Rentsch D, Krolkiewicz S, Tegeder M, Breitkreuz K, Frommer WB. Amino acid transport in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3(5):188–95.

- 4.

Frommer WB, Hummel S, Riesmeier JW. Expression cloning in yeast of a cDNA encoding a broad specificity amino acid permease fromArabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90(13):5944–48.

- 5.

Hsu LC, Chiou TJ, Chen L, Bush DR. Cloning a plant amino acid transporter by functional complementation of a yeast amino acid transport mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(16):7441–45.

- 6.

Clark JA, Amara SG. Amino acid neurotransmitter transporters: structure, function, and molecular diversity. Bioessays. 1993;15(5):323–32.

- 7.

Young GB, Jack DL, Smith DW, Saier Jr MH. The amino acid/auxin:proton symport permease family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1415(2):306–22.

- 8.

Tegeder M, Wang XD, Frommer WB, Offler CE, Patrick JW. Sucrose transport into developing seeds ofPisum sativum L. Plant J. 1999;18(2):151–61.

- 9.

Wipf D, Ludewig U, Tegeder M, Rentsch D, Koch W, Frommer WB. Conservation of amino acid transporters in fungi, plants and animals. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27(3):139–47.

- 10.

Tegeder M. Transporters for amino acids in plant cells: some functions and many unknowns. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15(3):315–21.

- 11.

Yang H, Krebs M, Stierhof YD, Ludewig U. Characterization of the putative amino acid transporter genes AtCAT2, 3 & 4: The tonoplast localized AtCAT2 regulates soluble leaf amino acids. J Plant Physiol. 2014;171(8):594–01.

- 12.

Chen L, Ortizlopez A, Jung A, Bush DR. ANT1, an aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;125(4):1813–20.

- 13.

Carter C, Pan S, Zouhar J, Avila EL, Girke T, Raikhel NV. The vegetative vacuole proteome ofArabidopsis thalianareveals predicted and unexpected proteins. Plant Cell. 2004;16(12):3285–303.

- 14.

Endler A, Meyer S, Schelbert S, Schneider T, Weschke W, Peters SW, Keller F, Baginsky S, Martinoia E, Schmidt UG. Identification of a vacuolar sucrose transporter in barley and Arabidopsis mesophyll cells by a tonoplast proteomic approach. Plant Physiol. 2006;141(1):196–207.

- 15.

Rentsch D, Boorer KJ, Frommer WB. Structure and Function of Plasma Membrane Amino Acid, Oligopeptide and Sucrose Transporters from Higher Plants. J Membr Biol. 1998;162(3):177–90.

- 16.

Mcintire SL, Reimer RJ, Schuske K, Edwards RH, Jorgensen EM. Identification and characterization of the vesicular GABA transporter. Nature. 1997;389(6653):870–76.

- 17.

Chen L, Bush DR. LHT1, a lysine-and histidine-specific amino acid transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1997;115(3):1127–34.

- 18.

Bennett MJ, Marchant A, Green HG, May ST, Ward SP, Millner PA, Walker AR, Schulz B, Feldmann KA. Arabidopsis AUX1 gene: a permease-like regulator of root gravitropism. Science. 1996;273(5277):948–50.

- 19.

Okumoto S, Pilot G. Amino Acid Export in Plants: A Missing Link in Nitrogen Cycling. Mol Plant. 2011;4(3):453–63.

- 20.

Foster J, Lee YH, Tegeder M. Distinct expression of members of the LHT amino acid transporter family in flowers indicates specific roles in plant reproduction. Sex Plant Reprod. 2008;21(2):143–52.

- 21.

Wu M, Wu S, Chen Z, Dong Q, Yan H, Xiang Y. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the amino acid transporter gene family in poplar. Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2015;11(4):83.

- 22.

Sheng L, Deng L, Yan H, Zhao Y, Dong Q, Li Q, Li X, Cheng B, Jiang H. A Genome-Wide Analysis of the AAAP Gene Family in Maize. J Proteomics Bioinform. 2014;7(1):023–33.

- 23.

Zhao H, Ma H, Li Y, Wang X, Zhao J. Genome-Wide Survey and Expression Analysis of Amino Acid Transporter Gene Family in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49210.

- 24.

Okumoto S, Koch W, Tegeder M, Fischer WN, Biehl A, Leister D, Stierhof YD, Frommer WB. Root phloem-specific expression of the plasma membrane amino acid proton co-transporter AAP3. J Exp Bot. 2004;55(406):2155–68.

- 25.

Okumoto S, Schmidt R, Tegeder M, Fischer WN, Rentsch D, Frommer WB, Koch W. High affinity amino acid transporters specifically expressed in xylem parenchyma and developing seeds of Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(47):45338–46.

- 26.

Schmidt R, Stransky H, Koch W. The amino acid permease AAP8 is important for early seed development inArabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2007;226(4):805–13.

- 27.

Taylor MR, Reinders A, Ward JM. Transport function of rice amino acid permeases (AAPs). Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(7):1355–63.

- 28.

Peng B, Kong H, Li Y, Wang L, Zhong M, Sun L, Gao G, Zhang Q, Luo L, Wang G. OsAAP6 functions as an important regulator of grain protein content and nutritional quality in rice. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4847.

- 29.

Peng Z, Lu Y, Li L, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Gao Z, Lu H, Hu T, Yao N, Liu K. The draft genome of the fast-growing non-timber forest species moso bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla). Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):456–61.

- 30.

Wu H, Lv H, Li L, Liu J, Mu S, Li X, Gao J. Genome-Wide Analysis of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factors Family and the Expression Patterns of DREB Genes in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126657.

- 31.

Lata C, Prasad M. Role of DREBs in regulation of abiotic stress responses in plants. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(14):4731–48.

- 32.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–80.

- 33.

Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Böckler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34 suppl 1:D247–51.

- 34.

Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz H-R, Ceric G, Forslund K, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36 suppl 1:D281–88.

- 35.

Letunic I, Copley RR, Schmidt S, Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, Schultz J, Ponting CP, Bork P. SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32 suppl 1:D142–44.

- 36.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4876–82.

- 37.

Rozas J. DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis Using DnaSP. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;537(537):337–50.

- 38.

Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–52.

- 39.

Zhang Y-J, Ma P-F, Li D-Z. High-throughput sequencing of six bamboo chloroplast genomes: phylogenetic implications for temperate woody bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae). PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20596.

- 40.

Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plantcis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):297–300.

- 41.

Zhang M, Sun H, Fei Z, Zhan F, Gong X, Gao S. Fastq_clean: An optimized pipeline to clean the Illumina sequencing data with quality control. In: Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2014 IEEE International Conference on: 2014. New York: IEEE; 2014. p. 44–8.

- 42.

Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):562–78.

- 43.

Toufighi K, Brady SM, Austin R, Ly E, Provart NJ. The Botany Array Resource: e-Northerns, Expression Angling, and promoter analyses. Plant J. 2005;43(1):153–63.

- 44.

Fan C, Ma J, Guo Q, Li X, Wang H, Lu M. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56573.

- 45.

Chang HC, Bush DR. Topology of NAT2, a prototypical example of a new family of amino acid transporters. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(48):30552–57.

- 46.

Cannon SB, Mitra A, Baumgarten A, Young ND, May G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families inArabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2004;4(1):1.

- 47.

Shiu S-H, Karlowski WM, Pan R, Tzeng Y-H, Mayer KF, Li W-H. Comparative analysis of the receptor-like kinase family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Cell. 2004;16(5):1220–34.

- 48.

Le DT, Nishiyama R, Watanabe Y, Vankova R, Tanaka M, Seki M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Tran L-SP. Identification and expression analysis of cytokinin metabolic genes in soybean under normal and drought conditions in relation to cytokinin levels. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42411.

- 49.

Walther D, Brunnemann R, Selbig J. The regulatory code for transcriptional response diversity and its relation to genome structural properties inA. thaliana. Plos Genet. 2007;3(2):e11.

- 50.

Fang Y, You J, Xie K, Xie W, Xiong L. Systematic sequence analysis and identification of tissue-specific or stress-responsive genes of NAC transcription factor family in rice. Mol Gen Genomics. 2008;280(6):547–63.

- 51.

吴J,彭Z,刘年代,他Y,程L,香港F,王J, Lu G. Genome-wide analysis of Aux/IAA gene family in Solanaceae species using tomato as a model. Mol Gen Genomics. 2012;287(4):295–311.

- 52.

Schuster SC. Next-generation sequencing transforms today’s biology. Nat Methods. 2008;5(1):16–8.

- 53.

Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(1):1–13.

- 54.

李陆彭Z, T, L,刘X, Z, T H,杨X, Qi F, Guan J, Weng Q. Genome-wide characterization of the biggest grass, bamboo, based on 10,608 putative full-length cDNA sequences. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10(1):1–13.

- 55.

Gao ZM, Li CL, Peng ZH. Generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags from a normalized cDNA library of young leaf from Ma bamboo (Dendrocalamus latiflorus Munro). Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(11):2045–57.

- 56.

Gao J, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Qi F, Li X, Mu S, Peng Z. Characterization of the Floral Transcriptome of Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) at Different Flowering Developmental Stages by Transcriptome Sequencing and RNA-Seq Analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98910.

- 57.

Sanders A, Collier R, Trethewy A, Gould G, Sieker R, Tegeder M. AAP1 regulates import of amino acids into developingArabidopsis embryos. Plant J. 2009;59(4):540–52.

- 58.

Marchant A, Kargul J, May ST, Muller P, Delbarre A, Perrot‐Rechenmann C, Bennett MJ. AUX1 regulates root gravitropism in Arabidopsis by facilitating auxin uptake within root apical tissues. EMBO J. 1999;18(8):2066–73.

- 59.

Bowers JE, Chapman BA, Rong J, Paterson AH. Unravelling angiosperm genome evolution by phylogenetic analysis of chromosomal duplication events. Nature. 2003;422(6930):433–38.

- 60.

Zhenglong G, Steinmetz LM, Xun G, Curt S, Davis RW, Wen-Hsiung L. Role of duplicate genes in genetic robustness against null mutations. Nature. 2003;421(6918):63–6.

- 61.

Wu M, Li Y, Chen D, Liu H, Zhu D, Xiang Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the IQD gene family in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Sci Rep. 2016;6:24520.

- 62.

Grallath S, Weimar T, Meyer A, Gumy C, Suter-Grotemeyer M, Neuhaus J-M, Rentsch D. The AtProT family. Compatible solute transporters with similar substrate specificity but differential expression patterns. Plant Physiol. 2005;137(1):117–26.

- 63.

Ueda A, Shi W, Sanmiya K, Shono M, Takabe T. Functional analysis of salt-inducible proline transporter of barley roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42(11):1282–89.

- 64.

Zhao X, Huang J, Yu H, Wang L, Xie W. Genomic survey, characterization and expression profile analysis of the peptide transporter family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10(1):92.

Acknowledgements

We thank the professors and colleagues of the Laboratory of Modern Biotechnology, Key Laboratory of Crop Biology of Anhui Province and National Engineering Laboratory of Crop Stress Resistance Breeding for their advising and help in this research. And thank Prof. Dingqing Tang, School of Forestry and Bio-technology, Zhejiang A & F University, for giving us the great help in seeds collection for this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31670672) and Special Fund for Forest Scientific Research in the Public Welfare (No. 201404601).

Availability of data and materials

RNA-seq data for expression profiles from this article were downloaded from NCBI database (accession numbers: ERP001341) (http://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/?study=ERP001341). The genome sequences of moso bamboo, rice and maize were obtained from moso bamboo GDB server (http://www.bamboogdb.org), Rice Genome Annotation Project database (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu) and Phytozome database (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov), respectively. Moso bambooAAAPgene IDs were listed in Table1. The IDs of rice and maizeAAAPgene were exhibited in Additional file7: Table S3.

Authors’ contributions

The authors listed in this article have done the necessary work in the process of writing the article, as shown below: HLL constructed the main frame of this article and wrote the manuscript, MW participated in the plot of this article and collected plant materials, DYZ had a hand in designing and actualizing experiments in this article and assisted to complete the writing of this paper, FP collated and analyzed the experimental data and revised the manuscript, YJW helped to write the manuscript and implemented the soft ware, YW helped to handle figures and tables. YX, as the correspondence author, provided financial support for the article and designed the way and frame of this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Prediction of the transmembrane regions of 55 PeAAAPs. The transmembrane regions of the 55PeAAAPswere predicted using the TMHMM Server v2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dkservicesTMHMM). (TIF 606 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

MEME motif sequences and lengths ofAAAPgene family proteins in moso bamboo. (DOC 38 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S2.

Sliding-window analysis of Pe-Pe. (TIF 92 kb)

Additional file 4: Figure S3.

Sliding-window analysis of Pe-Os. (TIF 130 kb)

Additional file 5: Figure S4.

Sliding-window analysis of Pe-Zm. (TIF 121 kb)

Additional file 6: Table S2.

Summary of abiotic-stress induciblecis-elements in the promoter regions of AAP subfamily genes in moso bamboo. The names of 16 AAP genes (PeAAAP1, -5, -9, -11, -14, -17, -18, -21, -25, -26, -33, -34, -36, 38, -40, -49) were represented byPe1, -5, -9, -11, -14, -17, -18, -21, -25, -26, -33, -34, -36, 38, -40, -49, respectively. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 7: Table S3.

Detailed information aboutAAAPgenes in rice and maize. CDS, coding sequence; bp, base pair; aa, amino acids; MW, molecular weight; pI, isoelectric point; Da, Dalton. (DOCX 23 kb)

Additional file 8: Table S4.

Microarray data of 55AAAPgenes in moso bamboo. These primary data was downloaded from NCBI, and then the relative expression level (log10 expression values) of 7 different issues or development stages was obtained after a series of manual processing. L, leaf; P1, early panicle; P2, advanced panicle; R, root; Rh, rhizome; S1, 20-cm shoot; S2, 50-cm shoot. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 9: Table S5.

Primers used for qRT-PCR of 16 selected genes. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Wu, M., Zhu, D.et al.Genome-Wide analysis of the AAAP gene family in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis).BMC Plant Biol17,29 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-017-0980-z

Received:

Accepted:

发表:

Keywords

- Moso bamboo

- Amino acid/auxin permease

- Phylogenetic analysis

- Conversed motif

- 表达模式

- qRT-PCR