- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Isolation and functional validation of theCmLOX08promoter associated with signalling molecule and abiotic stress responses in oriental melon,Cucumis melovar.makuwaMakino

BMC Plant Biologyvolume19, Article number:75(2019)

Abstract

Background

Lipoxygenases (LOXs) play significant roles in abiotic stress responses, and identification ofLOXgene promoter function can make an important contribution to elucidating resistance mechanisms. Here, we cloned theCmLOX08promoter of melon (Cucumis melo) and identified the main promoter regions regulating transcription in response to signalling molecules and abiotic stresses.

Results

The 2054-bp promoter region ofCmLOX08from melon leaves was cloned, and bioinformatic analysis revealed that it harbours numerouscis-regulatory elements associated with signalling molecules and abiotic stress. Five 5′-deletion fragments obtained from theCmLOX08promoter—2054 (LP1), 1639 (LP2), 1284 (LP3), 1047 (LP4), and 418 bp (LP5)—were fused with a GUS reporter gene and used for tobacco transient assays. Deletion analysis revealed that in response to abscisic acid, salicylic acid, and hydrogen peroxide, the GUS activity of LP1 was significantly higher than that of the mock-treated control and LP2, indicating that the − 2054- to − 1639-bp region positively regulates expression induced by these signalling molecules. However, no deletion fragment GUS activity was induced by methyl jasmonate. In response to salt, drought, and wounding treatments, LP1, LP2, and LP4 promoted significantly higher GUS expression compared with the control. Among all deletion fragments, LP4 showed the highest GUS expression, indicating that − 1047 to − 1 bp is the major region regulating promoter activity and that the − 1047 to − 418-bp region positively regulates expression induced by salt, drought, and wounding, whereas the − 1284 to − 1047-bp region is a negative regulatory segment. Interestingly, although the GUS activity of LP1 and LP2 was not affected by temperature changes, that of LP3 was significantly induced by heat, indicating that the − 1284- to − 1-bp region is a core sequence responding to heat and the − 2054- to − 1284-bp region negatively regulates expression induced by heat. Similarly, the − 1047- to − 1-bp region is the main sequence responding to cold, whereas the − 2054- to − 1047-bp region negatively regulates expression induced by cold.

Conclusions

We cloned theCmLOX08启动子,证明了这是一个信号molecule/stress-inducible promoter. Furthermore, we identified core and positive/negative regulatory regions responding to three signalling molecules and five abiotic stresses.

Background

Lipoxygenases (LOXs: EC 1.13.11.12) are a class of non-haem iron-containing dioxygenases. Plant LOXs have been classified as 9-LOX and 13-LOX, according to their different oxygen positions, and are involved in enzymatic reactions associated with the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) during transmutation to unsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxides [1]. Plant LOXs, which are encoded by multigene families, have been shown to play roles in the response to abiotic stresses [2,3,4]. Overexpression ofTomloxDin transgenic tomatoes clearly indicated that this gene is involved in endogenous jasmonic acid (JA) synthesis, and in turn regulates the expression of plant defence genes and resistance to high temperature [5,6]. Similarly, pepperCaLOX1has been shown to increase resistance to osmotic, drought, and high salinity stress [7]. Furthermore, the persimmonDkLOX3gene has been found to play positive roles in enhancing tolerance to salt and drought, and the stress-responsive expression of this gene in theDkLOX3-OX line ofArabidopsiswas shown to be higher than that in the wild type [8]. Overexpression and silencing of thejaponicariceOsLOX1gene has indicated that this gene is involved in resistance to wounding associated with JA biosynthesis [9].LOXgene expression has been shown to be regulated in response to different abiotic stresses such as heat, cold, and wounding, or different signalling molecules such as methyl jasmonate (MeJA), abscisic acid (ABA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and salicylic acid (SA) [10,11,12,13].

启动子是一种特定序列的DNA upstream of the protein-coding region of a gene that contains numerouscis-regulatory elements and initiates transcription [14]. To date, a number of signalling molecule/stress-inducible elements have been identified in promoter regions, examples of which include a salicylic acid-responsive element (TCA) identified in tobacco [15], ABRE, acis-acting element involved in ABA responsiveness, in wheat and rice [16,17], and ethylene-responsive elements (EREs), containing an 11-bp sequence (TAAGAGCCGCC), that act as transcriptional activators or repressors of gene expression under ethylene treatment in tobacco andArabidopsis[18,19]. Heat-shock promoters have been appraised during high-temperature stress experiments in transgenic soybean andArabidopsis[20,21]. Furthermore, many core functional promoter regions have also been identified. The − 148-bp region of the grape C4C4-type RING-finger gene promoter has been demonstrated to be the core functional promoter region and plays a key role in response to heat stress [22], whereas theCsSUS1ppromoter fromCitrus sinensiswas found to be induced in response to wounding of the phloem tissue of transgenic tobacco plants [23]. Deletion analysis of the maize type-II H+-pyrophosphatase gene promoter in transgenic tobacco plants has revealed that a 71-bp segment (− 219 to − 148 bp) is the key region regulating theZmGAPPresponse to NaCl or PEG stress [24]. Furthermore, the expression levels of GUS in transgenic tobacco indicated that a 348-bp fragment of theSbGSTUpromoter could be used for both constitutive and stress-inducible expression of genes [25]. Similarly, GUS transient assays in tobacco leaves have indicated that a 113-bp segment (− 467 to − 355 bp) from the maize phosphatidylinositol synthase gene (ZmPIS) is sufficient for the NaCl or PEG stress response and is considered to be the key sequence for theZmPISresponse to NaCl or PEG treatment [26]. In addition, stress-inducible gene expression requires the interaction between transcription factors andcis-acting elements in the promoter, thereby highlighting the need for functional validation of gene promoter activity in response to signalling molecules and abiotic stresses.

The oriental melon (Cucumis melovar.makuwaMakino), which has shallow roots and large thin leaves, is an important agricultural commodity and widely grown in China and other eastern Asian countries. Abiotic stresses, such as low temperature, drought, high salinity, and mechanical damage, are all unfavourable to the growth and development of melon. With the release of the entire genome sequence of melon, a new resource for the functional analysis of LOX genes in this plant has emerged [27]. To date, 18 candidateLOXgenes have been identified in the melon genome, which have been grouped into three categories (type I 9-LOX, type I 13-LOX, and type II 13-LOX) based on phylogenetic analysis [28]. Previous studies have shown that the expression levels of melonCmLOX08,CmLOX10,CmLOX12,CmLOX13, andCmLOX18genes differ in response to different signal molecule and abiotic stress treatments, indicating that these five genes may play diverse functional roles in melon [29].

Phylogenetic analysis has indicated thatCmLOX08(MELO3C011885) is a member of the type II 13-LOX genes, and is known to play an important role in biotic and abiotic stress responses [4,28,30,31]. It has previously been shown thatCmLOX08is induced in response to various stresses, including wounding, heat, and cold, or signalling molecules such as H2O2[29]. To date, however, there have been no reports describing the mechanisms whereby the expression ofCmLOX08is regulated in response to abiotic stress. In this study, we cloned theCmLOX08promoter from young leaves of the ‘Yumeiren’ cultivar of oriental melon based on sequences in melon genome databases and sought to identify putativecis-regulatory elements that respond to signalling molecules and abiotic stresses. To identify regions of theCmLOX08promoter that play a role in regulating transcription, we constructed five promoter 5′-deletion vectors using pBI121 and examined their responses in tobacco leaves subjected to a range of different signalling molecules and abiotic stresses usingAgrobacterium-mediated transient assays. The findings of these analyses will contribute to gaining a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the response ofCmLOX08to abiotic stress in oriental melon.

Results

Isolation and sequence analysis of theCmLOX08promoter

On the basis of the publicly available sequence in the melon genome database (http://melonomics.net), we obtained the 2054-bp 5′ flanking sequence ofCmLOX08upstream of the ATG start codon from melon genomic DNA. Two alignments of the promoter sequence ofCmLOX08-pro were performed based on the sequence obtained and that from the melon (Cucumis melonL.) genome database (GeLOX08-pro) using DNAMAN software. The results showed that the nucleotide sequences ofCmLOX08-pro andGeLOX08-pro shared 99.61% identity. However, compared withGeLOX08-pro,CmLOX08-pro was found to have a larger number of nucleotides containing a single adenine and fewer nucleotides containing three thymines (Additional file1).

Analysis ofcis-regulatory elements in theCmLOX08promoter

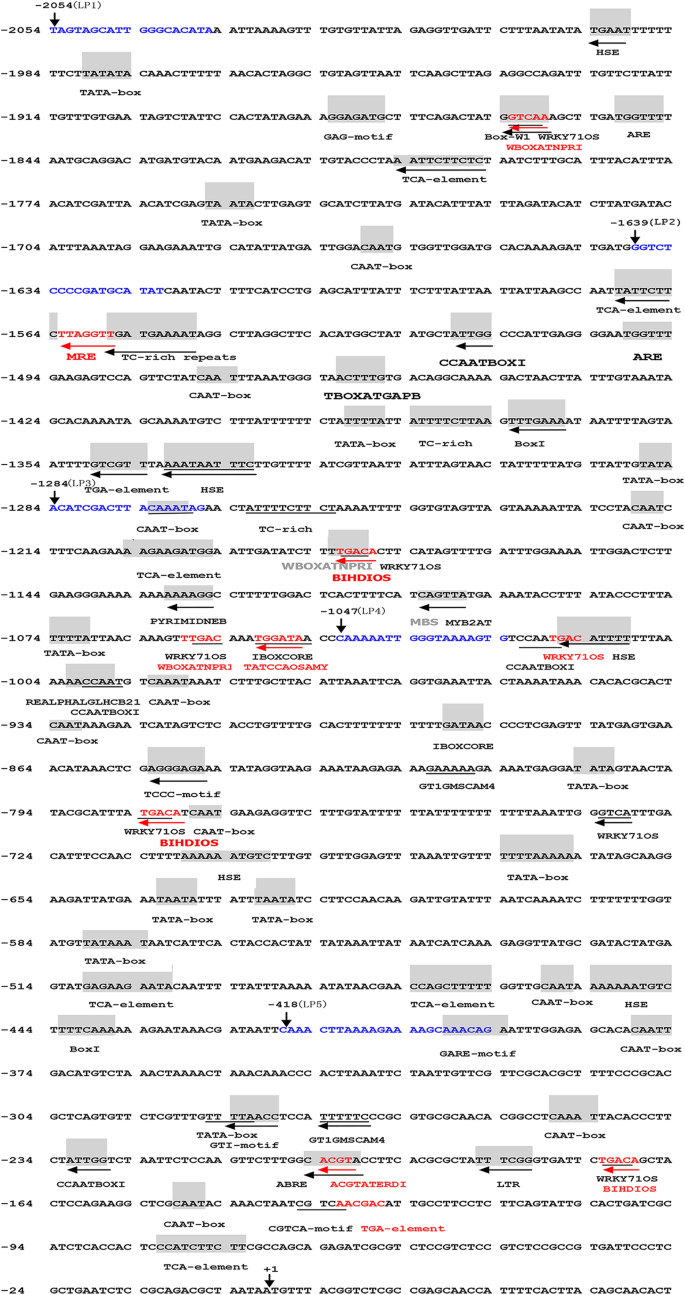

TheCmLOX08promoter sequence was characterized using the online software PlantCARE and PLACE. Thirty types of potentialcis-acting elements were detected within the 2054-bp region of theCmLOX08promoter (Fig.1and Table1).

Nucleotide sequence of theCmLOX08promoter. The “A” of the translation initiation code “ATG” ofCmLOX08was designated as “+ 1”. Putativecis-acting elements are underlined, shadowed, colored and labeled. The horizontal arrows show their directions. See Table1for descriptions of the elements. The vertical arrow above the sequence indicates the start point of different deletion fragments; the blue nucleotide sequences represent special primers for amplifying deletion fragments (LP1–LP5)

Multiple corecis-acting elements, including 11 TATA and 11 CAAT boxes, were identified at numerous positions. Furthermore, a series of putativecis-regulatory elements that facilitate the inducible expression ofCmLOX08were detected, including eight types of light-responsive elements (GAG-motif, MRE, TBOXATGAPB, Box I, IBOXCORE, REALPHALGLHCB21, TCCC-motif, and GT1-motif), nine types of hormone-responsive elements (WRKY71OS, WBOXATNPR1, TCA-element, TGA-element, PYRIMIDINEB, TATCCAOSAMY, GARE-motif, ABRE, and CGTCA-motif), twocis-acting elements involved in heat stress responsiveness (HSE and CCAATBOX1), acis-acting element involved in low-temperature-induced expression (LTR), an element involved in pathogen- and salt-induced SCaM-4 gene expression (GT1GMSCAM4), a MYB binding site involved in drought inducibility (MBS), an ATMYB2 binding site and an element related to dehydration-responsive genes (MYB2AT and ACGTATERD1, respectively), an enhancer-like element involved in anaerobic inducibility (ARE), a fungal-inducible element (Box-W1), a binding site of OsBIHD1 involved in disease resistance responses, and three TC-rich repeats involved in defence and stress responsiveness.

Activities of theCmLOX08promoter in response to signalling molecule treatments

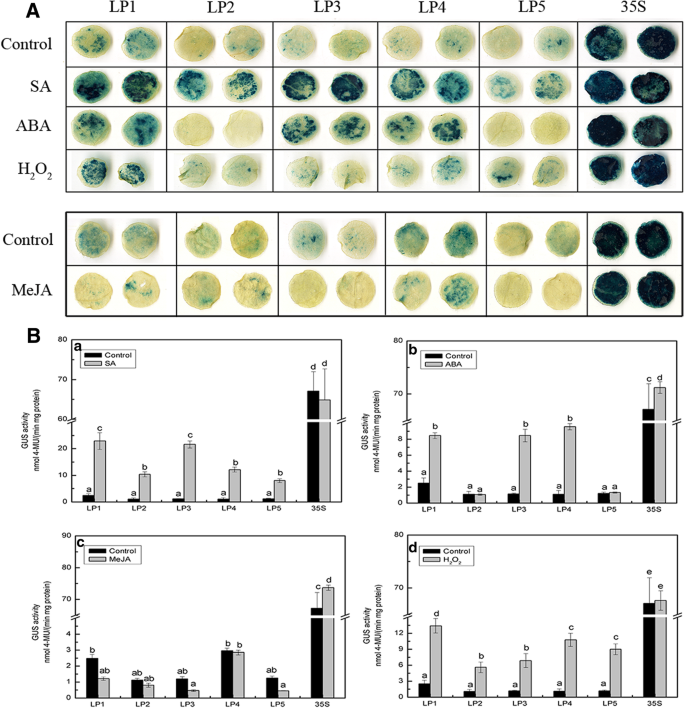

To determine the role of putativecis-regulatory elements in the response of theCmLOX08promoter to signalling molecules, tobacco leaves infiltrated withAgrobacteriumharbouringCmLOX08五个不同的启动子片段删除愣了ths were treated with SA, ABA, MeJA, and H2O2, followed by GUS histochemical staining and fluorometric assay analyses (Fig.2).

Analysis of differentCmLOX08promoter deletion constructs in tobacco plants under signaling molecules treatments.AGUS histochemical staining of five deletions constructs under SA, ABA, H2O2, and MeJA treatments.BGUS activity of different deletion constructs under SA(a), ABA(b), MeJA(c), and H2O2(d)treatments. Values represent the means ± SD from three repeats. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences atP < 0.05

In response to treatment with SA, each of the five deletion structure was intensely stained and the GUS activity of the LP1–LP5 promoter fragments was significantly increased by 9.18-, 9.48-, 18.65-, 10.99-, and 6.66-fold, respectively, compared with the mock-treated control after treatment with SA (Fig.2A, B, a). These results indicate that at least one SA-responsive element is located in the promoter region from − 418 to − 1, although additionalcis-elements could be present in regions further upstream. After treatment with ABA, the LP1, LP3, and LP4 promoter constructs were strongly stained compared with the control, whereas the LP2 and LP5 constructs remained unstained (Fig.2A). We observed that GUS activity increased significantly for the LP1, LP3, and LP4 fragments, whereas no significant change was detected for LP2 and LP5 (Fig.2B, b). These results indicate that the promoter regions from − 2054 to − 1639 and − 1284 to − 418 play a positive role in the response to ABA and may contain thecis-element that responds positively to ABA treatment. Furthermore, we found that the promoter region from − 1639 to − 1284 may contain repressor elements that respond negatively to ABA treatment. In response to treatment with MeJA, we were unable to detect any significant staining or GUS activity in any of theCmLOX08promoter deletion fragments in comparison with the control treatment (Fig.2A, B, c). For H2O2treatment, the changes in GUS activity were consistent with those observed following SA treatment (Fig.2B, d). Accordingly, these findings indicate that, whereas theCmLOX08promoter responds positively to ABA, SA, and H2O2, it shows no detectable response to MeJA.

Analysis of abiotic stress-induced activity of theCmLOX08promoter

To examine the activity of theCmLOX08promoter in response to environmental stress and to identify the correspondingcis-regulatory regions, tobacco plants infiltrated withAgrobacteriumharbouringCmLOX08五个不同的启动子片段删除愣了ths were subjected to salt, drought, wounding, heat, and cold stresses.

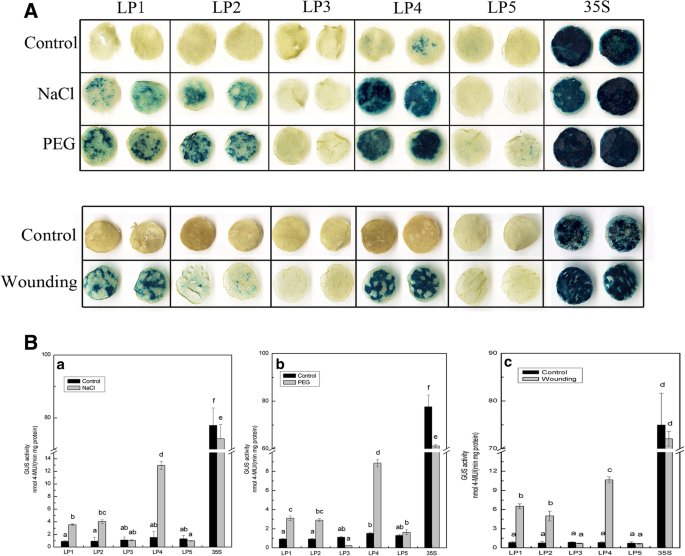

氯化钠和钉治疗,发起人activities of LP1–LP5 were examined in leaves by incubating the detached leaves in half-strength liquid MS medium supplemented with 200 mM NaCl (salt stress treatment) or 18% PEG 6000 (drought stress treatment). pBI121 (35S) (positive control) and p121GUS (negative control) plants were also treated in parallel. In response to osmotic stress (NaCl or PEG) treatments, there was a significant increase in the inducible GUS activity of leaves harbouring the LP1, LP2, and LP4 deletion fragments, whereas no significant changes were detected for the LP3 and LP5 fragments when compared with the untreated controls (Fig.3B, a and b). Furthermore, we observed that induced GUS activity was highest in the LP4 fragment (the promoter region from − 1047 to − 1), indicating that this region contains elements of a salt- or drought-inducible nature and may promote high levels of gene expression. In response to wounding treatment, the GUS activity induced by LP1, LP2, and LP4 fragments increased by 7.74-, 6.69-, and 12.77-fold, respectively, compared with the control, whereas that induced by LP3 and LP5 remained stable (Fig.3B, c). These results indicate that there are no wounding-responsive-elements present in the − 418 to − 1 region of theCmLOX08promoter, whereas in contrast, the region from − 1047 to − 418 contains majorciselements that respond to wounding treatment.

Analysis ofCmLOX08promoter deletion constructs in tobacco plants under salt, drought and wounding treatments.AGUS histochemical staining of five deletions constructs in tobacco plants under 200 mM NaCl, 18% (w/v) PEG 6000 and wounding treatments.BGUS activity of different deletion constructs in tobacco plants under 200 mM NaCl(a), 18% (w/v) PEG 6000PEG(b)and wounding(c)treatments. Values represent the means ± SD from three repeats

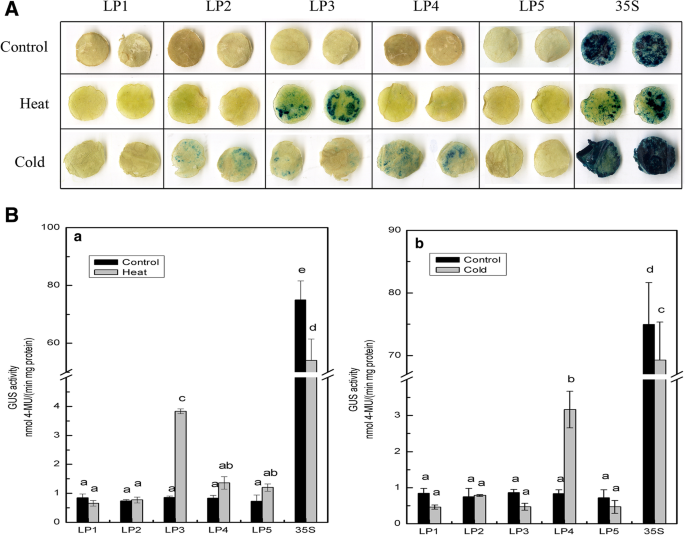

When tobacco leaves were exposed to high temperature treatment, the highest level of GUS activity was detected in the LP3 deletion structure, which increased significantly (4.46-fold) compared with that of the control treatment (Fig.4B, a). However, no significant changes in GUS activity were detected for any of the other deletion fragments, thereby indicating that the keyciselements that respond to heat reside in the − 1284 to − 1047 region of the promoter, and that repressor elements may exist in the − 2054- to − 1284-bp region of theCmLOX08promoter. The results of GUS activity assays under cold treatment were essentially similar to those obtained for heat treatment. Furthermore, the GUS activity of the LP4 deletion structure was 3.79-fold higher than that of the mock-treated control, whereas the other deletion structures showed no significant change compared with the control (Fig.4B, b). Accordingly, these results indicate that the promoter region from − 1047 to − 418 harbours a cold-induciblecis-element and that repressor elements may be present in the − 2054- to − 1047-bp fragment of theCmLOX08promoter.

Analysis of differentCmLOX08promoter deletion constructs under heat or cold treatments.AGUS histochemical staining of five deletions constructs under heat and cold treatments.BGUS activity of different deletion constructs under heat(a)and cold(b)treatments. Values represent the means ± SD from three repeats

In addition to the aforementioned treatments, we also examined GUS activity in positive control tobacco leaves infected withAgrobacteriumharbouring p121GUS:35S, which showed strong GUS activity (Figs.2,3and4), whereas negative control tobacco leaves infected withAgrobacteriumharbouring p121GUS showed no GUS activity (Additional file2).

Discussion

In plants, LOX enzymes are involved in different forms of stress response, including that induced by wounding or different signalling molecules such as MeJA and SA, which are well-known modulators of defence responses [32,33]. To investigate howCmLOX08当东方m基因表达可能是监管elon is subjected to different abiotic stresses, we initially cloned the 2054-bp promoter ofCmLOX08and identified therein severalcis-regulatory elements that are predicted to respond to signalling molecules and environmental stresses, based on reference to the PlantCARE and PLACE databases (Fig.1and Table1). Subsequently, we performed deletion analysis of theCmLOX08promoter, with the aim of determining the major promoter regions that mediate the responses to signalling molecules and abiotic stresses using anAgrobacterium-mediated transient assay in tobacco leaves.

Our data showed that the GUS activity of all the examinedCmLOX08promoter deletion structures was significantly induced after SA treatment (Fig.2B, a). Furthermore, we found that, at numerous positions, theCmLOX08promoter contains a TCA-element, which is acis-acting element involved in SA responsiveness [15]. Thus, the TCA motif may play a role in regulating the expression ofCmLOX08that is similar to that observed inGPPfromActinidia deliciosawhen SA acts as a signal molecule [34]. We observed that the expression level ofCmLOX08was significantly reduced after SA treatment [29], which may due to associated transcription factors that play a negative regulatory role with respect toCmLOX08transcription in response to SA treatment [35,36].

In plants, ABA is a broad-spectrum phytohormone involved in integrating various stress signal transduction pathways during the response to abiotic stresses [37]. The signalling pathways involved in the response to abiotic stress are mainly divided into ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signalling pathways [38,39,40]. These pathways can be regulated by ABREs (abscisic acid-responsive elements), DRE/CRTs (dehydration-responsive element/C repeats), or MYB and MYC recognition motifs [41,42]. Although we detected the presence of ABRE, MYB2AT, and multiple MYB-like (T/AGTTA/T) elements spread across the entire region of theCmLOX08promoter, we were unable to locate any DRE/CRTs elements (Fig.1). Furthermore, we also found that in response to ABA treatment, the GUS expression induced by the promoter deletion fragments LP1, LP3, and LP4 was significantly higher than that in the mock-treated control (Fig.2B, b). On the basis of these observations, we can infer that the ABRE- and MYB-binding sites in the promoter ofCmLOX08may play a significant role in the response to exogenous ABA. Surprisingly, ABA treatment had no effect on the gene expression ofCmLOX08[29], and hence, further studies are needed to determine whetherCmLOX08responds to abiotic stress via an ABA-independent pathway.

Previous studies have shown that ABA, SA, MeJA, and H2O2interact with each other under stress conditions [12]. For example, in tomato, ABA and MeJA were shown to synergistically promote expression of thePIN2gene [43], whereas in the present study, unlike the response to ABA, GUS activity of theCmLOX08promoter was not induced by MeJA (Fig.2B, c), indicating that there may be no interaction between ABA and MeJA in the regulation ofCmLOX08gene expression. Interestingly, the expression ofCmLOX08was significantly down-regulated after 3 h under MeJA treatment [29]. This response may be attributable to other factors that affect the expression ofCmLOX08independently of MeJA treatment.

In contrast, we found that treatment with H2O2resulted in a significant increase in GUS activity of theCmLOX08promoter (Fig.2B, d), which is consistent with the up-regulation ofCmLOX08[29]. In this regard, it is worth noting that theCmLOX08promoter has no H2O2-inducible motifs (Fig.1). These results indicate that certaincis-acting regulatory elements involved in H2O2responsiveness may be present in theCmLOX08promoter. However, the sequences of H2O2-inducible motifs need to be further confirmed.

In our previous studies, we found that NaCl and PEG treatments could promote an up-regulation ofCmLOX08expression levels (Additional file3). The transient expression results obtained in the present study revealed that the GUS activities of promoter deletion fragment LP4 were the highest compared with those of other deletion fragments under NaCl and PEG treatments (Fig.3B, a and b), which indicates that the 1047-bp (LP4) segment may containcis-acting elements that are induced by the aforementioned abiotic stresses. Interestingly, we noted the presence of a GT1GMSCAM4 motif in LP4 (Fig.1), which is acis表演元素参与盐反应(44]. Therefore, collectively, these results indicate that the GT1GMSCAM4 motif may play a role in regulating the expression ofCmLOX08为了应对盐胁迫。相比之下,我们是unable to detect any drought-inducible elements in the 1047-bp (LP4) segment, indicating that this region may contain a hitherto uncharacterized element that is crucial for drought responsiveness. In our wounding treatment, GUS activity was induced by the LP1, LP2, and LP4 promoter fragments (Fig.3B, c), with expression being significantly increased at 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 h after wounding [29]. We noted, however, that there are no recognized associated response elements in theCmLOX08promoter. We did, nevertheless, detect a GARE motif in the 1047-bp (LP4) segment (Fig.1), and although this motif has been recognized as a gibberellin-responsive element in the promoter region ofSFR2inBrassica oleracea, it may play an important role in the response to wounding [45]. Thus, these results tend to indicate that the promoter activity induced by mechanical damage is similar to that induced in response to exogenous stimuli [34,40,46]. Currently, however, we still have very limited knowledge regarding the complex interactions between promoters and transcription factors at the transcriptional level [47]. Accordingly, in order to further elucidate the regulatory mechanism ofCmLOX08in response to abiotic stress, it will be particularly important to study the transcription factors that combine with theCmLOX08promoter under different abiotic stress treatments.

With the exception of LP3, for which GUS activity was significantly increased, we were unable to detect any GUS expression induced by theCmLOX08promoter deletion fragments when we subjected tobacco plants to heat stress (Fig.4B, a). Within the 1047-bp (LP4) region, there are sixcis-acting elements involved in heat stress responsiveness (three HSEs and three CCAATBOX1s), which can bind heat stress transcription factors [48]. However, we unable to detect any heat-inducible elements in the 237-bp region between LP3 and LP4 (Fig.1). Our observation that the GUS activity of LP3 was higher than that of LP4 can probably be attributed to the fact that the 237-bp region between LP3 and LP4 contains enhanced elements involved in defence and stress responsiveness (TC-rich repeats) or contains uncharacterized heat-induciblecis-acting elements [49]. Given thatCmLOX08expression is also significantly induced at various time points after heat treatment [29], we infer that HSE and CCAATBOX1 are the main heat-responsive elements and that TC-rich repeats also play an important role in the response to heat stress.

Low temperature was found to increase the GUS activity of the LP4 deletion structure (Fig.4B, b), which may be attributable to the presence of an LTR element that is responsive to low temperature [50]. Interestingly, low temperature significantly increased the expression ofCmLOX08after 6 h under cold stress [29]. We thus speculate that the LTR motif may play a role in regulating the expression ofCmLOX08in response to cold stress.

Conclusion

In this study, we cloned the promoter region of the oriental melonCmLOX08gene and subsequently sought to identify putativecis-regulatory elements that respond to signalling molecules and abiotic stresses by reference to the PlantCARE and PLACE databases. The results of GUS histochemical staining and fluorescence assays indicated that activity of theCmLOX08promoter is regulated by various signalling molecules and abiotic stresses, and that the promoter generally functions as a signalling molecule/stress-inducible promoter. By analysing the differing responses ofCmLOX08长短不同的启动子缺失片段signalling molecules and abiotic stresses, we were able to characterize the core and positive and negative regulatory regions that show responsiveness to three different signalling molecules and five types of abiotic stress, respectively. The data generated in this study will enrich the existing inducible promoter resources and provide useful information for further study of the mechanisms wherebyCmLOX08is regulated when oriental melon is subjected to different abiotic stresses.

Methods

Plant materials, growth conditions, and bacterial strains

Oriental melons (Cucumis melovar.makuwaMakino) cultivar ‘YuMeiren’, from the Yijianpu Mishijie Melon Research Institution, Changchun, China, were grown individually in a culture room at 25 ± 2 °C, under a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod at Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China. The young leaves of 1-month-old seedlings were harvested, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until used for cloning of theCmLOX08promoter. Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) preserved in our laboratory was raised for 6 weeks in a mix of peat, perlite, and vermiculite (2:1:1,v/v/v) at 25 °C under a 16/8 h day/night cycle followed by using for agro-infiltration.Escherichia colistrain DH5α (Tiangen Biotech, China) was used for the cloning and propagation of all recombinant plasmid vectors, andAgrobacterium tumefaciensstrain GV3101 (Weidi Biotech, China) was used for tobacco leaf infiltration.

Isolation of theCmLOX08promoter

Genomic DNA was isolated from young melon leaves using a NuClean Plant Genomic DNA Kit (Kangwei Biotech, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol and used for cloning of theCmLOX08promoter. On the basis of theCmLOX08promoter sequence obtained from the melon genome database (http://melonomics.net, accession number: MELO3C011885), we designed a pair of primers, LOX08pro-F and LOX08pro-R (Table2), which were used to amplify the full-length genomic sequence using melon genomic DNA as a template.CmLOX08promoter fragments were amplified using high-fidelity PrimeSTAR™ HS DNA polymerase (Takara, Japan) in a 50-μL reaction mix containing 2 μL genomic DNA and 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer. The PCR amplification conditions were as follow: 30 cycles of 10 s at 98 °C, 15 s at 54 °C, and 2.5 min at 72 °C, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified fragments of approximately 2 kb in size were purified using a MiniBEST Agarose Gel DNA Extraction Kit (Takara, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocols, and inserted via TA-cloning into the pMD18-T vector (Takara, Japan) following the addition of poly A tails (Additional file4). Plasmids containing inserts of the expected size, identified by plasmid PCR, were sequenced by Invitrogen (Shanghai, China). Finally, we obtained a 2054-bp fragment upstream of the translation start codon ofCmLOX08, which was considered to be the full-length promoter and was designated pLOX08-pro.

Analysis ofcis-regulatory elements in theCmLOX08promoter

On the basis of the cloned and sequenced fragments, sequence analysis of thecis-regulatory elements of theCmLOX08promoter was performed using PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) and PLACE (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/) databases [51,52].

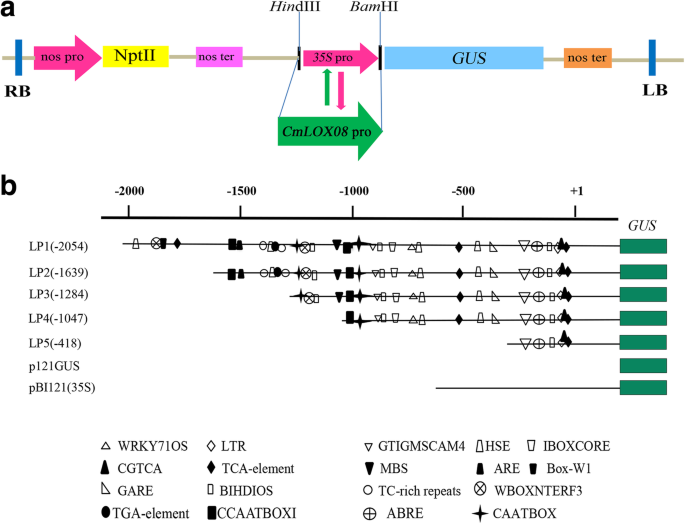

Construction ofCmLOX08promoter::GUS plasmids

For functional validation of theCmLOX08promoter, five 5′-deletion fragments encompassing different lengths of theCmLOX08promoter (− 2054 bp, − 1639 bp, − 1284 bp, − 1047 bp, and − 418 bp to − 1 bp), and containingHindIII andBamHI restriction sites, were amplified using five sets of specific PCR primers (Table2) and two PCR reactions according to a method described in the literature [53]. Using this method, the fact that the inserted fragment might have the same restriction site as the vector used in the subsequent step was not a relevant consideration. Using the pLOX08-pro plasmid as template DNA, the 2054-bpCmLOX08promoter fragments containing eitherHindIII orBamHI restriction sites were amplified using the first (LP1-F1 and LP-R1) and second (LP1-F2 and LP-R2) pair of primers, respectively, to eventually generate two different PCR fragments. Similarly, two different PCR fragments for the other four deletion fragments of theCmLOX08promoter (1639, 1284, 1047, and 418 bp) were acquired using the same primer pairs (Table2). PCR reactions were performed with high-fidelity PrimeSTAR™ HS DNA Polymerase (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using the same PCR conditions as described above. The PCR products were purified using a MiniBEST Agarose Gel DNA Extraction Kit (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Similar amounts of the two different purified PCR fragments of theCmLOX08promoter, acquired as described above, were added to a 50-μL reaction mixture containing 1 μL T4 polynucleotide kinase (Takara, Japan) and 1 μL 100 mM ATP (Takara, Japan). PCR was performed using the following reaction conditions: 90 min at 37 °C, 5 min at 95 °C, and 10 min at 25 °C. Mixtures containing DNA fragments of theCmLOX08promoter were subsequently ligated into the pBI121 binary expression vector digested withHindIII andBamHI (Takara, Japan) using T4 DNA ligase (Takara, Japan) to generate the recombinant vector designated LP1, in which theCaMV35Spromoter of vector pBI121 was replaced with the 2054-bpCmLOX08promoter fragment. Recombinant vectors containing the other four promoter deletion fragments were constructed using the same method and designated LP2 (1639 bp), LP3 (1284 bp), LP4 (1047 bp), and LP5 (418 bp), respectively (Fig.5). The five different recombinant vectors were verified by plasmid PCR (Additional file5) and sequenced prior to being transformed intoAgrobacterium tumefaciensstrain GV3101 using the freeze–thaw transformation technique. In addition, the pBI121 (p121GUS:35S) vector was used as positive control and p121GUS was used as a negative control. The recombinant vector p121GUS was generated from the pBI121 vector by digesting withHindIII andBamHI (Takara, Japan) to excise theCaMV 35Spromoter, followed by filling the 5′ overhangs of the linearized vector with T4 DNA polymerase (Takara, Japan) and ligating the blunt ends using T4 DNA ligase (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transient transformation of tobacco plants withCmLOX08promoter::GUS constructs.aSchematic representation ofCmLOX08promoter::GUS vector constructs. NPT II, neomycin phosphotransferase II gene; nos ter, nopaline synthase terminator; GUS, β- glucosidase gene. RB and LB, left and right T-DNA borders. The insertion position of the CmLOX08 promoter in the vector is indicated with restriction enzyme sites (HindIII andBamHI).bSchematic representation of the different 5’deletionCmLOX08promoter constructs used to assay GUS activity in tobacco leaves. These constructs are based on the pBI121vector. The maincis-elements are represented with different patterns

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression assay

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression assays were performed as described previously [54,55]. A single colony ofAgrobacteriumstrain GV3101 harbouring one of the five different recombinant binary vectors was inoculated into 2 mL YEB medium supplemented with 50 μg mL− 1rifampicin and 50 μg mL− 1kanamycin and grown at 28 °C and 200 rpm for 24 h. Thereafter, 1 mL of the resulting culture was transferred into 50 mL YEB medium containing 50 μg mL− 1rifampicin, 50 μg mL− 1kanamycin, 10 mM ethanesulfonic acid (pH 5.7 MES), and 20 μM acetosyringone (AS) and grown at 28 °C and 200 rpm for 24 h. TheAgrobacteriumcells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature, and following the removal of supernatant, the pelleted cells were resuspended in infiltration medium (10 mM pH 5.7 MES, 10 mM MgCl2, and 150 μM AS). The cell suspension was diluted to OD600 = 0.8 using infiltration medium, and then incubated at room temperature for 3 h in the dark. TheAgrobacteriumsuspensions harbouring recombinant binary vectors were then injected into the abaxial surfaces of the leaves of 6-week-old tobacco plants using a 1-mL needleless syringe. The inoculated tobacco plants were subsequently maintained in a growth cabinet under a 16/8 h day/night cycle at 25 °C for 48 h.

Signalling molecule and abiotic stress treatments

For analysis of thecis-regulatory element of theCmLOX08promoter, agro-infiltrated tobacco plants were treated with SA, ABA, MeJA, and H2O2to characterize promoter induction in response to signalling molecule treatments. For SA, ABA, and H2O2treatments, the tobacco plants were sprayed with 1 mM SA, 0.1 mM ABA, or 10 mM H2O2in distilled water, respectively, whereas control plants were sprayed with distilled water. For MeJA treatment, the tobacco plants were sprayed with 0.1 mM MeJA dissolved in 10% ethanol and control plants were sprayed with 10% ethanol.

We also exposed the agro-infiltrated tobacco plants to a variety of abiotic stresses, namely, low and high temperatures, mechanical wounding, salinity, and drought, to characterize the extent to which promoter activation occurs in response to these stresses. For the low and high temperature treatments, the plants were maintained in a growth cabinet at 4 °C or 42 °C, respectively. For the wounding treatment, the tobacco leaves (an area of approx. 20 cm2) were pricked 200 times with the needle of a 10-mL syringe. Control tobacco plants were placed in a growth cabinet at 25 °C without any treatment.

For salinity and drought stress treatments, we followed the methods described by Hou et al. [24]. Leaf discs obtained from infiltrated plants were floated on half-strength liquid MS medium supplemented with either 200 mM NaCl (salt stress treatment) or 18% (w/v) PEG 6000 (drought stress treatment) for 24 h. Infiltrated leaves incubated in half-strength liquid MS medium were considered a control.

The leaves of the tobacco plants subjected to signalling molecule and abiotic stress treatments and their controls were used for GUS analysis after 24 h. All experiments were repeated three times.

Histochemical staining and fluorometric assays for detecting GUS activity

Histochemical staining was performed in accordance with the procedures described by Jefferson [56]. Tobacco leaves were punched with a hole punch to obtain leaf discs with a diameter of 1 cm and these were incubated in GUS staining solution [50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM X-Gluc (Sangon, Shanghai, China), and 0.1% Triton X-100] at 37 °C for 24 h. After staining, the tissues were bleached with 70% ethanol and photographed using a scanner.

Transient expression of GUS activity in the treated tobacco leaves was measured as described previously [57]. Tobacco leaf tissue (0.15 g) was homogenized in an extraction buffer [50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% (w/v) sodium dodecylsulfate, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol] at 4 °C, and centrifuged at 12,000×gfor 15 min at 4 °C. Aliquots (100 μL) of the resulting supernatant were mixed with 600 μL GUS assay solution [1 mM methyl-4-umbelliferyl-d葡糖苷酸提取缓冲(4-MUG),σ,USA] pre-warmed to 37 °C and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. A portion of this mixture (100 μL) was then added to 900 μL stop buffer (0.2 M Na2CO3). Fluorescence was measured using a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Agilent, USA) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 365 nm and 455 nm, respectively. Stop buffer and 10 nM to 80 nM 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) were used for calibration and standardization. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford protein assay kit (Takara, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions with bovine serum albumin used as a standard. GUS activity is presented as nM of 4-MU generated per min per mg soluble protein. GUS measurements were repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean values ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments and were analysed using SPSS statistical software (IBM SPSS statistics 18.0, Chinese version) using an independent samplettest. APvalue ≤0.05 was considered significant. Charts presenting data were generated using Origin software (version 8.0).

Abbreviations

- ABA:

-

Abscisic acid

- AS:

-

Acetosyringone

- GUS:

-

β-Glucuronidase

- H2O2:

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- JA:

-

Jasmonic acid

- LOX:

-

Lipoxygenase

- MeJA:

-

Methyl jasmonate

- MES:

-

Ethanesulfonic acid

- MgCl2:

-

Magnesium chloride

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- SA:

-

Salicylic acid

References

- 1.

Feussner I, Wasternack C. The lipoxygenase pathway. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:275–97.

- 2.

Andreou A, Feussner I. Lipoxygenases - structure and reaction mechanism. Phytochemistry. 2009;70(13–14):1504–10.

- 3.

Prost I, Dhondt S, Rothe G, Vicente J, Rodriguez MJ, Kift N, Carbonne F, Griffiths G, Esquerre-Tugaye MT, Rosahl S, et al. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activities of plant oxylipins supports their involvement in defense against pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2005;139(4):1902–13.

- 4.

Christensen SA, Nemchenko A, Borrego E, Murray I, Sobhy IS, Bosak L, DeBlasio S, Erb M, Robert CA, Vaughn KA, et al. The maize lipoxygenase,ZmLOX10, mediates green leaf volatile, jasmonate and herbivore-induced plant volatile production for defense against insect attack. Plant J. 2013;74(1):59–73.

- 5.

Hu T, Zeng H, Hu Z, Qv X, Chen G. Overexpression of the tomato 13-lipoxygenase geneTomloxDincreases generation of endogenous jasmonic acid and resistance toCladosporium fulvumand high temperature. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2013;31(5):1141–9.

- 6.

Yan L, Zhai Q, Wei J, Li S, Wang B, Huang T, Du M, Sun J, Kang L, Li CB, et al. Role of tomato lipoxygenase D in wound-induced jasmonate biosynthesis and plant immunity to insect herbivores. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(12):e1003964.

- 7.

Lim CW, Han S-W, Hwang IS, Kim DS, Hwang BK, Lee SC. The pepper lipoxygenase CaLOX1 plays a role in osmotic, drought and high salinity stress response. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(5):930–42.

- 8.

Hou Y, Meng K, Han Y, Ban Q, Wang B, Suo J, Lv J, Rao J. The persimmon 9-lipoxygenase geneDkLOX3plays positive roles in both promoting senescence and enhancing tolerance to abiotic stress. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1073.

- 9.

Wang R, Shen W, Liu L, Jiang L, Liu Y, Su N, Wan J. A novel lipoxygenase gene from developing rice seeds confers dual position specificity and responds to wounding and insect attack. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66(4):401–14.

- 10.

Padilla MN, Hernandez ML, Sanz C, Martinez-Rivas JM. Molecular cloning, functional characterization and transcriptional regulation of a 9-lipoxygenase gene from olive. Phytochemistry. 2012;74:58–68.

- 11.

Li S-t, Zhang M, Fu C-h, Xie S, Zhang Y, L-j Y. Molecular cloning and characterization of two 9-lipoxygenase genes fromTaxus chinensis. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2012;30(6):1283–90.

- 12.

Yang XY, Jiang WJ, Yu HJ. The expression profiling of the lipoxygenase (LOX) family genes during fruit development, abiotic stress and hormonal treatments in cucumber (Cucumis sativusL.). Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(2):2481–500.

- 13.

Gao X, Stumpe M, Feussner I. Kolomiets M. A novel plastidial lipoxygenase of maize (Zea mays)ZmLOX6encodes for a fatty acid hydroperoxide lyase and is uniquely regulated by phytohormones and pathogen infection. Planta. 2008;227(2):491–503.

- 14.

Wang LW, He MW, Guo SR, Zhong M, Shu S, Sun J. NaCl stress inducesCsSAMsgene expression inCucumis sativusby mediating the binding ofCsGT-3bto the GT-1 element within theCsSAMspromoter. Planta. 2017;245(5):889–908.

- 15.

Goldsbrough AP, Albrecht H, Stratford R. Salicylic acid-inducible binding of a tobacco nuclear protein to a 10 bp sequence which is highly conserved amongst stress-inducible genes. Plant J. 1993;3(4):563–71.

- 16.

Guiltinan MJ, Marcotte WR Jr. A plant leucine zipper protein that recognizes an abscisic acid response element. Science. 1990;250(4978):267.

- 17.

Hobo T, Asada M, Kowyama Y, Hattori T. ACGT-containing abscisic acid response element (ABRE) and coupling element 3 (CE3) are functionally equivalent. Plant J. 1999;19(6):679–89.

- 18.

Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factor act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. Plant Cell. 2000;12:393–404.

- 19.

Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell. 1995;7:173–82.

- 20.

Chauhan H, Khurana N, Nijhavan A, Khurana JP, Khurana P. The wheat chloroplastic small heat shock protein (sHSP26) is involved in seed maturation and germination and imparts tolerance to heat stress. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2012;35(11):1912–31.

- 21.

Crone D, Rueda J, Martin KL, Hamilton DA, Mascarenhas JP. The differential expression of a heat shock promoter in floral and reproductive tissues. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2001;24(8):869–74.

- 22.

Yu Y, Xu W, Wang J, Wang L, Yao W, Xu Y, Ding J, Wang Y. A core functional region of theRFP1promoter from Chinese wild grapevine is activated by powdery mildew pathogen and heat stress. Planta. 2013;237(1):293–303.

- 23.

Singer SD, Hily JM, Cox KD. Thesucrose synthase-1promoter fromCitrus sinensisdirects expression of theβ-glucuronidasereporter gene in phloem tissue and in response to wounding in transgenic plants. Planta. 2011;234(3):623–37.

- 24.

Hou J, Jiang P, Qi S, Zhang K, He Q, Xu C, Ding Z, Zhang K, Li K. Isolation and functional validation of salinity and osmotic stress inducible promoter from the maize type-II H+-pyrophosphatase gene by deletion analysis in transgenic tobacco plants. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0154041.

- 25.

Tiwari V, Patel MK, Chaturvedi AK, Mishra A, Jha B. Functional characterization of the tau class glutathione-S-transferases gene (SbGSTU) promoter ofSalicornia brachiataunder salinity and osmotic stress. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148494.

- 26.

Zhang H, Hou J, Jiang P, Qi S, Xu C, He Q, Ding Z, Wang Z, Zhang K, Li K. Identification of a 467 bp promoter of maize phosphatidylinositol synthase gene (ZmPIS) which confers high-level gene expression and salinity or osmotic stress inducibility in transgenic tobacco. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:42.

- 27.

Garcia-Mas J, Benjak A, Sanseverino W, Bourgeois M, Mir G, González VM, Hénaff E, Câmara F, Cozzuto L, Lowy E, et al. The genome of melon (Cucumis meloL.). PNAS. 2012;109(29):11872–7.

- 28.

Zhang C, Jin Y, Liu J, Tang Y, Cao S, Qi H. The phylogeny and expression profiles of the lipoxygenase (LOX) family genes in the melon (Cucumis meloL.) genome. Sci Hortic. 2014;170:94–102.

- 29.

J-y L, Zhang C, Shao Q, Y-f T, S-x C, X-o G, Y-z J, Qi H-y. Effects of abiotic stress and hormones on the expressions of five 13-CmLOXsand enzyme activity in oriental melon (Cucumis melovar.makuwaMakino). J Integr Agric. 2016;15(2):326–38.

- 30.

Halitschke R, Baldwin IT. Antisense LOX expression increases herbivore performance by decreasing defense responses and inhibiting growth-related transcriptional reorganization inNicotiana attenuata. Plant J. 2003;36(6):794–807.

- 31.

Nemchenko A, Kunze S, Feussner I, Kolomiets M. Duplicate maize 13-lipoxygenase genes are differentially regulated by circadian rhythm, cold stress, wounding, pathogen infection, and hormonal treatments. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(14):3767–79.

- 32.

Bhardwaj PK, Kaur J, Sobti RC, Ahuja PS, Kumar S.LipoxygenaseinCaragana jubataresponds to low temperature, abscisic acid, methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid. Gene. 2011;483(1–2):49–53.

- 33.

Porta H, Figueroa-Balderas RE, Rocha-Sosa M. Wounding and pathogen infection induce a chloroplast-targeted lipoxygenase in the common bean (Phaseolus vulgarisL.). Planta. 2008;227(2):363–73.

- 34.

Li J, Li M, Liang D, Cui M, Ma F. Expression patterns and promoter characteristics of the gene encodingActinidia deliciosaL-galactose-1-phosphate phosphatase involved in the response to light and abiotic stresses. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(2):1473–85.

- 35.

Zhao Y, Zhou J, Xing D. Phytochrome B-mediated activation of lipoxygenase modulates an excess red light-induced defence response inArabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(17):4907–18.

- 36.

Tyagi AK. Plant genes and their expression. Curr Sci. 2001;80(2):161–9.

- 37.

Agarwal PK, Jha B. Transcription factors in plants and ABA dependent and independent abiotic stress signalling. Biol Plant. 2010;54(2):201–12.

- 38.

Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki AK. Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:781–803.

- 39.

Xiong L, Schumaker KS, Zhu J-K. Cell signaling during cold, drought, and salt stress. Plant Cell. 2002;14:S165–83.

- 40.

Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:247–73.

- 41.

Mahajan S, Tuteja N. Cold, salinity and drought stresses: an overview. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;444(2):139–58.

- 42.

安倍h .拟南芥AtMYC2 (bHLH)和AtMYB2 (MYB)function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2003;15(1):63–78.

- 43.

Peña-Cortés H, Prat S, Atzorn R, Wasternack C, Willmitzer L. Abscisic acid-deficient plants do not accumulate proteinase inhibitor II following systemin treatment. Planta. 1996;198(3):447–51.

- 44.

Park HC, Kim ML, Kang YH, Jeon JM, Yoo JH, Kim MC, Park CY, Jeong JC, Moon BC, Lee JH, et al. Pathogen- and NaCl-induced expression of the SCaM-4 promoter is mediated in part by a GT-1 box that interacts with a GT-1-like transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2004;135(4):2150–61.

- 45.

Pastuglia M, Roby D, Dumas C, Cock JM. Rapid induction by wounding and bacterial infection of anSgene family receptor-like kinase gene inBrassica oleracea. Plant Cell. 1997;9:49–60.

- 46.

Li J, Cui M, Li M, Wang X, Liang D, Ma F. Expression pattern and promoter analysis of the gene encoding GDP-d-mannose 3′,5′-epimerase under abiotic stresses and applications of hormones by kiwifruit. Sci Hortic. 2013;150:187–94.

- 47.

Agius F, Amaya I, Botella MA, Valpuesta V. Functional analysis of homologous and heterologous promoters in strawberry fruits using transient expression. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(409):37–46.

- 48.

Sung D-Y, Kaplan F, Lee K-J, Guy CL. Acquired tolerance to temperature extremes. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8(4):179–87.

- 49.

Diaz-De-Leon F, Klotz K, Lagrimin LM. Nucleotide sequence of the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) anionic peroxidase gene. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:1117–8.

- 50.

Jiang C, Iu B, Singh J. Requirement of a CCGACcis-acting element for cold induction of theBN115gene from winterBrassica napus. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:679–84.

- 51.

Lescot M, Dhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Peer YVD, Rouz P, Rombauts S. PlantCARE, a database of plantcis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools forin silicoanalysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):325–7.

- 52.

Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):297–300.

- 53.

Simpson R. Purifying proteins for proteomics: a laboratory manual. United States: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2003.

- 54.

Xu W, Yu Y, Ding J, Hua Z, Wang Y. Characterization of a novel stilbene synthase promoter involved in pathogen- and stress-inducible expression from Chinese wildVitis pseudoreticulata. Planta. 2010;231(2):475–87.

- 55.

Yang Y, Li R, Qi M. In vivo analysis of plant promoters and transcription factors by agroinfiltration of tobacco leaves. Plant J. 2000;22(6):543–51.

- 56.

Jefferson RA. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol Biol Report. 1987;5(4):387–405.

- 57.

Jefferson RA. Plant Reporter Genes: The Gus Gene Fusion System. In: Setlow JK (ed) Gen Eng 1988;10:247–263.

Acknowledgements

The authors really appreciate Jieying Liu, Lili Zhao, Zhiran Wang and Bin Yang for the assistance of experiment and result analysis.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471868), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-25) and Shenyang Science and Technology Project (17–143–3-00).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

CW contributed to the experimental design, oriental melon planting and sampling, tobacco planting and experimenting, data processing and result analysis and writing. GG, SC and QX contributed to tobacco sampling and experimenting. HQ defined the work objectives and technical approach, and contributed to the experimental design, result analysis and writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences ofCmLOX08-pro andGeLOX08-pro.CmLOX08-pro promoter: oriental melon (Cucumis melovar.makuwaMakino);GeLOX08-pro promoter: the melon (Cucumis melonL.) genome database. Identical and dissimilar nucleotides are shown on a background of blue and gray, respectively. The two primers LOX08pro-F and LOX08pro-R which cloned theCmLOX08promoter are indicated by arrows. The translation initiation codon (ATG) is framed and marked for “+ 1”. (PDF 498 kb)

额外的文件2:

GUS组织化学染色的p121GUS烟草leaves as negative control. (PDF 125 kb)

Additional file 3:

Expressions ofCmLOX08at various time points under 50 mM NaCl (a) and drought (b) treatments. (PDF 148 kb)

Additional file 4:

PCR amplification ofCmLOX08full length promoter. Lane M: DL5000 DNA Marker; lane 1 to 5:CmLOX08full length promoter fragment. (PDF 123 kb)

Additional file 5:

The five different length recombinant vectors were verified by plasmid PCR. Lane M: DL5000 DNA Marker. Lane 1 to 4: LP1 (2054 bp); lane 5 to8: LP2 (1639 bp); lane 9 to 12:LP3 (1284 bp); lane 13 to 16: LP4 (1047 bp); lane 17 to 20: LP5 (418 bp). (PDF 126 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Gao, G., Cao, S.et al.Isolation and functional validation of theCmLOX08promoter associated with signalling molecule and abiotic stress responses in oriental melon,Cucumis melovar.makuwaMakino.BMC Plant Biol19,75 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1678-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Keywords

- Oriental melon

- Lipoxygenase

- Promoter

- Signalling molecule

- Abiotic stress