- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

MYB-CC transcription factor,TaMYBsm3, cloned from wheat is involved in drought tolerance

BMC Plant Biologyvolume19, Article number:143(2019)

Abstract

Background

MYB-CC transcription factors (TFs) genes have been demonstrated to be involved in the response to inorganic phosphate (Pi) starvation and regulate some Pi-starvation-inducible genes. However, their role in drought stress has not been investigated in bread wheat. In this study, theTaMYBsm3genes, includingTaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-D, encoding MYB-CC TF proteins in bread wheat, were isolated to investigate the possible molecular mechanisms related to drought-tolerance in plants.

Results

TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dwere mapped on chromosomes 6A, 6B, and 6D in wheat, respectively.TaMYBsm3genes belonged to MYB-CC TFs, containing a conserved MYB DNA-binding domain and a conserved coiled–coil domain.TaMYBsm3-Dwas localized in the nucleus, and the N-terminal region was a transcriptional activation domain. TaMYBsm3genes were ubiquitously expressed in different tissues of wheat, and especially highly expressed in the stamen and pistil. Under drought stress, transgenic plants exhibited milder wilting symptoms, higher germination rates, higher proline content, and lower MDA content comparing with the wild type plants.P5CS1,DREB2A, andRD29Ahad significantly higher expression in transgenic plants than in wild type plants.

Conclusion

TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dwere associated with enhanced drought tolerance in bread wheat. Overexpression of TaMYBsm3-D increases the drought tolerance of transgenicArabidopsisthrough up-regulatingP5CS1,DREB2A, andRD29A。

Background

Drought is a severe environmental stress influencing the productivity of corps worldwide. Drought tolerance is a complex phenotype in plants, and is associated with diverse metabolic and morphological pathways [1]. Transcriptional regulation contributes to the response of drought stress in plants [2]. It is noteworthy that the transcription factors (TFs) function in the regulation of diverse physiological and biochemical responses to drought stress by activating diverse stress-related genes [3]. Until now, various TFs have been identified to be associated with the drought stress response, including MYB, bZIP, AP2/ERF, NAC, and WRKY [4,5]. The MYB TFs comprise a larg gene family in plants [6].

MYB, firstly discovered in maize, is characterized by containing a MYB DNA-binding domain in its N-terminus that consists of one or more imperfect tandem repeat(s) [7,8]. The MYB TFs participate in many development processes in plants, such as regulation of cell cycle and cell development, controlling of primary and secondary metabolism, and responses to abiotic and biotic stresses [9,10]. To date, massive MYB proteins have been detected in diverse plants, such as rice, wheat,Arabidopsis, grapes, and petunias [11]. It has been reported that PbrMYB21, an MYB TF ofPyrus betulaefolia, can promote drought tolerance by modulating polyamine levels via arginine decarboxylase genes [12]. The up-regulated OsMYB48–1, an MYB TF ofOryza sativa, promotes drought tolerance of rice by influencing the synthesis of ABA [13]. Overexpression of TaODORANT1, an R2R3-type MYB TF ofTriticum aestivum, promotes drought tolerance of tobacco by activating genes associated with stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [14]. The molecular mechanisms underlying MYB proteins functioning on drought tolerance of plants have been intensively studied. A previous study showed that overexpressed abscisic acid (ABA)- and drought-inducible AtMYB96 could activate the wax biosynthesis genes and increase the deposition of cuticular waxes, thereby leading to enhenced drought tolerance inArabidopsis[15]. Moreover, a recent study reported that the TaMYB31s were upregulated under ABA treatment, and overexpressed TaMYB31-B could increase ABA sensitivity during seed germination [16]. Specially, ABA regulates adaptive responses to environmental stresses, and promotes the tolerance to various abiotic stresses including drought [17]. The balance between ABA biosynthesis and catabolism determines its role under drought-stress condition [18]. Thus, the increased drought tolerance are partly attributed to ABA [16].

MYB-CC TFs are the members of the MYB TF superfamily, being characterized by containing a conserved MYB DNA-binding domain and a coiled–coil (CC) domain, which is a potential dimerization motif. [19]. Currently, MYB-CC TFs are demonstrated to be related to the response to inorganic phosphate (Pi) starvation and regulate a series of Pi-starvation-inducible genes [20,21,22]. Nevertheless, its role in drought tolerance has not been reported to our knowledge. Bread wheat (Triticum aestivumL.) is a main food crop in the world. The repercussions of climate change, particularly drought stress, severely affect wheat yield globally. Identification of drought-responsive genes, especially TF genes, may be of benefit by revealing the molecular mechanisms involved in drought responses in plants. Presently, many wheat MYB genes containing full-length gene sequences have been isolated [23], including some drought stress response-associated gene, such asTaMYB31[16]. Given the drought tolerance of MYB genes in wheat and other plants, we hypothesized that MYB-CC TF genes may also play a role in drought stress in bread wheat.

Herein, threeTaMYBsm3homologue genes (TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-D从小麦分离克隆和表征d by screening bacterial artificial chromosomal (BAC) library. The ability ofTaMYBsm3genes in regulating the drought response was investigated inTaMYBsm3-DtransgenicArabidopsis, due to the high conservation ofTaMYBsm3-Din wheat. We for the first time revealed that TaMYBsm3, a MYB-CC TF, was involved in plant drought stress response. Our results may shed light on the molecular mechanism of drought response and improve the cultivation of plant varieties with drought tolerance.

Methods

Cloning ofTaMYBsm3homologue genes

Nested PCR primers (NP), as shown in Table1, were designed to screen BAC libraries [24] ofTriticum aestivum(T. aestivum) cultivar Shimai 15 that containedTaMYBsm3genes according to the expressed sequence tags (EST) (GenBank No. BJ243280). BAC pool plasmids served as template and the PCR programs included 35 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 45 s, and an extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Then three BACs containingTaMYBsm3基因用于构造10 kb subclone图书馆ies using theBamHIsite of the pCC1BAC vector. Three full-length genomic DNA sequences ofTaMYBm3genes were isolated by screening subclone libraries and sequencing subclones. Full-length cDNAs were amplified from a cDNA template of 2-week-old Shimai15 seedlings. The primers (TaMYBsm3-AFL, TaMYBsm3-BFL, and TaMYBsm3-DFL) (Table1) were used to isolate the full-length cDNAs and genomic DNAs of theTaMYBsm3genes were designed on the basis of theTaMYBsm3genomic DNA sequences. The PCR and RT-PCR were amplified using 2 × Pfu PCR MasterMix (TIANGEN BIOTECH, Beijing, China). The PCR program was 95 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 94 °C 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 3–5 min and then at 72 °C for 8 min.

A set of nullisomic-tetrasomic lines ofT. aestivum‘Chinese Spring’ (CS NT) were used for determining the chromosomal location of the TaMYBsm3 homologue genes. Primers used in the chromosomal location ofTaMYBsm3genes (DW) (Table1) were designed in accordance with the differences in DNA sequence. DNA isolated form a nullisomic tetrasomic line of Chinese Spring (NT-CS) was used as the template. The PCR program included 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and an extension at 72 °C for 8 min.

Sequence analysis

Sequence assembly as well as coding region prediction were conducted with Lasergene SeqMan II Module (DNAStar). Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using neighbor-joining and maximum parsimony methods with 1000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA4.1, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on 20 MYBsm3-like proteins (including TaMYBsm3 proteins). In order to make stronger phylogenetic inferences and to test whether they were congruent, we reconstructed trees by Bayesian analysis using MrBayes v. 3.2.2 [× 64]. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the software of ClustalW1.83.

Transactivation assayof TaMYBsm3-D in yeast

A transactivation assay was performed as previously described [25]. The full-length cDNA (TaMYBsm3F), N-terminal region (TaMYBsm3N, 1-148aa), C-terminal region (TaMYBsm3C, 149-386aa), and myb-SHAQKYF region (TaMYBsm3M, 184-308aa) ofTaMYBsm3-Dwere amplified using specific primers (TR1-TR4) (Table1). After being cloned in the pMD18-T plasmid (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), the PCR products were integrated into the GAL4 DNA-binding domain of the pGBKT7 plasmid (Clontech, Shanghai, China) between theBamHI andPstI sites. Then, the recombinants were transformed into yeast strain Y190 (MATa, HIS3, lacZ, rp1, leu2, cyhr2). Next, they were cultured in selection medium (SD/−Trp/−His/−Ade) containing 25 mM 3-amino-1, 2, aminotriazole for 1 day, the β-galactosidase activity was detected by X-gal staining [26].

Subcellular localization assay of the TaMYBsm3-D-GFP fusion protein

The amplification of full-length cDNA sequence ofTaMYBsm3-Dwas performed by PCR using specific primers (TSR) (Table1) and inserted into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300-sGFP between the sites ofXbaI andBamHI. Positive clones were identified by sequencing. The construct was transformed into epidermal cells ofNicotiana benthamiana(N. benthamiana) in accordance with particle bombardment technology. The fluorescence of GFP was observed under a microscope (Leica SP8, Germany).

Real time-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

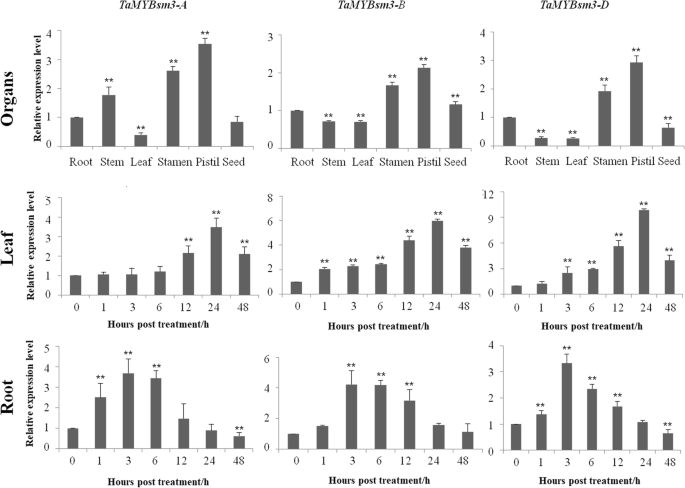

Total RNA was extracted from different tissues (root, stem, leaf, stamen, pistil, and seed) of wild type (WT) plants (Shimai 15) using TRIZOL reagent. Synthesis of first-strand cDNA was conducted using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa). RT-qPCR was performed to detect the expression pattern ofTaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dusing specific primers (WT, WQA, WQB, and WQD) (Table1). The PCR program included 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. Theβ-actingene served as an internal control. The amount of mRNA relative toβ-actinwas calculated using the 2-△△Ctmethod.

In addition, WT plants were treated with 16% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000, and the expression ofTaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dwas detected in leaves and roots at different time points.

Construction of transgenic plants withTaMYBsm3-D

The open reading frame (ORF) ofTaMYBsm3-Dwas amplified with specific primers (TaMYBsm3R) (Table1)和插入到向量pCAMBIA2300包含ing the CaMV35S promoter between theBamHI andPstI sites. The resultant vector was named CaMV35s:TaMYBsm3-D。Then, CaMV35s:TaMYBsm3-Dwas transformed intoArabidopsis thalianacultivar Columbia-0 using theA. tumefaciensstrain GV3101 in accordance with the floral dipping method [27]. Three homozygous transgenic lines (L4, L8, and L13) were confirmed by RT-qPCR and isolated for further assays. In addition, WT plants were treated with 16% PEG8000, and the expression ofTaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dwas detected in leaves and roots at different time points.

Drought stress assay

Phenotypic observation

The transgenic plants together with WT plants (N = 30) were grown for 4 weeks under normal conditions. Then, watering was stopped for 2 weeks. To investigate drought adaptability, plants were re-watered for 2 days, and the phenotypic changes were photographed at different time points. There were three experimental replicates.

Germination assay

The seeds of the WT and transgenic plants (N = 100) were planted in 1/2 MS medium that contained 16% PEG8000. Seeds with radical tip expanding the seed coat were considered as germination. The number of germinated seeds was recorded, and the germination rate was calculated. There were three experimental replicates.

Water-loss assay

The WT plants and transgenic plants (N = 30) were grown for 4 weeks under normal conditions. The fresh weight of aerial parts was recorded every hour until no obvious difference was detected between two adjacent time points. After 24 h of drying at 85 °C, the dry weight was measured. The water-loss rate was calculated as: (fresh weight at different time points - dry weight) / (initial fresh weight - dry weight). There were three experimental replicates.

Proline and malondialdehyde (MDA) detection

The transgenic plants together with WT plants (N = 30) were grown for 4 weeks under normal conditions. After 2 days of drought treatment, rosette leaves were collected. The proline content (nmol g− 1FW) was measured in accordance with the ninhydrin acid reagent method. MDA content was measured as previously described [28]. There were three experimental replicates.

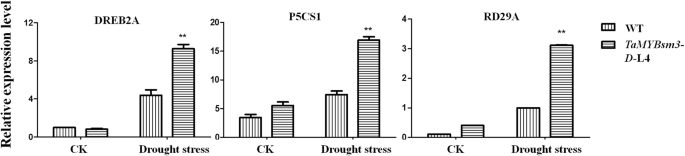

Expression detection of stress-responsive genes

Two-week-old seedlings of transgenic plants together with WT plants (N = 5) were treated with 16% PEG 8000 for 24 h. The expression levels of three downstream drought-stress-related genes,DREB2A,P5CS1, andRD29Awere detected using RT-qPCR with specific primers, as described above (Table1). TheArabidopsisβ-actin was used as internal control. cDNA product was used as template for 40 cycles of 95 °C 2 min, 95 °C 30 s, 59 °C 30 s, 72 °C 30 s. The 2-△△Ctmethod was used for quantitative analysis.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparison between different groups was tested by one-way ANOVA, followed by student’s t-test. Ap-value less than 0.05 was considered significantly different.

Results

Cloning of threeTaMYBsm3homologue genes

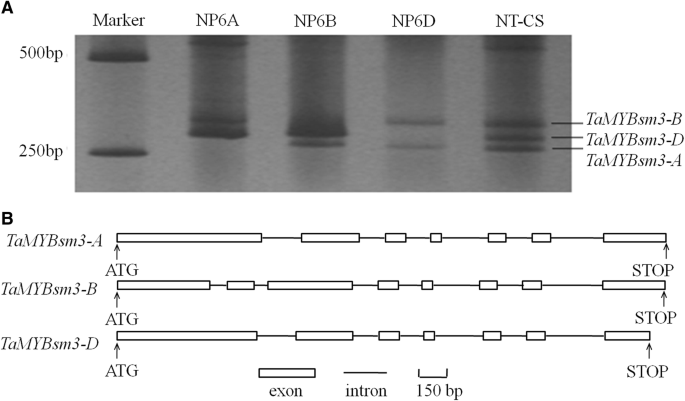

Three full-length genomic DNA sequences containingTaMYBsm3homologue genes (NP6A,NP6B, andNP6D) were cloned in BAC libraries of theT. aestivumcultivar Shimai 15. These three genes were mapped on chromosomes 6A, 6B, and 6D in NT-CS, and named asTaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-D, respectively (Fig.1a). When blasting with the genomic sequence of NT-CS (https://plants.ensembl.org/Triticum_aestivum/Info/Index),TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dwere highly consistent with the sequences on chromosomes 6AS, 6BS, and 6DS, respectively. Sequence analysis showed thatTaMYBsm3-AandTaMYBsm3-Dhad the same gene structures with 7 exons and 6 introns, andTaMYBsm3-Bhad 8 exons and 7 introns. The ORFs ofTaMYBsm2-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dwere 1248 bp, 1152 bp, and 1161 bp in length, encoding 415, 383, and 386 amino acids, respectively (Fig.1b).TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-Dshared 90.4–92.9% homology at the nucleotide level and 86.1–93.0% homology at the amino acid level.

Cloning of threeTaMYBsm3homologue genes (TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B,andTaMYBsm3-D).a, The amplification ofTaMYBsm3homologue genes;b, The structure ofTaMYBsm3homologue genes. NP6A, NP6B, and NP6D represented three full-length genomic DNA sequences containingTaMYBsm3homologue genes cloned from bacterial artificial chromosomal (BAC) libraries ofTriticum aestivumcultivar Shimai 15. NT-CS representedTaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B,andTaMYBsm3-Dcloned from null-tetrasomic stocks of Chinese Spring

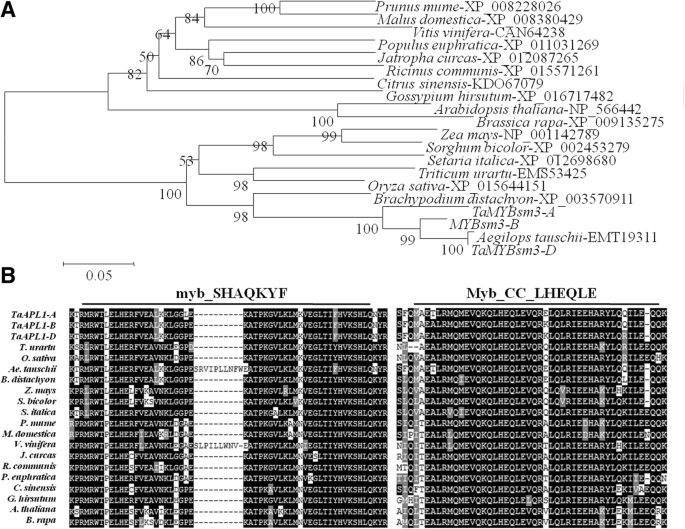

Phylogenetic analysis and multiple alignments of MYBsm3-like proteins

A total of 20 MYBsm3-like proteins isolated from different plants were used for phylogenetic analysis. As shown in Fig.2a, MYBsm3-like proteins were divided into two divergent branches, including monocot and dicot.TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B,andTaMYBsm3-Dwere evolutionarily close toAeMYBsm3inAegilops tauschii(Fig.2a)。Multiple alignments showed that MYBsm3-like proteins contained a highly conserved MYB DNA-binding domain (myb_SHAQKYF) and a highly conserved CC domain (Myb_CC_LHEQLE) (Fig.2b).

Phylogenetic analysis and multiple alignments of 20 MYBsm3-like proteins from different plants.a, Phylogenetic tree;b, Multiple alignments. A highly conserved MYB DNA-binding domain (myb_SHAQKYF) and a highly conserved CC domain (Myb_CC_LHEQLE) were observed in MYBsm3-like proteins. Black shadow represented the conserved residues

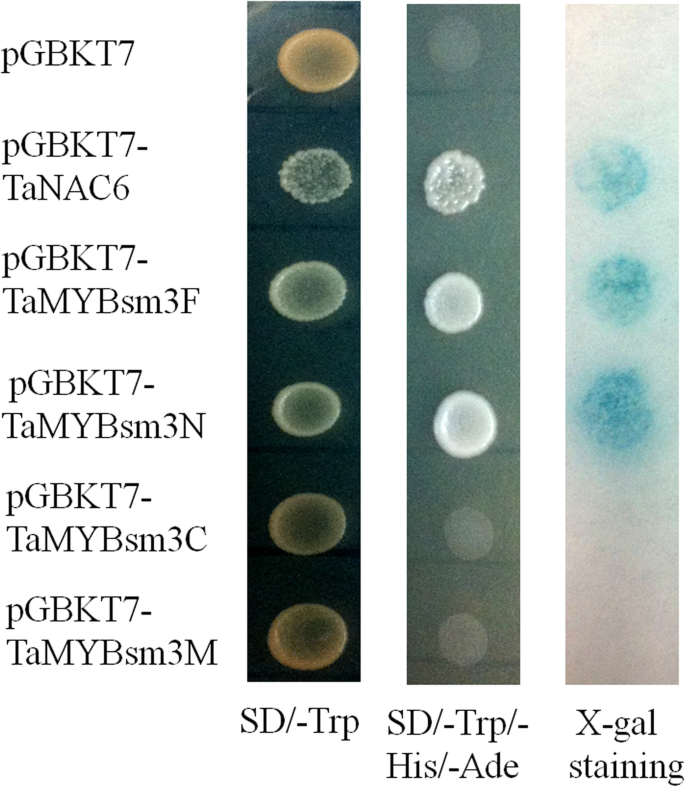

Transcriptional activity and subcellular localization ofTaMYBsm3-D

的转录activity ofTaMYBsm3-Dwas analyzed in yeast. The full-length cDNA (TaMYBsm3F), N-terminal region (TaMYBsm3N), C-terminal region (TaMYB-sm3C), and myb-SHAQKYF region (TaMYBsm3M) were transformed into yeast strain Y190. As shown in Fig.3, the activity of β-galactosidase was found in yeast cells carrying TaMYBsm3F and TaMYBsm3N, but not in yeast cells carrying TaMYBsm3C and TaMYBsm3M (Fig.3). This result indicated that the N-terminal region ofTaMYBsm3was a transcriptional activation domain.

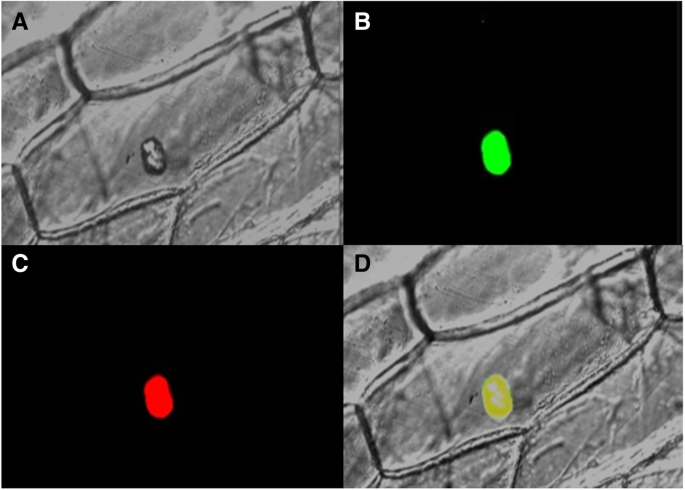

To examine the subcellular localization of TaMYBsm3-D, the full-length cDNA sequence ofTaMYBsm3-Dwas integrated into pCAMBIA1300-sGFP. The fluorescent signal of GFP was found in the nucleus of transformed tobacco epidermal cells. This phenomenon indicated that TaMYBsm3-D was localized in the nucleus (Fig.4).

Expression pattern ofTaMYBsm3homologue genes in wheat

RT-qPCR was used to study the expression pattern of three TaMYBsm3homologue genes in wheat.TaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B,andTaMYBsm3-Dexhibited a consistent expression pattern in wheat. As shown in Fig.5, TaMYBsm3genes were ubiquitously expressed in the root, stem, leaf, stamen, pistil, and seed, and was especially highly expressed in the stamen and pistil. Because of the treatment with 16% PEG8000, the expression of TaMYBsm3genes was significantly increased in the leaf with a peak at 24 h, and in the root with a peak at 3 h (Fig.5).

Overexpression ofTaMYBsm3-Dimproved the drought tolerance of transgenic plants

To reveal the drought tolerance ability ofTaMYBsm3-D,TaMYBsm3-Dwas transformed intoArabidopsis。经过4周的增长在正常情况下,both the WT plants and the transgenic lines (L4, L8, and L13) exhibited normal phenotypes and growth status. After 2 weeks of water deprivation, severe wilting symptoms were observed in the WT, whereas the wilting symptoms were mild in transgenic lines. After 2 days of re-watering, most WT plants died, whereas some transgenic plants recovered to normal growth status (Fig.6a). The germination rates of transgenic plants were higher than that in WT plants under drought stress (P < 0.01) (Fig.6b). The water loss rates were significantly lower in transgenic plants compared with in WT plants under normal conditions (P < 0.05) (Fig.6c). Furthermore, significantly higher proline and lower MDA contents were revealed in transgenic plants compared with that of the WT (P < 0.05) (Fig.6d, e). Taken together, the above results indicated that the drought tolerance of transgenicArabidopsiswas improved by overexpressedTaMYBsm3-D。

Abiotic stress-responsive genes were upregulated inTaMYBsm3-DtransgenicArabidopsis

To reveal the molecular mechanisms related to the drought response ofTaMYBsm3-Dtransgenic plants, the expression levels ofDREB2A,P5CS1, andRD29A(three abiotic stress-responsive genes) were detected. As shown in Fig.7, the expression levels ofDREB2A,P5CS1, andRD29Awere significantly higher in transgenic plants than in WT plants (P < 0.01) (Fig.7). The results indicated thatTaMYBsm3-Dmay enhance the drought tolerance through up-regulating abiotic stress-responsive genes.

Discussion

干旱是一个主要的环境压力,里美ts the productivity of wheat. Searching for novel genes involved in drought tolerance has become a hot topic in breeding [29]. Recently, some MYB-CC genes have been described to be related to Pi availability, but their role in drought stress tolerance of plants has not been reported.

ThePHR1-like genes,TaPHR1genes, were mapped on chromosomes 7A, 4B, 4D and involved in Pi signaling in bread wheat [22]. In this study, threeTaMYBsm3homologue genes with potential drought resistance ability were isolated fromT. aestivumShimai 15 by screening the BAC library. The three genes were mapped on chromosomes 6A, 6B, and 6D in wheat, and namedTaMYBsm3-A,TaMYBsm3-B, andTaMYBsm3-D, respectively.TaPHR1andTaMYBsm3share 32.1–33.7% identity at the nucleotide level and 23.1–26.7% identity at amino acid level, but their two motifs, myb_SHAQKYF and coiled-coil, are highly conserved. The results indicate thatTaPHR1andTaMYBsm3are members of MYB-CC TF family, but they are strongly divergent at the nucleotide and amino acid levels, which may be associated with their diverse functions.

TaMYBsm3belongs to MYB-CC TF, containing a conserved SHAQKYF motifMYB DNA-binding domain at the N-terminal and a conserved CC domain at the C-terminal. The two motifs of plant MYBsm3 homologues exhibited significant conservation and showed no significant difference between dicot and monocot plants [30]. Our further assays showed thatTaMYBsm3-Dwas localized in the nucleus, and presented a transactivation activity of a GAL4-containing reporter gene, indicating the predicted role ofTaMYBsm3-Das a TF. The subcellular localization ofTaMYBsm3-Dwas consistent with most knownMYBgenes from diverse species, such asAtMYB26[31],OsMYB48–1[13],TiMYB2R-1[32], andTaMYB80[33]. The MYB DNA-binding domain at the N-terminal directly contributed to the transcriptional activation ofTaMYBsm3-D.

In this study, the involvement ofTaMYBsm3to drought stress was firstly analyzed by RT-qPCR in wheat. TheTaMYBsm3gene was induced by 16% PEG8000, but presented different expression profiles in leaves and roots of bread wheat. The expression of TaMYBsm3genes was significantly increased in the leaf with a peak at 24 h, while in the root with a peak at 3 h, which indicated thatTaMYBsm3genes were sensitive to drought stress in leaves and roots, and the response of TaMYBsm3was higher in leaves than in roots. Then, the drought resistance ability ofTaMYBsm3-Dwas further evaluated usingTaMYBsm3-DtransgenicArabidopsisplants. The result showed that the transgenic plants exhibited milder wilting symptoms than WT plants under drought stress, and could recover to normal growth status after re-watering. Furthermore, significantly lower water loss rates were observed in transgenic plants comparing with that of WT plants. These phenomena illustrated that the transgenic plants had greater drought tolerance than WT plants. Specially, transgenic plants presented significantly higher germination rates WT plants than WT plants. For most seeds, germination begins with the imbibition of water, which generally included three processes: rapid initial water uptake, a plateau phase with little change in water content, and an increased water content coincident with radicle growth [34]. Although moisture is an important factor that determines the germination rate, there are many other factors that affact the germination rate, such as temperature, oxygen, light, and some intrinsic factors. Thus, the higher germination rate of transgenic plants may be related to other mechanisms. The drought resistance characteristics ofTaMYBsm3-Dare consistent with several known drought resistant MYB genes, such asAtMYB96[35],PbrMYB21[12],OsMYB48–1[13], andTaODORANT1[14].

Proline and MDA are important physiological indicators of drought stress [36,37]. Drought stress can damage the membrane of plant cells and induce the production of active oxygen in plant cells, leading to membrane lipid peroxidation [38]. MDA is known as a biomarker of lipid peroxidation [36]. Furthermore, proline acts as an osmoprotectant in plants subjected to drought stress [39]. In this study, significantly higher proline and lower MDA contents were revealed inTaMYBsm3-D transgenicArabidopsisunder drought stress compared with that of WT plants. These results suggest that the drought resistance ability ofTaMYBsm3-Dis associated with relieved lipid peroxidation and stable osmotic pressure.

Currently, the transcriptional regulatory networks of abiotic stress responses have been deeply studied inArabidopsis。Some stress-responsive genes provide important information regarding the mechanism ofTaMYBsm3-Dinvolved in the drought stress response. In our study,P5CS1,DREB2A, andRD29A, three downstream genes, were upregulated significantly in transgenic plants under drought stress.DREB2Ais TF associated with drought and high-salinity stress responses [40]. It has been reported that up-regulatedDREB2Aenhances drought tolerance by activating stress-inducible genes [41]. InArabidopsis,DREB2Acould be induced by high-salt stress or dehydration (Liu et al., 1998; Nakashima et al., 2000; Sakuma et al., 2002). The up-regulatedDREB2Aenhances the tolerance ofTaMYBsm3-Dtransgenic plants to drought stress by activating stress-induced genes. P5CS is known to be a rate-limiting enzyme in proline biosynthesis, mutations of which result in decreased salt tolerance in transgenic plants (Székely et al., 2008). The overexpression ofP5CSpromotes the drought tolerance of tobacco [42,43], whereas silencing ofP5CS1inhibited the drought tolerance through suppressing proline synthesis and reactive oxygen species accumulation [44]. The accumulation of proline induced byP5CScan enhance the drought tolerance ofTaMYBsm3-Dtransgenic plants. Additionally,RD29Ais important in the ABA-related response to drought through regulating the osmotic potential [45]. Desiccation inducedRD29Awith two-step kinetics, which indicated thatRD29Ahad two or more cis-acting elements, one associated with the ABA-associated response to desiccation, while the other induced by osmotic potential changes (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 1993, Shinozaki and Yamaguchi- Shinozaki, 2007; Hirayama and Shinozaki, 2010). Under drought stress, overexpression ofTaMYBsm3-Dincreased the expression level ofDREB2Ain transgenicArabidopsisand their drought tolerances were enhanced by activating some stress-inducible genes. Due to the upregulation ofP5CS1, proline accumulated inTaMYBsm3transgenicArabidopsis, which increased the drought tolerance of the transgenic plants. In summary, we hypothesize that TaMYBsm3-D may function in drought tolerance through increasing the expression of abiotic stress-responsive genes, includingP5CS1,DREB2A, andRD29A。The present study only analyzed the transcriptional regulation of genes to explain the stress response at protein level. Further study is needed to elucidate the regulation mechanism at translational level. Additionally, functional verification of the effect ofTaMYBsm3genes on drought tolerance is still limited toArabidopsis.Further research on the roles ofTaMYBsm3genes in wheat and regulation mechanisms at the translational level are still needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, theTaMYBsm3genes are MYB-CC type TF genes. Overexpression ofTaMYBsm3-Dimproves the drought tolerance of transgenicArabidopsisthrough up-regulatingP5CS1,DREB2A, andRD29A.

Abbreviations

- BAC:

-

Bacterial artificial chromosomal

- CC:

-

Coiled-coil

- EST:

-

Expressed sequence tags

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- NP:

-

Nested PCR primers

- NRF:

-

Nulliso open reading frame

- NT-CS:

-

Nullisomic tetrasomic line of Chinese Spring

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

- PEG:

-

Polyethylene glycol

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- RT-qPCR:

-

Real-time quantitative PCR

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TFs:

-

Transcription factors

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

- 1.

Xiao W, Vignjevic M, Dong J, Jacobsen S, Wollenweber B. Improved tolerance to drought stress after anthesis due to priming before anthesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) var. Vinjett. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(22):6441.

- 2.

Lenka SK, Katiyar A, Chinnusamy V, Bansal KC. Comparative analysis of drought-responsive transcriptome in Indica rice genotypes with contrasting drought tolerance. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9(3):315.

- 3.

Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(2):221–7.

- 4.

Hussain SS, Kayani MA, Amjad M. Transcription factors as tools to engineer enhanced drought stress tolerance in plants. Biotechnol Prog. 2011;27(2):297.

- 5.

Golldack D, Lüking I, Yang O. Plant tolerance to drought and salinity: stress regulating transcription factors and their functional significance in the cellular transcriptional network. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(8):1383.

- 6.

Zhang L, Zhao G, Xia C, Jia J, Liu X, Kong X. A wheat R2R3-MYB gene, TaMYB30-B, improves drought stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(16):5873–85.

- 7.

Chen Y, Yang X, He K, Liu M, Li J, Gao Z, Lin Z, Zhang Y, Wang X, Qiu X. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the Rice MYB family. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60(1):107–24.

- 8.

Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang CZ, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–10.

- 9.

Antje F, Katja M, Braun EL, Erich G. Evolutionary and comparative analysis of MYB and bHLH plant transcription factors. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2011;66(1):94–116.

- 10.

Dubos C, Stracke R, Grotewold E, Weisshaar B, Martin C, Lepiniec L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(10):573–81.

- 11.

Hichri I, Barrieu F, Bogs J, Kappel C, Delrot S, Lauvergeat V. Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(8):2465.

- 12.

Li K, Xing C, Yao Z, Huang X. PbrMYB21, a novel MYB protein of Pyrus betulaefolia, functions in drought tolerance and modulates polyamine levels by regulating arginine decarboxylase gene. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(9):1186.

- 13.

Xiong H, Li J, Liu P, Duan J, Zhao Y, Guo X, Li Y, Zhang H, Ali J, Li Z. Overexpression of OsMYB48-1 , a novel MYB-related transcription factor, enhances drought and salinity tolerance in Rice. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92913.

- 14.

Wei Q, Luo Q, Wang R, Zhang F, He Y, Zhang Y, Qiu D, Li K, Chang J, Yang G. A wheat R2R3-type MYB transcription factor TaODORANT1 positively regulates drought and salt stress responses in transgenic tobacco plants. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8.

- 15.

Seo P J, Lee S B, Suh M C, et al. The MYB96 transcription factor regulates cuticular wax biosynthesis under drought conditions in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2011;23(3):1138–1152.

- 16.

Zhao Y, Cheng X, Liu X, Wu H, Bi H, Xu H. The wheat MYB transcription factor TaMYB31 is involved in drought stress responses in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1–12.

- 17.

Fujita Y, Fujita M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. ABA-mediated transcriptional regulation in response to osmotic stress in plants. J Plant Res. 2011;124(4):509–25.

- 18.

Seiler C, Harshavardhan VT, Rajesh K, Reddy PS, Strickert M, Rolletschek H, Scholz U, Wobus U, Sreenivasulu N. ABA biosynthesis and degradation contributing to ABA homeostasis during barley seed development under control and terminal drought-stress conditions. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(8):2615–32.

- 19.

Wykoff DD, Grossman AR, Weeks DP, Usuda H, Shimogawara K. Psr1, a nuclear localized protein that regulates phosphorus metabolism in Chlamydomonas. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96(26):15336–41.

- 20.

Xue Y-B, Xiao B-X, Zhu S-N, Mo X-H, Liang C-Y, Tian J, Liao H, Miriam G. GmPHR25, a GmPHR member up-regulated by phosphate starvation, controls phosphate homeostasis in soybean. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(17):4951–67.

- 21.

Ruan W, Guo M, Wu P, Yi K. Phosphate starvation induced OsPHR4 mediates pi-signaling and homeostasis in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2017;93(3):327–40.

- 22.

Wang J, Sun J, Miao J, Guo J, Shi Z, He M, Chen Y, Zhao X, Li B, Han F. A phosphate starvation response regulator Ta-PHR1 is involved in phosphate signalling and increases grain yield in wheat. Ann Bot. 2013;111(6):1139–53.

- 23.

Zhang L, Zhao G, Jia J, Liu X, Kong X. Molecular characterization of 60 isolated wheat MYB genes and analysis of their expression during abiotic stress. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(1):203–14.

- 24.

Meng-jun L, Yu Y, Xin-na G, Xiao G, Ming-qi H, Zhan-liang S, Jin-kao G. Construction and characterization of BAC library from common wheat Shimai15. J Triticeae Crops. 2014;34(2):164–8.

- 25.

Park J, Mi JK, Su JJ, Mi CS. Identification of a novel transcription factor, AtBSD1, containing a BSD domain in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Plant Biol. 2009;52(5):492.

- 26.

Breeden L, Nasmyth K. Regulation of the yeast HO gene. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50(8):643.

- 27.

Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method forAgrobacterium-mediated transformation ofArabidopsis thaliana. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 1998;16(6):735–43.

- 28.

Draper HH, Hadley M. Malondialdehyde determination as index of lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186(186):421.

- 29.

Mohammadi R. Breeding for increased drought tolerance in wheat: a review. Crop and Pasture Science. 2018;69(3):223–241.

- 30.

Rubio V, Linhares F, Solano R, Martín AC, Iglesias J, Leyva A, Paz-Ares J. A conserved MYB transcription factor involved in phosphate starvation signaling both in vascular plants and in unicellular algae. Genes Dev. 2001;15(16):2122–33.

- 31.

Yang C, Xu Z, Song J, Conner K, Vizcay BG, Wilson ZA. Arabidopsis MYB26/MALE STERILE35 regulates secondary thickening in the endothecium and is essential for anther dehiscence. Plant Cell. 2007;19(2):534–48.

- 32.

Liu X, Yang L, Zhou X, Zhou M, Lu Y, Ma L, Ma H, Zhang Z. Transgenic wheat expressing Thinopyrum intermedium MYB transcription factor TiMYB2R-1 shows enhanced resistance to the take-all disease. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(8):2243.

- 33.

Zhao Y, Tian X, Wang F, Zhang L, Xin M, Hu Z, Yao Y, Ni Z, Sun Q, Peng H. Characterization of wheat MYB genes responsive to high temperatures. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17(1):208.

- 34.

Bradford KJ. A water relations analysis of seed germination rates. Plant Physiol. 1990;94(2):840–9.

- 35.

Saetbuyl L, Hyojin K, Ryeojin K, Michung S. Overexpression of Arabidopsis MYB96 confers drought resistance in Camelina sativa via cuticular wax accumulation. Plant Cell Rep. 2014;33(9):1535.

- 36.

Roychoudhury A, Roy C, Sengupta DN. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing the heterologous lea gene Rab16A from rice during high salt and water deficit display enhanced tolerance to salinity stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26(10):1839–59.

- 37.

Zhang L, Zhang L, Xia C, Zhao G, Jia J, Kong X. The novel wheat transcription factor TaNAC47 enhances multiple abiotic stress tolerances in transgenic plants. Front Plant Sci. 2016;6(e109415):1174.

- 38.

Mirzaee M, Moieni A, Ghanati F. Effects of drought stress on the lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities in two canola (Brassica napus L.) cultivars. J Agric Sci Technol. 2013;15(3):593–602.

- 39.

Yamada M, Morishita H, Urano K, Shiozaki N, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Yoshiba Y. Effects of free proline accumulation in petunias under drought stress. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(417):1975–81.

- 40.

Nakashima K, Shinwari ZK, Sakuma Y, Seki M, Miura S, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Organization and expression of two Arabidopsis DREB2 genes encoding DRE-binding proteins involved in dehydration- and high-salinity-responsive gene expression. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42(4):657–65.

- 41.

Sakuma Y, Maruyama K, Osakabe Y, Qin F, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor, DREB2A, involved in drought-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell. 2006;18(5):1292–309.

- 42.

Yamchi A, Jazii FR, Ghobadi C, Mousavi A. Increasing of tolerance to osmotic stresses in tobacco Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi through overexpression of p5cs gene. J Sci Technol Agric Nat Resour. 2005;8(4):31–40.

- 43.

Kishor P, Hong Z, Miao GH, Hu C, Verma D. Overexpression of [delta]-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase increases proline production and confers Osmotolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol. 1995;108(4):1387.

- 44.

Székely G, Abrahám E, Cséplo A, Rigó G, Zsigmond L, Csiszár J, Ayaydin F, Strizhov N, Jásik J, Schmelzer E. Duplicated P5CS genes of Arabidopsis play distinct roles in stress regulation and developmental control of proline biosynthesis. Plant J. 2008;53(1):11.

- 45.

Hirayama T, Shinozaki K. Research on plant abiotic stress responses in the post-genome era: past, present and future. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2010;61(6):1041.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2016YFD0101802, 2017YFD0300408).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

YQ-L and SC-Z contributed to the study design, conducting the study, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. N-Z, WY-Z and MJ-L contributed to the data collection and conducting the study. BH-L and ZL-S contributed to data interpretation and discussion. ZL-S is the guarantor of this work and, as such, has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

作者宣称他们没有参加terests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, N.et al.MYB-CC transcription factor,TaMYBsm3, cloned from wheat is involved in drought tolerance.BMC Plant Biol19,143 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1751-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Keywords

- Drought stress

- TaMYBsm3

- Transcription factor

- Triticum aestivumL

- TaMYBsm3-DtransgenicArabidopsis

- Validation