- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

The differential response of cold-experiencedArabidopsis thalianato larval herbivory benefits an insect generalist, but not a specialist

BMC Plant Biologyvolume19, Article number:338(2019)

Abstract

Background

In native environments plants frequently experience simultaneous or sequential unfavourable abiotic and biotic stresses. The plant’s response to combined stresses is usually not the sum of the individual responses. Here we investigated the impact of cold on plant defense against subsequent herbivory by a generalist and specialist insect.

Results

We determined transcriptional responses ofArabidopsis thalianato low temperature stress (4 °C) and subsequent larval feeding damage by the lepidopteran herbivoresMamestra brassicae(generalist),Pieris brassicae(specialist) or artificial wounding. Furthermore, we compared the performance of larvae feeding upon cold-experienced or untreated plants. Prior experience of cold strongly affected the plant’s transcriptional anti-herbivore and wounding response. Feeding byP. brassicae,M. brassicaeand artificial wounding induced transcriptional changes of 1975, 1695, and 2239 genes, respectively. Of these, 125, 360, and 681 genes were differentially regulated when cold preceded the tissue damage. Overall, prior experience of cold mostly reduced the transcriptional response of genes to damage. The percentage of damage-responsive genes, which showed attenuated transcriptional regulation when cold preceded the tissue damage, was highest inM. brassicaedamaged plants (98%), intermediate in artificially damaged plants (89%), and lowest inP. brassicaedamaged plants (69%). Consistently, the generalistM. brassicaeperformed better on cold-treated than on untreated plants, whereas the performance of the specialistP. brassicaedid not differ.

Conclusions

The transcriptional defense response ofArabidopsisleaves to feeding by herbivorous insects and artificial wounding is attenuated by a prior exposure of the plant to cold. This attenuation correlates with improved performance of the generalist herbivoreM. brassicae, but not the specialistP. brassicae, a herbivore of the same feeding guild.

Background

Plants have evolved a plethora of mechanisms to cope with abiotic or biotic environmental stress (e.g. [1,2,3,4]). Attack by herbivorous insects is a major threat for plants as it can lead to rapid loss of leaf material and thus reduced photosynthetic capacity, often causing severe yield and fitness loss [5,6,7].

Plant defense responses induced by herbivore attack represent a strategy, which is mobilized only on demand [8,9].Inducible defense responses are associated with transcriptional regulation of many genes and shifts in phytohormone levels. Intensively studied key regulators of wounding and herbivore defense responses are the phytohormones jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA) and ethylene (ET), which are the backbone of the plant immune signaling network [10,11,12,13,14,15].Fine-tuning of defense responses to different herbivores is achieved by crosstalk of these signaling pathways and may involve additional plant hormonal regulators like auxins, gibberellins, and brassinosteroids [13,16].

在自然环境中,植物are frequently exposed to simultaneously or consecutively occurring environmental stresses. Combined stresses typically provoke distinct transcriptome reprogramming and plant reactions, which are not simply due to additive effects of the single stresses [17,18,19,20,21,22,23].In case of consecutively occurring environmental stress, plants can “memorize” a past stressful event and benefit from this memory by preparing themselves for a more effective response to upcoming stress. This process has been termed “priming” of a stress response by a past stress experience (reviewed in [24,25,26,27]).

Studies on priming of plant responses to insect herbivory especially focused on herbivore-related priming factors, which reliably indicate future herbivory [28].For example, plant volatiles induced by herbivory and perceived by as yet undamaged plant tissue have been shown to serve as a reliable factor in preparing a plant for improved anti-herbivore defense [29,30.,31,32].Furthermore, insect egg depositions on leaves that indicate upcoming larval herbivory have been shown to prepare a plant for more effective defense against the hatching larvae [30.].Previous exposure of plants to herbivory-induced volatiles or to insect egg depositions are known to alter the transcriptional response to herbivory [33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

So far, only a few recent studies addressed the influence of an herbivory-unrelated, abiotic stress – especially drought – on the plant’s response to subsequent herbivory by including transcriptional and/or metabolic analysis (e.g. [40,41,42]). However, stressful conditions such as cold often precede plant attack by herbivorous insects, which usually need warm temperatures for their activities. A study by Firtzlaff et al. [43] examined how exposure ofArabidopsis thalianato mild cold affects plant defense against later herbivory by the specialistPieris brassicae.The study showed that a significant subset of cold-regulated genes maintained altered transcript levels even after 1 day of deacclimation. Larval feeding, which started 1 day after deacclimation, induced a different transcriptome in the previously cold-exposed than in previously untreated plants and showed a weakened response of defense genes. However, larval performance of the specialistP. brassicaewas similar on cold-experienced and untreated plants [43].These findings are in accordance with some other studies, which also revealed that host plants with attenuated plant defense capacity did not affect the extent of feeding damage inflicted by a specialized herbivorous insect [44] nor the herbivore’s performance [45].

Generalist and specialist herbivorous insects are known to exhibit different tolerances to plant defenses [46].然而,未知是否differentially affected by changes in plant defense that are due to prior exposure of plants to abiotic stress. Here we addressed the questions of whether a generalist insect herbivore shows different sensitivity to cold-mediated changes of feeding-induced host plant defense than a specialist,and if so, which transcriptional differences between cold-treated plants fed on by a generalist or a specialist insect may explain these ecological effects.As in our previous study [43], we used the butterfliesP. brassicaeandMamestra brassicaeand the BrassicaceaA. thalianaas host plant.Pieris brassicaeis specialized on glucosinolate-containing host plants [47], mostly from the Brassicaceae family. Like otherPieridaespecies it possesses highly specific enzymes for detoxification of the glucosinolates [48,49,50], which are typical secondary metabolites of theBrassicales. As generalist, we studiedMamestra brassicae,a moth whose larvae are polyphagous on over 70 plant species in 22 plant families, but exhibit a preference forBrassicacrops [51].In contrast toP. brassicae,M. brassicaedetoxifies glucosinolates by general oxidizing enzymes (reviewed by [52]). Both lepidopteran species are active in Europe from early spring to late autumn [53,54].They may produce two to three generations per season until they hibernate in the soil as pupae. In the natural habitats ofM. brassicaeandP. brassicae, which largely overlap with that ofA. thaliana(GBIF Secretariat: GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Accessed viawww.gbif.org/species/1920506andwww.gbif.org/species/3052436on 01 June 2019), in spring and in autumn a succession of cold days followed by a warm period is common.

In a first approach, we compared performance ofM. brassicaeandP. brassicaeonA. thalianaplants previously exposed to mild cold. We found thatM. brassicaeshowed improved performance on cold-experienced plants, whereasP. brassicaelarval performance was the same on cold-experienced and control plants, thus confirming our previous results with this latter species [43].阐明了转录这些的基础different ecological effects, we compared the transcriptomes of cold-experienced plants exposed to feeding by the specialist, the generalist or to artificial wounding. Including the artificial wounding treatment allowed disentangling insect species-specific effects from wounding effects on the cold stress-reprogrammed plant transcriptome. We found that transcriptional responses of previously cold-exposed plants to specialist feeding, generalist feeding and artificial wounding differed.

Prior cold experience led to differential regulation of 360 M. brassicaefeeding damage-responsive genes. In 98% of these the transcriptional response to feeding damage was attenuated. In contrast, the respective fraction of genes was smaller in artificially wounded (681 genes, 84% with attenuated response) and inP. brassicaefeeding-damaged plants (125 genes, 69% with attenuated response). These transcriptional changes in conjunction with the larval performance data indicate that the generalist benefits from the cold-mediated attenuation of feeding-induced gene de-regulation, whereas the specialist does not.

Results

Generalist and specialist herbivores show different performances on cold-stressed and control plants

We exposedA. thalianaplants to cold (4 °C) for 5 days. After a deacclimation phase (20 °C) of 1 day, larvae of the generalistM. brassicaeand the specialistP. brassicaewere allowed feeding upon the previously cold-experienced plants or on control plants. The weight of these larvae on previously cold-treated (Fig.1: P + TPand P + TM) and untreated (Fig.1: TPand TM) plants and the extent of leaf damage inflicted by the larvae were compared.

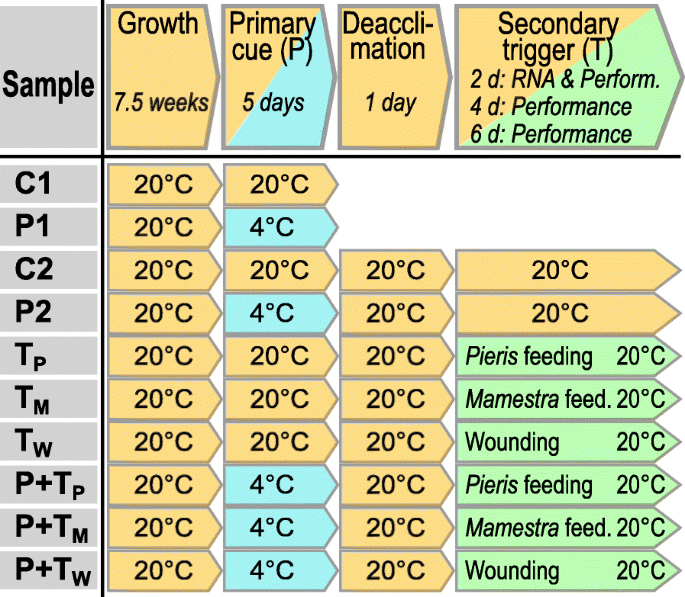

Experimental setup. Seven-week-oldArabidopsis thalianaCol-0 plants were subjected to either cold stress as primary (P) stimulus (4 °C, 5 days) or control (C) conditions (20 °C, 6 days). Plants treated with the primary stimulus were then retransferred to control conditions for 1 day (deacclimation phase). Subsequently plants were treated with a further triggering stimulus (T), i.e. with either larval feeding or artificial wounding. Plants which received both the P and T stimulus are here referred to as P + T plants. Plants, which were not exposed to cold and received only the T stimulus, are labelled as T plants. With respect to the T stimulus, we differentiate between TP(feeding damage byPieris brassicae),TM(feeding damage byMamestra brassicae), and TW(artificial wounding). Untreated control plants (C1, C2) remained at control conditions at 20 °C throughout the entire experiment

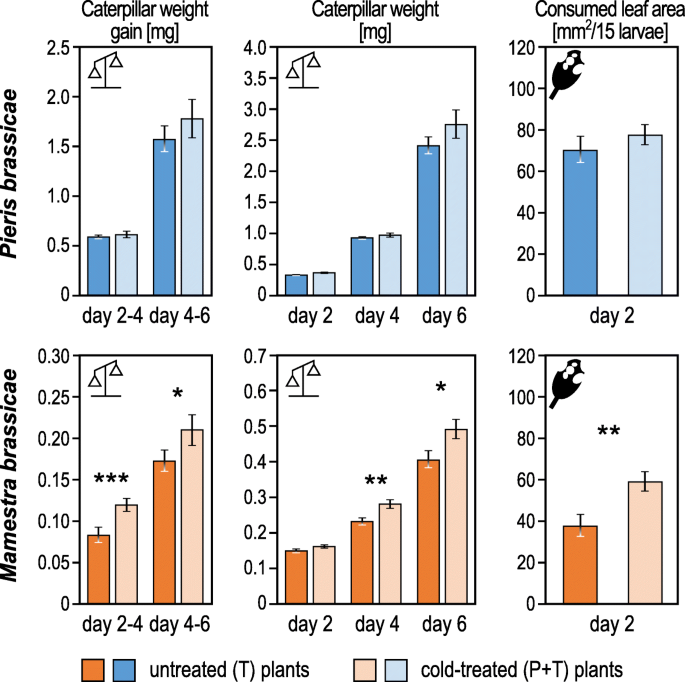

Weight gain and total weight ofP. brassicaelarvae, their leaf area consumption (Fig.2) and the relative growth rate (RGR) of the larvae (Additional file1: Figure S1) did not differ on previously cold-treated compared to untreated plants. In contrast, on previously cold-treated plantsM. brassicaelarvae consumed more leaf tissue, gained more weight and were heavier on these plants after a four- and six-day-feeding period than on untreated plants (Fig.2). Accordingly, the RGR of the larvae was higher on cold-treated plants (Additional file1: Figure S1). This observation suggests that the cold treatment alters either the metabolic status of the plants or their physiological reaction to leaf tissue damage in a way that is beneficial for the larval development of the generalist herbivoreM. brassicae, but without consequences for the development of the specialistP. brassicae.

Performance ofPieris brassicaeandMamestra brassicaeneonate larvae after 2, 4 and 6 days feeding upon previously cold-treated or untreated plants. Larvae were placed onto plants as neonates. Measured parameters (mean values ± SE) are caterpillar weight after 2, 4 and 6 days feeding, weight gain between day 2–4 and day 4–6, and consumed leaf area per plant (each with a group of 15 larvae) after 2 days feeding (from day 0 to day 2). Asterisks indicate significantly different values; *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 as calculated by Student’st-tests.N(P. brassicae): T = 14 plants, P + T = 14 plants;N(M. brassicae): T = 11 plants, P + T = 11 plants

Transcriptional response ofArabidopsisto feeding damage and artificial wounding

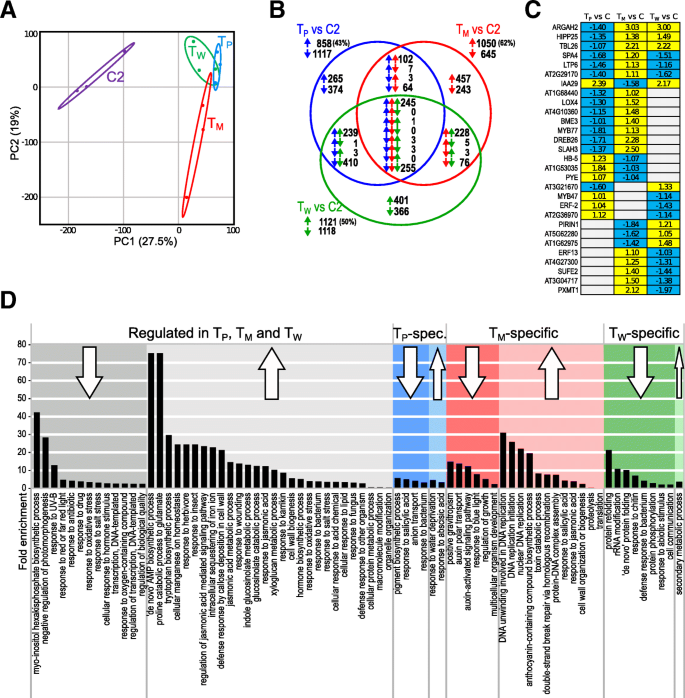

To investigate whetherArabidopsisplants respond differently to leaf damage byP. brassicaeandM. brassicaelarvae and to artificial wounding, we analyzed the transcriptomes in leaves from plants grown at 20 °C (Fig.1, samples TP, TM, TWand C2). A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on gene expression values of the differently treated plants revealed that the patterns of plants exposed toP. brassicaefeeding,M. brassicaefeeding and artificial wounding were clearly separated from untreated control samples. However, the patterns of the treated samples partially overlapped with each other, indicating that expression of a fraction of genes is similarly regulated in the treated samples (Fig.3a).

Regulation of gene expression in response to herbivory or artificial wounding inArabidopsis thalianaleaves compared to untreated control leaves. Plants were exposed to feeding byP. brassicaelarvae (Tp),M. brassicaelarvae (TM), artificial wounding (TW) or were left untreated (C2). Here, the TP, TMand TWtreatments were adjusted in such a way that we obtained comparable extent of leaf damage (about 60 mm2per plant; see Additional file1: Figure S4). Plant material for microarray analysis was collected 2 days later.N= 3 biological replicates of each sample type.aPrinciple component analysis (PCA) of transcriptomic patterns of individual samples collected for microarray analysis. Samples originated from untreated control plants (C2, purple), feeding-damaged plants by eitherP. brassicae(TP, red) orM. brassicae(TM, blue) or artificially wounded plants (TW, green). The first two principal components, which explain most of the changes, are depicted (explained variances are shown at the axes). Ellipses indicate the 95% confidence interval.bThe Venn diagram shows the number of genes, which were upregulated (upwards pointing arrows) or downregulated (downwards pointing arrows) in Tp, TMand TWsamples compared to C2 samples.cHeatmap depicting genes, which show opposed regulation in at least two treatments. Yellow = upregulated, blue = downregulated, grey = not regulated (log2fold changes).dGene Ontology terms associated with commonly or uniquely up- and downregulated genes

Overall, 1975, 1695, and 2239 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified that showed ≥2fold expression change after 2 days feeding damage byP. brassicae(TPvs C2),M. brassicae(TMvs C2) or wounding (TWvs C2), respectively (Fig.3b, Additional file2: Table S1). As the majority of these genes responded qualitatively and quantitatively similarly to the three damage types (Additional file1: Figure S2), the magnitude of the plant’s transcriptional response to herbivory or artificial wounding was similar. However, feeding damage by the generalistM. brassicaeresulted in a larger fraction of upregulated genes (62% of 1695 genes in TMvs C2; Fig.3b) than by the specialistP. brassicae(43% of 1975 genes in TPvs C2, Fig.3b).In total, 507 DEGs were regulated in all three sample types (central intersection in Fig.3b). 176 DEGs specifically responded to larval feeding by either species but not to artificial wounding (Fig.3b; intersection of TPvs C2 and TMvs C2但不是TWvs C2), and 639, 700 and 767 genes were uniquely regulated uponP. brassicaefeeding,M. brassicaefeeding and artificial wounding, respectively. In the intersections, almost all DEGs (94–99%) were regulated in the same direction (Fig.3b).

To disentangle common and unique regulated processes, an enrichment analysis of biological process-Gene Ontology (GO) terms was conducted (Fig.3d). Among the 255 genes downregulated by all three damage types (Fig.3b; central intersection), 13 GO terms were significantly enriched, which associate predominantly with responses to light, transcription, and growth. Among the 245 commonly upregulated genes, 28 GO terms were enriched, including several defense-related processes, such as response to and regulation of jasmonic acid, glucosinolate metabolism and response to insects, herbivores, bacteria, and fungi. These defense-related processes include many well described wounding- and feeding-responsive genes, i.e.JAZ10, VSP1, VSP2, LOX2,CYP79B2,CYP79B3,IGMT1.

Among the DEGs that were specifically responding toP. brassicae-feeding, two GO terms associated with abiotic stress were enriched in the 265 upregulated genes (“response to ABA”, “response to water deprivation”) and four GO terms were enriched in the downregulated genes, including the biological process “response to salicylic acid”.

ManyM. brassicaefeeding-specific upregulated genes fall into GO terms related to transcription and defense, including processes like “DNA replication initiation”, “response to jasmonic acid” and “response to salicylic acid”, whereas the six GO terms overrepresented amongM. brassicae-specific downregulated genes are associated with development and growth.

Artificial wounding-specific responses were overall more generic. Out of 401 upregulated genes only one GO term (“secondary metabolic process”) consisting of 19 genes was weakly enriched. The eight GO terms associated with downregulated genes ranged from protein folding to “defense response to bacterium” to “response to abiotic stress”.

Feeding byP. brassicaeevoked only a weak upregulation of two indole-glucosinolate biosynthesis genes,CYP79B2andCYP79B3, the indole-glucosinolate O-methyltransferasesIGMT1andIGMT5[55,56] and the nitrile specifier geneNSP3(Additional file2: Table S1). Feeding byM. brassicaeinduced a stronger and more complex transcriptional response in the glucosinolate pathway. In addition to theP. brassicae-induced genes,MYB51, NSP1,CYP81F2,CYP81F4andIGMT2were upregulated. Yet, the strongest effects on the glucosinolate system, upregulation of indole-glucosinolate synthesis genes and nitrile specifier protein genes and downregulation of aliphatic glucosinolate synthesis genes, was observed upon artificial wounding of the leaf.

In total, 1648 genes were responsive to at least two damage types. The vast majority of these genes were regulated in the same direction, only 29 genes were regulated in opposite directions (intersections in Fig.3b). The genes with highest regulation differences (15- to 21-fold difference) between at least two treatments wereARGAH2,IAA29,SLAH3,DREB26,andPXMT1(Fig.3c). ARGAH2, one of two arginase proteins known inArabidopsis, is involved in defense responses, as its expression is inducible by methyl jasmonate treatment [57]; this gene was clearly downregulated only byP. brassicaefeeding, but not byM. brassicaedamage nor by artificial wounding.

JA is a major signaling molecule involved in response to wounding and defense against chewing herbivores [58,59,60].Concordantly, artificially wounded leaves showed upregulation of most of the genes involved in JA biosynthesis (i.e.LOX2,AOS,AOC1toAOC4,OPR3), JA homeostasis and turnover (i.e.JAZ2,JAZ9,JA10,IAR3,ILL6,CYP94B3) [61,62,63,64] and JA signaling (i.e.VSP1,VSP2) [58].的JA-responsive defensinPDF1.2a[65] was upregulated as well in artificially wounded leaves. Furthermore, several JA-responsive genes involved in biosynthesis (i.e.CYP81F4,IGMT5) [55,66] and metabolism of glucosinolates (i.e.PYK10,NSP1) [67,68] were upregulated.

Prior cold treatment affects the transcriptional response to tissue damage

To analyze the influence of a preceding cold stress on the transcriptional response to artificial wounding or feeding by a generalist or specialist herbivore, transcriptome analyses of leaf material from plants subjected to the treatments described in the Methods section and in Fig.1were performed.

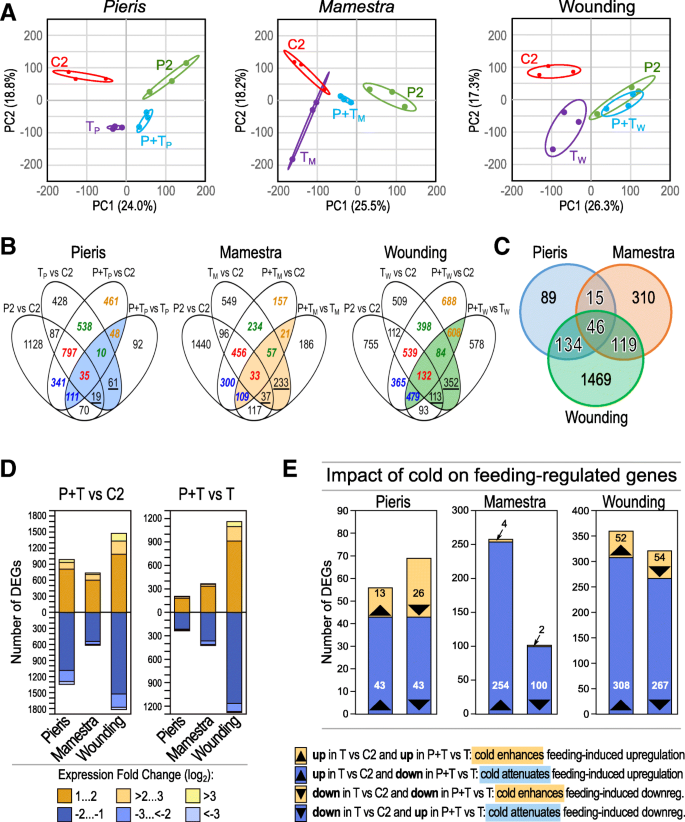

A principle component analysis of gene expression values revealed a clear separation of the C2 control plant transcriptome from that of the other plant treatments, except for the transcriptome ofM. brassicaefeeding-damaged plants (TM), whose 95% confidence interval overlapped slightly with that of the C2 control (Fig.4a). The cold-treated plants (P2) showed a transcriptome shift relative to the C2 control, displayed in the first principle component (PC1), which accounts for ~ 25% of sample variances in all three sample groups. This indicates that deacclimation was not yet completed at the time of sampling. Subsequent feeding damage byP. brassicae(P + TP) orM. brassicae(P + TM) led to a separation of the transcriptome from that of P2 plants, whereas artificial wounding (P + TW) did not. This suggests that a prior cold treatment results in a different plant transcriptional response to continuous two-day-larval feeding damage than to discontinuous artificial wounding. Moreover, the T- and P + T-induced transcriptomes differed also in a species-specific manner, indicating thatArabidopsiscan distinguish between damage byP. brassicaeorM. brassicae(Additional file1: Figure S3).

Previous cold treatment alters the transcriptional response to herbivory and artificial wounding. Leaves ofA. thalianawere untreated (C2), cold-treated (P2), damaged byPieris brassicae(TP) orMamestra brassicaefeeding (TM) or artificial wounding (TW), or cold-treated followed by feeding/wounding damage (P + TP, P + TMand P + TW).N= 3 biological replicates of each sample type.aPrinciple component analysis (PCA) of the normalized gene expression of individual experimental leaf samples. The first two components, which explain most of the changes, are depicted (explained variances are shown at the axes). Ellipses indicate the 95% confidence interval.bVenn diagrams of genes regulated in response to larval feeding or artificial wounding with and without prior cold treatment. Blue characters, genes specifically regulated upon cold treatment; green characters, genes specifically regulated upon damage; red characters, genes regulated upon both cold per se and damage per se; orange characters, genes regulated only when the plant had been exposed to the combination of prior cold and subsequent damage; colored intersections, genes that were differentially regulated in P + T plants relative to T plants (P + T vs T) and also in untreated (T vs C2) or cold-treated, damaged plants (P + T vs C2) relative to control plants.cVenn diagram with the genes in the colored sectors in panel (b).dNumbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in cold-treated and herbivore- or wounding-damaged plants compared to untreated plants (P + T vs C2; left panel) and in cold-treated herbivore- or wounding-damaged plants compared to untreated, damaged plants (P + T vs T; right panel).eGenes responsive to herbivory or artificial wounding with enhanced or attenuated expression changes in cold-treated relative to untreated plants

In cold-treated plants, the total number of regulated genes ranged from 1367 inM. brassicae-damaged leaves to 2341 inP. brassicae-damaged leaves to 3293 in artificially wounded leaves relative to untreated and undamaged control plants (Fig.4b, d; P + T vs C2; the regulated genes are listed in Additional file2: Table S1). Following prior cold stress, 446, 793, and 2439 genes were differentially regulated compared to untreated plants uponP. brassicaeorM. brassicaefeeding or artificial wounding, respectively (Fig.4b, d; P + T vs T). Thus, the total number of genes which were differentially expressed due to prior cold stress was higher in artificially wounded than in larval feeding-damaged plants. In general, roughly equal fractions of DEGs were up- or downregulated in P + TP, P + TM, and P + TWplants compared to the respective T plants.

Of particular interest are those genes that were differentially regulated in cold-treated and damaged plants relative to damaged plants (P + T vs T) and also in untreated and damaged (T vs C2) and/or cold-treated and damaged plants (P + T vs C2) relative to control plants (Fig.4b, colored intersections in Venn diagrams). These gene sets comprise 284, 490, and 1768 genes inP. brassicaefeeding-,M. brassicaefeeding- and wounding-damaged leaves, respectively (Additional file2: Table S1). The 80, 270, and 465 genes in the intersection of T vs C2 and P + T vs T, but not P + T vs C2 (Fig.4b, underlined numbers) were regulated by tissue damage, however, the magnitude of the transcriptional response to damage was diminished when the plants had previously experienced cold. In contrast, genes exclusively occurring in the overlapping intersection of P + T vs T and P + T vs C2 were regulated only upon sequential experience of cold and tissue damage by feeding or wounding, but not by damage of untreated control plants. The intersections of T vs C2, P + T vs T and P + T vs C2 consist of genes that respond to feeding or wounding, and this response was significantly different when plants had been exposed to a prior cold phase.

我们进一步研究了基因是否具体cally or commonly regulated by the three cold / damage combinations. Upon prior cold treatment, 46 DEGs were commonly regulated (40 up, 6 down), i.e. their transcriptional response was independent of the insect species and type of wounding (larval feeding, artificial damage) (Fig.4c, Additional file2: Table S1). Additionally, 15 genes were differentially regulated (7 up, 8 down) after cold exposure and subsequent feeding damage by both herbivore species, but not after cold exposure and subsequent artificial wounding (Fig.4c).

The prior cold treatment also affected the magnitude of the transcriptional response to subsequent tissue damage. InPieris-damaged leaves, the cold pre-treatment caused a significant intensification of damage-induced up- or downregulation in 39 of the 125 damage-induced genes (31%), whereas in the remaining genes the magnitude of regulation was diminished or even turned into opposite regulation (Fig.4e; Additional file2: Table S1). In artificially wounded local leaves, regulation of 84% of the damage-induced genes was attenuated. In leaves damaged byM. brassicae,almost all (98%) feeding-induced genes exhibited attenuated regulation upon prior cold treatment. Only 2% of the feeding-induced genes exhibited intensified expression changes in cold pre-treated plants (Fig.4e). These results show that a cold phase attenuated the transcriptional response to subsequent leaf damage in the majority of damage-induced genes. However, the degree of attenuation was dependent on the type of damage.

Leaf tissue damage affects the cold deacclimation process

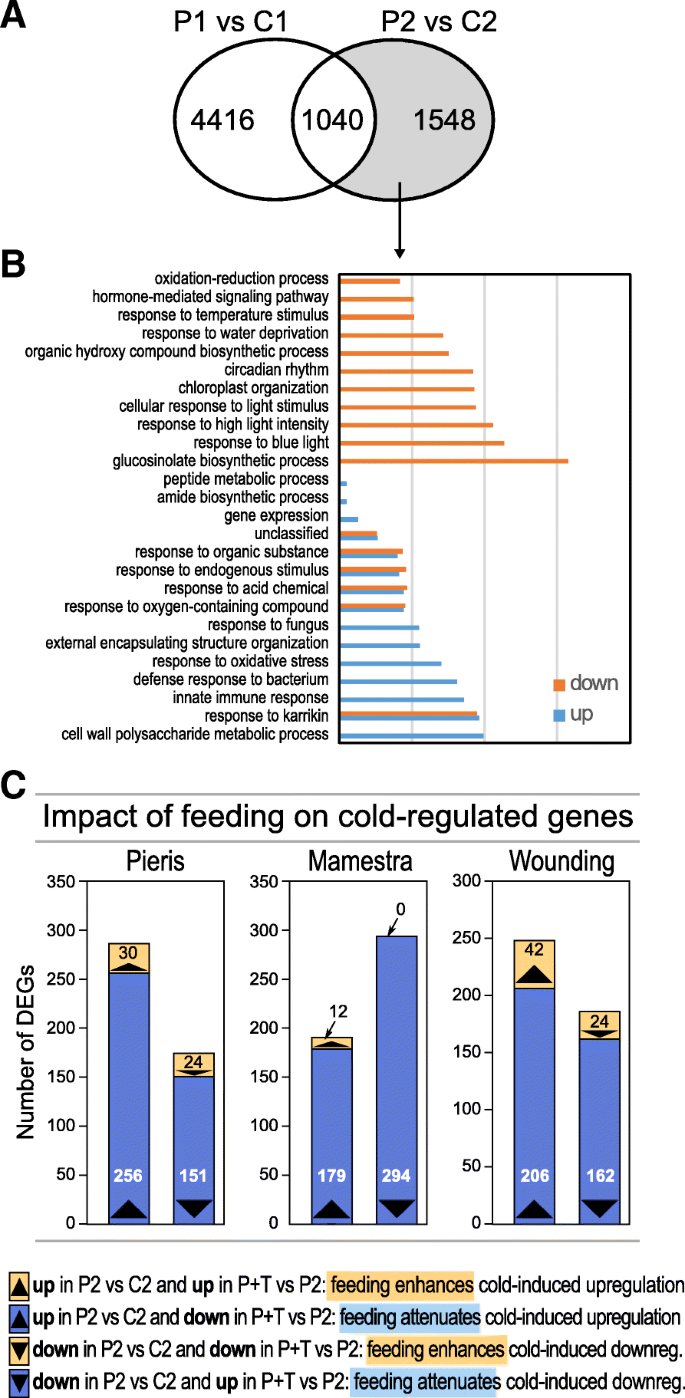

调查是否叶组织损伤的幼虫l feeding and artificial wounding has an impact on gene expression during deacclimation, we compared the transcriptomes of cold-treated plants during deacclimation with or without experience of tissue damage. First, we compared the transcriptome of plants at the end of the cold-period (Fig.1; P1 plants) with that of plants after 3 days of deacclimation (Fig.1; P2 plants). In the P2 plants we found more than 1500 newly regulated genes with 25 significantly enriched biological process GO terms, indicating that deacclimation also involves activation of cellular processes (Fig.5a). Eleven GO terms are enriched only for downregulated genes, nine terms only for upregulated genes, and six terms are enriched for up- and downregulated genes (Fig.5b). Interestingly, the downregulated terms include the ‘glucosinolate biosynthesis process’. A closer look reveals that in this category especially genes with function in aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis were downregulated, likeMAM3,CYP79F1,CYP79F2,SOT18,IPMI1,IPMI2 and CYP83A1.Noticeably, with the exception ofMAM3, none of these genes were differentially regulated after 5 days cold in P1 plants.

Cold deacclimation and impact of larval feeding or artificial wounding on cold-regulated genes.aNumber of uniquely and commonly regulated genes after 5 days cold at 4 °C (P1) and after 3 days of cold deacclimation at 20 °C (P2) in comparison to the untreated controls (C1 and C2).bEnrichment of biological process gene ontology (GO) terms among the P2 vs C2-specifically up- and downregulated genes.cCold-responsive genes with enhanced or attenuated expression changes in leaves exposed to larval feeding or artificial wounding leaves relative to leaves of undamaged plants

It was therefore interesting to investigate how larval feeding or wounding affects this cold deacclimation response, especially with respect to the genes involved in glucosinolate biosynthesis. Overall, the regulation of 14–19% of all 2588 DEGs in deacclimating P2 plants was attenuated when feeding or wounding occurred (Fig.5c, Additional file2: Table S1), resulting in a faster decay of the cold deacclimation response. However, feeding damage byP. brassicaelarvae resulted in higher expression of five of the seven above mentioned aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis genes (MAM3,CYP79F1,CYP79F2,SOT18andIPMI1) in P + TPcompared to deacclimating P2 plants (expression ofIPMI2andCYP83A1is not altered).In contrast, feeding byM. brassicaelarvae increased the expression of only two of the seven genes (IPMI1andCYP79F1). Wounding alone did not increase the transcription level of any of the seven genes.

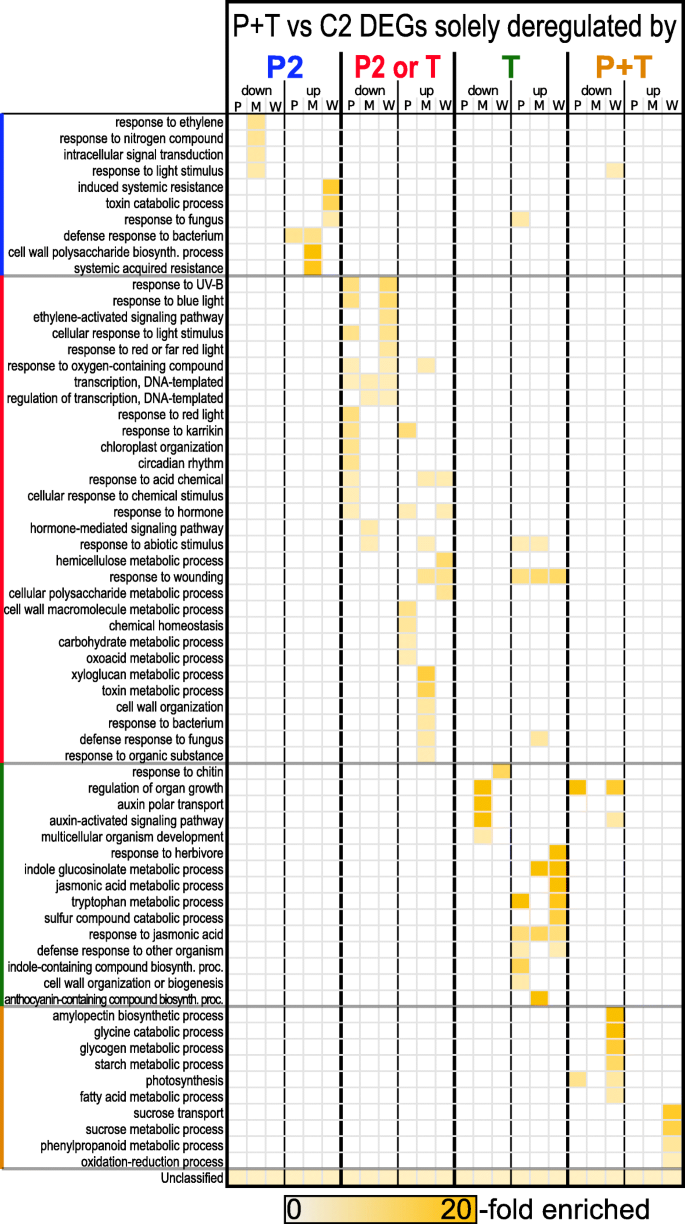

Stress- and stress combination-dependent transcriptional regulation of biological processes

The transcriptome analyses revealed that (i) a preceding cold phase leads to a modified transcriptional response of feeding- or wounding-regulated genes (Fig.4e) and (ii) leaf damage by feeding or wounding modifies the transcription profile of cold-regulated genes during deacclimation (Fig.5c). This raised the question which biological process GO terms contributed to the overall transcriptional status of P + T plants. We thus determined the enriched GO terms (Fig.6) among the genes differentially regulated solely by cold treatment (blue characters in Figs.4band6), by damage (green characters in Figs.4band6), by cold or damage (red characters in Figs.4band6) and by the combination of prior cold and subsequent damage (orange characters in Figs.4band6), respectively. Enhanced gene regulation in many biological process GO terms was triggered almost exclusively by the single stresses cold (P2), damage (T), or the combined stressors cold+damage (P + T). Other GO terms, though, were enriched in cold exposed plants but also after damage (P2 or T). For example, leaf damage exclusively contributed to upregulation of the ‘response to JA’ process. In contrast, in the process ‘response to wounding’ some genes were induced by cold or damage, while other genes were upregulated only by damage.

Treatment-specific enrichment of biological process GO terms of regulated genes in P + T plants. Fold enrichment of biological process GO terms in P + T samples relative to C2 (P + T vs C2) samples of DEG subgroups that are solely deregulated by cold (P2; corresponding to the sectors marked with blue characters in Fig.4b), by either cold or feeding / artificial wounding (P2 or T; corresponding to the sectors marked with red characters in Fig.4b), by larval feeding or artificial wounding (T; corresponding to the sectors marked with green characters in Fig.4b), or only by the combination of cold and larval feeding or artificial damage (P + T; corresponding to the sectors marked with orange characters in Fig.4b)

Of all regulated genes in P + T plants, 13% (Mamestra), 22% (Pieris) and 39% (Wounding) only changed in expression if a cold treatment preceded the tissue damage (Fig.4b, orange characters). These genes can be considered as primable for improved damage-triggered induction by prior cold exposure.

Damage ofA. thalianaleaves byP. brassicae,M. brassicae和人工受伤导致显著的transcriptional changes in 187, 173, and 235 defense- or glucosinolate synthesis-related genes (Additional file2: Table S1). Of these, 30% (Pieris), 43% (Mamestra) and 30% (Wounding) were upregulated. Remarkably, 70% of the defense- or glucosinolate synthesis-related genes upregulated byP. brassicaefeeding were also upregulated byM. brassicaefeeding, whereas 75% of the genes downregulated uponP. brassicaefeeding were not regulated byM. brassicaefeeding. When preceded by cold, the transcriptional response of only 4% of theseP. brassicaefeeding-induced genes was attenuated by ≥2-fold. In contrast, responses of much greater fractions of genes deregulated byM. brassicaefeeding (29%) or wounding (32%) were attenuated by a factor of 2 or more, when the plants had previously been exposed to cold.

Thus, drought or cold stress preceding tissue damage apparently affects similar biological processes ofA. thaliana, but not necessarily the same genes.

Discussion

Similarities and differences inA. thalianatranscriptional response to leaf damage byP. brassicaefeeding,M. brassicaefeeding and artificial wounding

After a prior cold treatment ofArabidopsisplants, larvae of the generalist herbivoreM. brassicaeperformed better than on untreated plants whereas larvae of the specialistP. brassicaedid not benefit, indicating that the cold treatment induced changes in the plant that promoted larval development ofM. brassicae, but not of the specialistP. brassicae. It is conceivable that after a cold phase the plant’s metabolic status or response to differences in leaf tissue damage patterns is altered.

For each of the three leaf damage scenarios approximately two thirds of all regulated genes were also regulated in one or both of the other two damage types. Remarkably, > 98% of these genes were regulated in the same direction, only 29 genes showed opposite regulation upon different damage types (Fig.3b). Several of the genes with the largest regulation differences are known to be involved in plant responses to phytopathogens. For example,argah2mutants show increased susceptibility to pathogens inducing clubroot disease [69,70].SLAH3 is an anion channel expressed in guard cells and involved in stomatal immunity by closure of guard cells in response to pathogen attack [71].DREB26 is responsive to infection by the necrotrophic fungusBotrytis cinereaand to various abiotic stresses as well [72].PXMT1 is a target of miR163, a microRNA which promotes in a light-dependent manner seed germination and primary root length [73] and modulates defense responses against bacterial pathogens [74].The Aux/IAA protein IAA29 is a transcription factor acting as repressor of the auxin signaling pathway [75].

Several studies addressed the hypothesis that highly specialized herbivores are more tolerant towards defenses of their host plants than generalists (reviewed by [46]). However, plant defense responses are multifaceted and not by default more effective against generalists than specialists. Thus, to identify plant responses specifically induced or suppressed by generalist and specialist herbivores, a treatment like artificial wounding can provide a baseline for changes at the molecular level [46,76].Here, 23–30% of genes transcriptionally responding to leaf damage by the specialistP. brassicae, the generalistM. brassicaeor artificial wounding were shared (Fig.3b, central intersection), including upregulation of JA-responsive defense-related genes. This shows that part of the responses to feeding damage overlapped with the reaction to artificial wounding. The majority of wound-responding genes could not be assigned to a distinct, significantly regulated process, indicating a generic “panic” response ofA. thalianato artificial wounding [77].

Artificial wounding resulted in upregulation of many JA biosynthesis genes. Most of these genes were also upregulated to very similar levels in response to feeding byM. brassicaelarvae, whereas transcriptional induction was attenuated or lacking upon feeding byP. brassicaelarvae (Additional file2: Table S1). Interestingly though, many SA-responsive genes are downregulated in response toP. brassicaefeeding. Salicylic acid can act antagonistically to JA-mediated plant defense responses [12,14,60,78], but it can also positively modulate the plant defense against herbivores [35,79].We found that after two days feeding by 10P. brassicaelarvae eight SA-associated WRKY transcription factors are downregulated. The SA-responsive factorsWRKY38,WRKY60andWRKY70are only downregulated uponP. brassicaefeeding, but not uponM. brassicaefeeding or artificial wounding. It will thus be interesting to investigate whetherP. brassicaeoral secretions negatively affect the plant’s SA-response pathway towards a diminished herbivore defense [80,81,82].

Strikingly, opposite toP. brassicaefeeding,M. brassicaefeeding was accompanied by more up- than downregulated SA-response genes, and seven of the eightWRKYgenes downregulated uponP. brassicaefeeding were not responding toM. brassicaefeeding. It is tempting to speculate that, in contrast toP. brassicae,M. brassicaeoral secretions do not dampen the plant’s SA-response pathway. Moreover,M. brassicaefeeding induced inArabidopsisleaves a stronger and more complex transcriptional response of glucosinolate biosynthesis-associated genes. Striking is the upregulation ofMYB51, a regulator of indole glucosinolate biosynthesis [83], the nitrile specifier proteinNSP1[84], the P450 monooxygenasesCYP81F2[85] andCYP81F4[66] and the indole glucosinolate methyltransferaseIGMT2[55].Elevated expression of plant specifier proteins has been found to promoteA. thaliana’s defense againstP. rapaelarvae,a close relative ofP. brassicae,as it detersP. rapaefrom egg deposition on the plants. In addition, the endoparasitoidCotesia rubecula, which prefersP. rapaelarvae as hosts, is more attracted toP. rapae-infested plants overexpressing specifier proteins than toP. rapae-infested Col-0 wild-type plants. In contrast to Col-0, the specifier overexpressors accumulate mainly simple nitriles from glucosinolate hydrolysis [86].CYP81F2encodes a P450 monooxygenase involved in 4MI3G (4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate) synthesis and antifungal defense [85].

Studies of plant interactions with the lepidopteran generalistSpodoptera littoralisand with specialists (includingP. rapaeandP. brassicae) revealed that application of larval oral secretion of these insects results in suppression of plant defense gene expression [87,88].Among the genes with attenuated expression in our study the protease inhibitor DR4 and extracellular lipase 3 EXL3 showed a more pronounced attenuation uponP. brassicaethan uponM. brassicaefeeding (Additional file2: Table S1). These genes are also suppressed upon feeding byS. littoralis[87].It is thus conceivable that the expression attenuation we observed was caused by oral secretions of the herbivores. It is known that plants can distinguish between damage by different herbivores and by artificial wounding [89] because their oral secretions contain species-specific herbivore-associated molecular patterns (HAMPs) that enable plants to modulate their defense responses (reviewed in [90,91,92]). It will be interesting to investigate in the future whether the observed differences between the expression patterns uponP. brassicaeorM. brassicaefeeding depend on such HAMPs.

Prior low temperature exposure causes attenuated regulation of genes responsive to leaf damage

The comparison of expression changes in herbivory- or wounding-responsive genes in plants, which had previously experienced 5 days at 4 °C, revealed similarities, but also striking damage type-dependent differences in transcriptional reprogramming. Among the 46 genes that were regulated after each of the three damage types, several were reported to function in stress responses. The flavonol monooxygenase 1 (FMO1)is known to be essential for the establishment of systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and therefore systemic defenses against pathogens likePseudomonas syringae[93].UGT72E2andUGT72E3are involved in glucosylation of monolignols, which results in increased content of coniferin, syringin, and other phenylpropanoids [94,95,96,97].ALLENE OXIDE CYCLASE1 (AOC1),a key enzyme in JA biosynthesis, is known to be rapidly responding to cold stress ([98,99], reviewed by [100]).

Fifteen genes were differentially regulated only upon leaf damage by either of the two herbivores but not upon artificial wounding. Among the eight commonly downregulated genes is a terpene synthase (TPS03), which is known to be inducible by wounding and herbivory [101].The transcription factorsRAP2.9andZAT10function as regulators in biotic and abiotic stress responses as well as in stress combinations [102,103,104].ORA59is involved in JA/ET synergistic regulation and important for pathogen defense viaPDF1.2activation [15,105].Commonly upregulated genes (7) includeLOX5,a member of the 9-lipoxygenases involved in pathogen defense [106)和PIL1,转录因子坳d- and high light-stress responsive with functions in shade avoidance. It is also JA responsive in a COI-dependent manner [107,108,109].The geneST2Adisplayed increased expression in previously cold-experienced plants responding toP. brassicaefeeding, while the response toM. brassicae是相反的。ST2A 18 sulfotransferases之一Arabidopsis, is involved in JA metabolism by sulfating 11-OH-JA and 12-OH-JA [110].

Common for all three types of tissue damage was that a smaller fraction of damage-responsive genes was more strongly up- or downregulated, whereas in the majority of them the transcriptional response was attenuated after a prior cold treatment. The difference in the fractions of genes with altered regulation betweenP. brassicaeandM. brassicaeis striking, though. In leaves damaged byP. brassicaelarvae 31% of the genes are more intensely and 69% more weakly regulated. In contrast, upon herbivory byM. brassicaelarvae, only 2% of the damage-responsive genes are more intensely regulated whereas in 98% of these genes the expression change is lower than in plants that were not exposed to cold.

Feeding and wounding promote a decline of the cold acclimation status

低温驯化和随后deacclimationknown to be accompanied by extensive transcriptomic and metabolomic reorganization. Not only acclimation but also deacclimation is an active and tightly regulated process, which involves metabolic changes in lipid and cell wall components, downregulation of protein synthesis, and transcriptional reprogramming of jasmonate, brassinosteroid and other hormonal pathways [111,112].Pagter et al. [111] found that the deacclimation-associated responses ofA. thalianaCol-0最快在12 hfter shifting 4 °C-acclimated plants to 20 °C. However, deacclimation is only in part a reversion of cold acclimation, and even after 24 h the plant metabolism and transcriptome have not yet fully reverted to the non-acclimated status [111].It is thus conceivable that after 24 h of deacclimation the plant response to herbivore attack differs from that of untreated plants, but it is not predictable whether the prior cold treatment results in an unspecific or herbivore-specific, improved or compromised defense.

Although the cold deacclimation response is considered to be rapid and mainly passive [112,113], more than 1500 genes were newly regulated 3 days after terminating the plant’s exposure to cold. Similar results were obtained in an earlier study by Firtzlaff et al. [43].Conspicuously, among the newly regulated genes the GO term ‘glucosinolate biosynthesis process’ is downregulated. A weaker expression of these genes could imply a reduced aliphatic glucosinolate content in P2 plants and therefore provide advantageous conditions for the larvae of the generalist herbivore species,M. brassicae.Performance of this generalist species is negatively affected by aliphatic glucosinolates [114,115].In contrast, the specialistP. brassicaeis well known to effectively detoxify glucosinolates (e.g. [48]).

In addition, the differences in the transcriptional response of cold-treatedArabidopsis植物th两食草动物喂养的支持e notion that the generalistM. brassicae, but not the specialistP. brassicae, benefits from a cold phase prior to hatching of the larvae. For instance,AOS(allene oxide synthase), a key gene in JA biosynthesis [116], the antifungal/antimicrobial defense thionin geneTHI2.1[117], and the indolic glucosinolate synthesis genesCYP81F4,CYP81F2andIGMT1[55,66,118] were induced in plants not exposed to cold byM. brassicaefeeding, but not byP. brassicaefeeding. In cold-treated plants, expression of these genes was attenuated uponM. brassicaefeeding, but not altered uponP. brassicaefeeding. This is consistent with the observation that the performance ofP. brassicaelarvae is identical on cold-treated and control plants, whereasM. brassicaelarvae perform better on cold-treated plants. Yet, the plant’s defense response invoked by the feeding damage ofP. brassicaelarvae is comparable in untreated and cold-treatedA. thalianaplants. Since the specialistP. brassicaeis well adapted to the defense measures [119,120] it was expected that its performance is not impaired.

SinceM. brassicaeis more sensitive to the defense compounds ofA. thaliana[114], its performance in untreated plants is negatively affected. In cold-treated plants, though, theM. brassicaefeeding damage pattern elicited an attenuated defense reaction. These results are in accordance with two other studies that addressed the question of how the experience of prior abiotic stress influences later defense responses against herbivores [42,43].Common results of the three studies are: (i) prior exposure of plants to abiotic stress caused a reduced transcriptional induction of tissue damage-inducible defense genes, including attenuated gene expression of e.g. JA- and glucosinolate metabolism-related genes; (ii) the performance of the specialist herbivoresP. rapae[42] andP. brassicae(this study and [43]) was not affected by prior drought or cold treatment ofA. thaliana; (iii) herbivory led to a shift from the drought- or cold-adapted transcriptome towards herbivore defense, thus accelerating the abiotic stress deacclimation. Yet, the differentially regulated genes in feeding-damaged plants with prior drought or cold experience differed to a great extent. Only two genes, a glutathione S-transferase (GSTU8) andUPF0496是反式criptionally responding to all tissue damage types when preceded by drought or cold.

Conclusions

We show that a prior cold treatment ofA. thalianadifferentially reprogrammed the transcriptional response to leaf tissue damage by artificial wounding and feeding by the specialist herbivoreP. brassicaeor the generalist herbivoreM. brassicae. The cold-treatment resulted at the transcriptional level in an attenuation of the plant’s damage-induced defense response. We suggest that this attenuation is responsible for the improved larval performance of the generalistM. brassicae. In contrast, the specialistP. brassicaeis unaffected by the damage-inducedA. thalianadefense measures and accordingly does not benefit from the defense attenuation by a preceding cold treatment of the plants.

Methods

Plant growth

Arabidopsis thalianaColumbia Col-0 seeds (Stock No. N1093) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC). Seeds were sown on soil type A (2:2:1, Einheitserde CL P: Einheitserde CL T: Sand) and stratified for 2 days at 4 °C. Thereafter, plants were grown in a growth chamber at short day conditions (8 h/16 h light/dark cycle, 120μE), 20 °C and 50% relative humidity for 7 weeks. Three-week-old seedlings were transplanted in pots containing soil type B (7:7:3, Einheitserde CL P: Einheitserde CL T: Perlite).

Insect rearing

Pieris brassicaelarvae from in-house captive breeding were reared on savoy cabbage (Brassica oleraceaconvar.Capitatavar.sabauda) as described by [43].Mamestra brassicaewere obtained from N. Fatouros (Biosystematics Group, Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, Netherlands). Larvae were reared on cabbage plants (Brassica oleraceavar.sabellicaL.) until pupation. Soil was provided to last instarM. brassicaelarvae for pupation, whileP. brassicaepupae were kept on cardboard. Adults ofM. brassicaewere offered water and a sugar-water solution (1:5 w/v). AdultP. brassicaebutterflies were fed with an aqueous honey solution.

Plant treatments

The experimental design is depicted in Fig.1. Seven-week-old plants were subjected to (i) 5 days cold at 4 °C (P samples), (ii) leaf damage byP. brassicaelarvae (TPsamples),M. brassicaelarvae (TMsamples) or artificial wounding (TWsamples), (iii) cold followed by leaf damage (P + TP, P + TMor P + TW样本)或(iv)没有刺激(C样品)。的性病mulus ‘cold’ was applied for 5 days, followed by 1 day under normal growth conditions (20 °C) as memory/deacclimation phase. P1 samples were taken directly after 5 days of cold and P2 samples 3 days after transferring plants back to 20 °C (Fig.1). The second stress (larval herbivory or artificial wounding) was applied for 2 days following the 1 day memory/deacclimation phase. For treatment with larvae, neonateP. brassicaeorM. brassicaelarvae were added in a clipcage to leaf number 17. For control, an empty clipcage was placed on leaf number 17 of untreated control (C) and cold-pretreated (P) plants. Artificial wounding was applied by damaging leaf number 17 with forceps for 30 s two times a day for 2 days. The damaged area almost matched the area of damage that larvae feeding inside a clipcage inflicted to a leaf.

Larval performance measurement

Individual seven-week-old plants treated with or without prior cold were subjected to feeding by 15 freshly hatchedM. brassicaeorP. brassicaelarvae on leaf 17. The experiments were repeated 11 times (N= 11 plants) withM. brassicaeand 15 times (N= 15 plants) withP. brassicae. Larvae were confined in clipcages with a diameter of 3 cm. Two days later, larval weight and weight gain were determined. Furthermore, the consumed leaf area was assessed by comparing pictures of the leaves taken before and after 2 days feeding using ImageJ [121].The leaf expansion during the 2 days feeding period was marginal and not taken into account. Subsequently larvae were returned to the plants and allowed to feed upon the whole plant for another 4 days. Two and 4 days later larval weight and weight gain were measured again. Larval performance data were evaluated with “R” [122] and subjected to statistical analysis [123,124].Data were tested for normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogenous variances (Levene’s test). If larval weight and weight gain values were not normally distributed and/or did not show variance homogeneity, data were log2transformed to fulfil the prerequisites for applying unpaired Student’st-test.

Transcriptome analyses

We analyzed the transcriptome of untreated plants (C), cold-exposed plants (P), damaged plants (T) and cold-exposed and feeding-damaged plants (P + T). We standardized the extent of damage by insects and artificial wounding to be able to ascribe damage-induced transcriptomic changes to the type of damage rather than to the extent of damage. Therefore, plant leaves were exposed to 10P. brassicaelarvae or 20 M. brassicaelarvae in a clip cage. After 2 days feeding, the leaf area consumed by the two species was almost identical (Additional file1: Figure S4). The artificially wounded area was similar as well. For RNA extraction, a 1 cm wide strip from leaf number 17 of C1, C2, P1, P2, TP, TM, TW, P + TP, P + TMand P + TWplants was harvested. The stripe was located proximal to the clipcage or wounding site. To minimize effects of circadian clock-dependent transcriptional regulation, all samples were collected 4 to 6 h after the onset of the daylight phase, i.e. at a time when larvae are actively feeding in nature. After harvesting, the strips were kept frozen in liquid nitrogen. Leaf material of three individual plants was pooled to obtain one biological replicate, and three biological replicates of each sample type were analyzed.

Frozen leaf material was ground in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted according to Onate-Sanchez [125].Total RNA was DNase I-digested according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Yield and quality of extracted RNA was determined spectrophotometrically and by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis.

Genome-wide expression analyses were conducted on ArrayXS Arabidopsis v2 microarrays (series XS-5010; GEO accession GPL19779; Oaklabs GmbH, Hennigsdorf, Germany). Microarray data were processed and analyzed with theBioconductor Linear Modelsfor microarray data (limma) software package [126,127] as described in Firtzlaff et al. [43].In short, microarray signals were background-corrected and interarray-normalized. Genes with ≥2-fold expression change and adjustedP-values ≤0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate procedure) were defined to be differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Additional file1: Figure S2). Gene expression data are deposited in the NCBI GEO repository under the accession number GSE114211.

Principle component analysis (PCA) of the transcriptomic data sets was performed using the “ggplot” and “ggbiplot” packages of “R” [122,128].Enriched gene ontology (GO) terms were identified using theTAIR GO Term Enrichment for Plantstool (www.arabidopsis.org) provided by PANTHER DB (http://pantherdb.org). If not mentioned otherwise, a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was applied to reduce false positives.

Availability of data and materials

Microarray transcription raw data are deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under the accession number GSE114211.

Abbreviations

- ABA:

-

Abscisic acid

- DEG:

-

Differentially expressed gene

- ET:

-

Ethylene

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- JA:

-

Jasmonic acid

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- SA:

-

Salicylic acid

References

- 1.

Walling LL. The myriad plant responses to herbivores. J Plant Growth Regul. 2000;19(2):195–216.

- 2.

Hirayama T, Shinozaki K. Research on plant abiotic stress responses in the post-genome era: past, present and future. Plant J. 2010;61(6):1041–52.

- 3.

Baxter A, Mittler R, Suzuki N. ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(5):1229–40.

- 4.

Zebelo SA, Maffei ME. Role of early signalling events in plant-insect interactions. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(2):435–48.

- 5.

Nabity PD, Zavala JA, DeLucia EH. Indirect suppression of photosynthesis on individual leaves by arthropod herbivory. Ann Bot. 2009;103(4):655–63.

- 6.

Núñez-Farfán J, Fornoni J, Valverde PL. The evolution of resistance and tolerance to herbivores. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S. 2007;38:541–66.

- 7.

Strauss SY, Rudgers JA, Lau JA, Irwin RE. Direct and ecological costs of resistance to herbivory. Trends Ecol Evol. 2002;17(6):278–85.

- 8.

Schaller A. Induced plant resistance to herbivory. Stuttgart: Springer; 2008.

- 9.

Karban R, Baldwin IT. Induced responses to herbivory. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1997. 330 p.

- 10.

Howe GA, Jander G. Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:41–66.

- 11.

Koo AJ, Howe GA. The wound hormone jasmonate. Phytochemistry. 2009;70(13–14):1571–80.

- 12.

Pieterse CM, Leon-Reyes A, Van der Ent S, Van Wees SC. Networking by small-molecule hormones in plant immunity. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(5):308–16.

- 13.

Verhage A, van Wees SC, Pieterse CM. Plant immunity: it's the hormones talking, but what do they say? Plant Physiol. 2010;154(2):536–40.

- 14.

Pieterse CM, Van der Does D, Zamioudis C, Leon-Reyes A, Van Wees SC. Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:489–521.

- 15.

Wasternack C, Hause B. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in annals of botany. Ann Bot. 2013;111(6):1021–58.

- 16.

Diezel C, von Dahl CC, Gaquerel E, Baldwin IT. Different lepidopteran elicitors account for cross-talk in herbivory-induced phytohormone signaling. Plant Physiol. 2009;150(3):1576–86.

- 17.

Mittler R. Abiotic stress, the field environment and stress combination. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11(1):15–9.

- 18.

Prasch CM, Sonnewald U. Signaling events in plants: stress factors in combination change the picture. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;114:4–14.

- 19.

Stam JM, Kroes A, Li Y, Gols R, van Loon JJ, Poelman EH, et al. Plant interactions with multiple insect herbivores: from community to genes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:689–713.

- 20.

Atkinson NJ, Urwin PE. The interaction of plant biotic and abiotic stresses: from genes to the field. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(10):3523–43.

- 21.

Ramegowda V, Senthil-Kumar M. The interactive effects of simultaneous biotic and abiotic stresses on plants: mechanistic understanding from drought and pathogen combination. J Plant Physiol. 2015;176:47–54.

- 22.

Suzuki N, Rivero RM, Shulaev V, Blumwald E, Mittler R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol. 2014;203(1):32–43.

- 23.

Voelckel C, Baldwin IT. Herbivore-induced plant vaccination. Part II. Array-studies reveal the transience of herbivore-specific transcriptional imprints and a distinct imprint from stress combinations. Plant J. 2004;38(4):650–63.

- 24.

Hilker M, Schwachtje J, Baier M, Balazadeh S, Bäurle I, Geiselhardt S, et al. Priming and memory of stress responses in organisms lacking a nervous system. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2016;91(4):1118–33.

- 25.

Conrath U, Beckers GJ, Langenbach CJ, Jaskiewicz MR. Priming for enhanced defense. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2015;53:97–119.

- 26.

Martinez-Medina A, Flors V, Heil M, Mauch-Mani B, Pieterse CM, Pozo MJ, et al. Recognizing plant defense priming. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21(10):818–22.

- 27.

Pastor V, Luna E, Mauch-Mani B, Ton J, Flors V. Primed plants do not forget. Environ Exp Bot. 2013;94:46–56.

- 28.

Mescher MC, De Moraes CM. Plant biology: pass the ammunition. Nature. 2014;510(7504):221–2.

- 29.

Heil M, Ton J. Long-distance signalling in plant defence. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13(6):264–72.

- 30..

Hilker M, Fatouros NE. Plant responses to insect egg deposition. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:493–515.

- 31.

Hilker M, Fatouros NE. Resisting the onset of herbivore attack: plants perceive and respond to insect eggs. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;32:9–16.

- 32.

Karban R, Yang LH, Edwards KF. Volatile communication between plants that affects herbivory: a meta-analysis. Ecol Lett. 2014;17(1):44–52.

- 33.

Altmann S, Muino JM, Lortzing V, Brandt R, Himmelbach A, Altschmied L, et al. Transcriptomic basis for reinforcement of elm antiherbivore defence mediated by insect egg deposition. Mol Ecol. 2018;27(23):4901–15.

- 34.

Geuss D, Stelzer S, Lortzing T, Steppuhn A.Solanum dulcamara's response to eggs of an insect herbivore comprises ovicidal hydrogen peroxide production. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40(11):2663–77.

- 35.

Lortzing V, Oberländer J, Lortzing T, Tohge T, Steppuhn A, Kunze R, et al. Insect egg deposition renders plant defence against hatching larvae more effective in a salicylic acid-dependent manner. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42:1019–32.

- 36.

Büchel K, McDowell E, Nelson W, Descour A, Gershenzon J, Hilker M, et al. An elm EST database for identifying leaf beetle egg-induced defense genes. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:242.

- 37.

Engelberth J, Contreras CF, Dalvi C, Li T, Engelberth M. Early transcriptome analyses of Z-3-hexenol-treatedZea maysrevealed distinct transcriptional networks and anti-herbivore defense potential of green leaf volatiles. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77465.

- 38.

Ton J, D'Alessandro M, Jourdie V, Jakab G, Karlen D, Held M, et al. Priming by airborne signals boosts direct and indirect resistance in maize. Plant J. 2007;49(1):16–26.

- 39.

Bonnet C, Lassueur S, Ponzio C, Gols R, Dicke M, Reymond P. Combined biotic stresses trigger similar transcriptomic responses but contrasting resistance against a chewing herbivore inBrassica nigra. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17(1):127.

- 40.

Coolen S, Proietti S, Hickman R, Davila Olivas NH, Huang PP, Van Verk MC, et al. Transcriptome dynamics of Arabidopsis during sequential biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant J. 2016;86(3):249–67.

- 41.

Weldegergis BT, Zhu F, Poelman EH, Dicke M. Drought stress affects plant metabolites and herbivore preference but not host location by its parasitoids. Oecologia. 2015;177(3):701–13.

- 42.

Davila Olivas NH, Coolen S, Huang P, Severing E, van Verk MC, Hickman R, et al. Effect of prior drought and pathogen stress onArabidopsistranscriptome changes to caterpillar herbivory. New Phytol. 2016;210(4):1344–56.

- 43.

Firtzlaff V, Oberländer J, Geiselhardt S, Hilker M, Kunze R. Pre-exposure ofArabidopsisto the abiotic or biotic environmental stimuli "chilling" or "insect eggs" exhibits different transcriptomic responses to herbivory. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28544.

- 44.

Stotz HU, Pittendrigh BR, Kroymann J, Weniger K, Fritsche J, Bauke A, et al. Induced plant defense responses against chewing insects. Ethylene signaling reduces resistance of Arabidopsis against Egyptian cotton worm but not diamondback moth. Plant Physiol. 2000;124(3):1007–18.

- 45.

Müller R, de Vos M, Sun JY, Sønderby IE, Halkier BA, Wittstock U, et al. Differential effects of indole and aliphatic glucosinolates on lepidopteran herbivores. J Chem Ecol. 2010;36(8):905–13.

- 46.

Ali JG, Agrawal AA. Specialist versus generalist insect herbivores and plant defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(5):293–302.

- 47.

Feltwell J. The large white butterfly: the biology, biochemistry and physiology ofPieris brassicae(Linnaeus). The Hague: Dr. W. Junk Publishers; 1982.

- 48.

Wittstock U, Agerbirk N, Stauber EJ, Olsen CE, Hippler M, Mitchell-Olds T, et al. Successful herbivore attack due to metabolic diversion of a plant chemical defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(14):4859–64.

- 49.

Kumar R, Bhardwaj U, Kumar P, Mazumdar-Leighton S. Midgut serine proteases and alternative host plant utilization in Pieris brassicae L. Front Physiol. 2015;6:95.

- 50.

Stauber EJ, Kuczka P, van Ohlen M, Vogt B, Janowitz T, Piotrowski M, et al. Turning the 'mustard oil bomb' into a 'cyanide bomb': aromatic glucosinolate metabolism in a specialist insect herbivore. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35545.

- 51.

Rojas JC, Wyatt TD, Birch MC. Flight and oviposition behavior toward different host plant species by the cabbage moth,Mamestra brassicae(L.) (Lepidoptera : Noctuidae). J Insect Behav. 2000;13(2):247–54.

- 52.

Hopkins RJ, van Dam NM, van Loon JJ. Role of glucosinolates in insect-plant relationships and multitrophic interactions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2009;54:57–83.

- 53.

Grüner C, Sauer KP. Aestival dormancy in the cabbage moth Mamestra brassicae L. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) : 1. Adaptive significance of variability of two traits: Day length thresholds triggering aestival dormancy and duration of aestival dormancy. Oecologia. 1988;74(4):515–23.

- 54.

Held C, Spieth HR. First evidence of pupal summer diapause in Pieris brassicae L.: the evolution of local adaptedness. J Insect Physiol. 1999;45(6):587–98.

- 55.

Pfalz M, Mikkelsen MD, Bednarek P, Olsen CE, Halkier BA, Kroymann J. Metabolic engineering inNicotiana benthamianareveals key enzyme functions in Arabidopsis indole glucosinolate modification. Plant Cell. 2011;23(2):716–29.

- 56.

Pfalz M, Mukhaimar M, Perreau F, Kirk J, Hansen CI, Olsen CE, et al. Methyl transfer in glucosinolate biosynthesis mediated by indole glucosinolate O-methyltransferase 5. Plant Physiol. 2016;172(4):2190–203.

- 57.

Brownfield DL, Todd CD, Deyholos MK. Analysis ofArabidopsisarginase gene transcription patterns indicates specific biological functions for recently diverged paralogs. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;67(4):429–40.

- 58.

Zhang L, Zhang F, Melotto M, Yao J, He SY. Jasmonate signaling and manipulation by pathogens and insects. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(6):1371–85.

- 59.

Campos ML, Kang JH, Howe GA. Jasmonate-triggered plant immunity. J Chem Ecol. 2014;40(7):657–75.

- 60.

Erb M, Meldau S, Howe GA. Role of phytohormones in insect-specific plant reactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(5):250–9.

- 61.

Widemann E, Miesch L, Lugan R, Holder E, Heinrich C, Aubert Y, et al. The amidohydrolases IAR3 and ILL6 contribute to jasmonoyl-isoleucine hormone turnover and generate 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid upon wounding in Arabidopsis leaves. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(44):31701–14.

- 62.

Heitz T, Widemann E, Lugan R, Miesch L,乌尔曼P,Desaubry L, et al. Cytochromes P450 CYP94C1 and CYP94B3 catalyze two successive oxidation steps of plant hormone jasmonoyl-isoleucine for catabolic turnover. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(9):6296–306.

- 63.

Kitaoka N, Matsubara T, Sato M, Takahashi K, Wakuta S, Kawaide H, et al. Arabidopsis CYP94B3 encodes jasmonyl-L-isoleucine 12-hydroxylase, a key enzyme in the oxidative catabolism of jasmonate. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52(10):1757–65.

- 64.

Koo AJ, Cooke TF, Howe GA. Cytochrome P450 CYP94B3 mediates catabolism and inactivation of the plant hormone jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(22):9298–303.

- 65.

Penninckx IA, Thomma BP, Buchala A, Metraux JP, Broekaert WF. Concomitant activation of jasmonate and ethylene response pathways is required for induction of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10(12):2103–13.

- 66.

Kai K, Takahashi H, Saga H, Ogawa T, Kanaya S, Ohta D. Metabolomic characterization of the possible involvement of a cytochrome P450, CYP81F4, in the biosynthesis of indolic glucosinolate in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnology. 2011;28(4):379–85.

- 67.

Nakano RT, Pislewska-Bednarek M, Yamada K, Edger PP, Miyahara M, Kondo M, et al. PYK10 myrosinase reveals a functional coordination between endoplasmic reticulum bodies and glucosinolates inArabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2017;89(2):204–20.

- 68.

Wittstock U, Meier K, Dorr F, Ravindran BM. NSP-dependent simple nitrile formation dominates upon breakdown of major aliphatic glucosinolates in roots, seeds, and seedlings ofArabidopsis thalianaColumbia-0. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1821.

- 69.

Gravot A, Deleu C, Wagner G, Lariagon C, Lugan R, Todd C, et al. Arginase induction represses gall development during clubroot infection in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53(5):901–11.

- 70.

Brauc S, De Vooght E, Claeys M, Geuns JM, Hofte M, Angenon G. Overexpression of arginase inArabidopsis thalianainfluences defence responses againstBotrytis cinerea. Plant Biol (Stuttg). 2012;14(Suppl 1):39–45.

- 71.

Zheng X, Kang S, Jing Y, Ren Z, Li L, Zhou JM, et al. Danger-associated peptides close stomata by OST1-independent activation of anion channels in guard cells. Plant Cell. 2018;30(5):1132–46.

- 72.

Sham A, Moustafa K, Al-Ameri S, Al-Azzawi A, Iratni R, AbuQamar S. Identification ofArabidopsiscandidate genes in response to biotic and abiotic stresses using comparative microarrays. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125666.

- 73.

Chung PJ, Park BS, Wang H, Liu J, Jang IC, Chua NH. Light-inducible miR163 targets PXMT1 transcripts to promote seed germination and primary root elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016;170(3):1772–82.

- 74.

Chow HT, Ng DW. Regulation of miR163 and its targets in defense againstPseudomonas syringaeinArabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46433.

- 75.

Liscum E, Reed JW. Genetics of aux/IAA and ARF action in plant growth and development. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49(3–4):387–400.

- 76.

Lortzing T, Firtzlaff V, Nguyen D, Rieu I, Stelzer S, Schad M, et al. Transcriptomic responses of Solanum dulcamara to natural and simulated herbivory. Mol Ecol Resour. 2017;17(6):e196–211.

- 77.

Avramova Z. The jasmonic acid-signalling and abscisic acid-signalling pathways cross talk during one, but not repeated, dehydration stress: a non-specific 'panicky' or a meaningful response? Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40(9):1704–10.

- 78.

Thaler JS, Humphrey PT, Whiteman NK. Evolution of jasmonate and salicylate signal crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(5):260–70.

- 79.

Rostas M, Winter TR, Borkowski L, Zeier J. Copper and herbivory lead to priming and synergism in phytohormones and plant volatiles in the absence of salicylate-jasmonate antagonism. Plant Signal Behav. 2013;8(6):e24264.

- 80.

Chung SH, Rosa C, Scully ED, Peiffer M, Tooker JF, Hoover K, et al. Herbivore exploits orally secreted bacteria to suppress plant defenses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(39):15728–33.

- 81.

Acevedo FE, Smith P, Peiffer M, Helms A, Tooker J, Felton GW. Phytohormones in fall armyworm saliva modulate defense responses in plants. J Chem Ecol. 2019;https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-019-01079-z.

- 82.

Mason CJ, Jones AG, Felton GW. Co-option of microbial associates by insects and their impact on plant-folivore interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42(3):1078–86.

- 83.

Gigolashvili T, Berger B, Mock HP, Müller C, Weisshaar B, Flügge UI. The transcription factor HIG1/MYB51 regulates indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis inArabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;50(5):886–901.

- 84.

Burow M, Losansky A, Muller R, Plock A, Kliebenstein DJ, Wittstock U. The genetic basis of constitutive and herbivore-induced ESP-independent nitrile formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;149(1):561–74.

- 85.

Bednarek P, Pislewska-Bednarek M, Svatos A, Schneider B, Doubsky J, Mansurova M, et al. A glucosinolate metabolism pathway in living plant cells mediates broad-spectrum antifungal defense. Science. 2009;323(5910):101–6.

- 86.

Mumm R, Burow M, Bukovinszkine'kiss G, Kazantzidou E, Wittstock U, Dicke M, et al. Formation of simple nitriles upon glucosinolate hydrolysis affects direct and indirect defense against the specialist herbivore,Pieris rapae. J Chem Ecol. 2008;34(10):1311–21.

- 87.

Consales F, Schweizer F, Erb M, Gouhier-Darimont C, Bodenhausen N, Bruessow F, et al. Insect oral secretions suppress wound-induced responses inArabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(2):727–37.

- 88.

Reymond P, Bodenhausen N, Van Poecke RM, Krishnamurthy V, Dicke M, Farmer EE. A conserved transcript pattern in response to a specialist and a generalist herbivore. Plant Cell. 2004;16(11):3132–47.

- 89.

Shinya T, Hojo Y, Desaki Y, Christeller JT, Okada K, Shibuya N, et al. Modulation of plant defense responses to herbivores by simultaneous recognition of different herbivore-associated elicitors in rice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32537.

- 90.

Mithöfer A, Boland W. Recognition of herbivory-associated molecular patterns. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(3):825–31.

- 91.

Maffei ME, Arimura G, Mithofer A. Natural elicitors, effectors and modulators of plant responses. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29(11):1288–303.

- 92.

Basu S, Varsani S, Louis J. Altering plant defenses: herbivore-associated molecular patterns and effector arsenal of chewing herbivores. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018;31(1):13–21.

- 93.

Mishina TE, Zeier J. The Arabidopsis flavin-dependent monooxygenase FMO1 is an essential component of biologically induced systemic acquired resistance. Plant Physiol. 2006;141(4):1666–75.

- 94.

König S, Feussner K, Kaever A, Landesfeind M, Thurow C, Karlovsky P, et al. Soluble phenylpropanoids are involved in the defense response of Arabidopsis againstVerticillium longisporum. New Phytol. 2014;202(3):823–37.

- 95.

Lanot A, Hodge D, Jackson RG, George GL, Elias L, Lim EK, et al. The glucosyltransferase UGT72E2 is responsible for monolignol 4-O-glucoside production inArabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2006;48(2):286–95.

- 96.

Miao YC, Liu CJ. ATP-binding cassette-like transporters are involved in the transport of lignin precursors across plasma and vacuolar membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(52):22728–33.

- 97.

Zhao Q, Nakashima J, Chen F, Yin Y, Fu C, Yun J, et al. Laccase is necessary and nonredundant with peroxidase for lignin polymerization during vascular development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):3976–87.

- 98.

Hannah MA, Heyer AG, Hincha DK. A global survey of gene regulation during cold acclimation inArabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(2):e26.

- 99.

Hu Y, Jiang L, Wang F, Yu D. Jasmonate regulates the INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION-C-REPEAT BINDING FACTOR/DRE BINDING FACTOR1 cascade and freezing tolerance inArabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25(8):2907–24.

- 100.

Kazan K. Diverse roles of jasmonates and ethylene in abiotic stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20(4):219–29.

- 101.

Huang M, Abel C, Sohrabi R, Petri J, Haupt I, Cosimano J, et al. Variation of herbivore-induced volatile terpenes among Arabidopsis ecotypes depends on allelic differences and subcellular targeting of two terpene synthases, TPS02 and TPS03. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(3):1293–310.

- 102.

金Mittler R, Y,歌L CoutuJ, Coutu A, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, et al. Gain- and loss-of-function mutations in Zat10 enhance the tolerance of plants to abiotic stress. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(28–29):6537–42.

- 103.

Prasch CM, Sonnewald U. Simultaneous application of heat, drought, and virus to Arabidopsis plants reveals significant shifts in signaling networks. Plant Physiol. 2013;162(4):1849–66.

- 104.

Tsutsui T, Kato W, Asada Y, Sako K, Sato T, Sonoda Y, et al. DEAR1, a transcriptional repressor of DREB protein that mediates plant defense and freezing stress responses in Arabidopsis. J Plant Res. 2009;122(6):633–43.

- 105.

Pre M, Atallah M, Champion A, De Vos M, Pieterse CM, Memelink J. The AP2/ERF domain transcription factor ORA59 integrates jasmonic acid and ethylene signals in plant defense. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(3):1347–57.

- 106.

Vicente J, Cascon T, Vicedo B, Garcia-Agustin P, Hamberg M, Castresana C. Role of 9-lipoxygenase and alpha-dioxygenase oxylipin pathways as modulators of local and systemic defense. Mol Plant. 2012;5(4):914–28.

- 107.

Ciolfi A, Sessa G, Sassi M, Possenti M, Salvucci S, Carabelli M, et al. Dynamics of the shade-avoidance response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013;163(1):331–53.

- 108.

Rasmussen S, Barah P, Suarez-Rodriguez MC, Bressendorff S, Friis P, Costantino P, et al. Transcriptome responses to combinations of stresses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013;161(4):1783–94.

- 109.

Robson F, Okamoto H, Patrick E, Harris SR, Wasternack C, Brearley C, et al. Jasmonate and phytochrome a signaling in Arabidopsis wound and shade responses are integrated through JAZ1 stability. Plant Cell. 2010;22(4):1143–60.

- 110.

Gidda SK, Miersch O, Levitin A, Schmidt J, Wasternack C, Varin L. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a hydroxyjasmonate sulfotransferase fromArabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(20):17895–900.

- 111.

Pagter M, Alpers J, Erban A, Kopka J, Zuther E, Hincha DK. Rapid transcriptional and metabolic regulation of the deacclimation process in cold acclimatedArabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):731.

- 112.

Zuther E, Juszczak I, Lee YP, Baier M, Hincha DK. Time-dependent deacclimation after cold acclimation inArabidopsis thalianaaccessions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12199.

- 113.

Byun YJ, Koo MY, Joo HJ, Ha-Lee YM, Lee DH. Comparative analysis of gene expression under cold acclimation, deacclimation and reacclimation in Arabidopsis. Physiol Plantarum. 2014;152(2):256–74.

- 114.

Beekwilder J, van Leeuwen W, van Dam NM, Bertossi M, Grandi V, Mizzi L, et al. The impact of the absence of aliphatic glucosinolates on insect herbivory in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2008;3(4):e2068.

- 115.

Jeschke V, Kearney EE, Schramm K, Kunert G, Shekhov A, Gershenzon J, et al. How glucosinolates affect generalist lepidopteran larvae: growth, development and glucosinolate metabolism. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1995.

- 116.

Schaller F. Enzymes of the biosynthesis of octadecanoid-derived signalling molecules. J Exp Bot. 2001;52(354):11–23.

- 117.

Epple P, Apel K, Bohlmann H. Overexpression of an endogenous thionin enhances resistance of Arabidopsis againstFusarium oxysporum. Plant Cell. 1997;9(4):509–20.

- 118.

Pfalz M, Vogel H, Kroymann J. The gene controlling the indole glucosinolate modifier1 quantitative trait locus alters indole glucosinolate structures and aphid resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21(3):985–99.

- 119.

Smallegange RC, van Loon JJ, Blatt SE, Harvey JA, Agerbirk N, Dicke M. Flower vs. leaf feeding byPieris brassicae: glucosinolate-rich flower tissues are preferred and sustain higher growth rate. J Chem Ecol. 2007;33(10):1831–44.

- 120.

Schweizer F, Heidel-Fischer H, Vogel H, Reymond P. Arabidopsis glucosinolates trigger a contrasting transcriptomic response in a generalist and a specialist herbivore. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;85:21–31.

- 121.

Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):671–5.

- 122.

R Development Core Team. R : A language and environment for statistical computing. ed. Vienna University of Economics and Business. Vienna: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. Retrieved fromhttp://www.R-project.org.

- 123.

Revelle W. Psych: procedures for personality and psychological research. Evanston: Northwestern University; 2018.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych. Version = 1.8.12.

- 124.

Fox J, Weisberg S. An R companion to applied Regression, Third Edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2019.https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/.

- 125.

Onate-Sanchez L, Vicente-Carbajosa J. DNA-free RNA isolation protocols forArabidopsis thaliana, including seeds and siliques. BMC Res Notes. 2008;1:93.

- 126.

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al.limmapowers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47.

- 127.

史密斯星期。线性模型和经验贝叶斯方法s for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3(1):Article3.

- 128.

Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Gentleman R, Hornik K, Parmigiani G, editors. New York: Springer; 2009. 213 p.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nina Fatouros for providingMamestra brassicae, Charlotte Thomas for general lab support and the members of the Hilker and Kunze labs for valuable discussions.

Funding

The research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Collaborative Research Centre 973, project B4 (www.sfb973.de). The funding body was not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions